Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

The Larkin Tower

Nearly all proposals for the tallest building in the world include some type of defining element or design flourish that make them unique and memorable. The Chrysler Building has its metallic crown. The Empire State Building has it’s mooring mast and antenna. Not the Larkin Building. It was designed in 1926 for a site on 42nd Street on Manhattan, and it was 368 meters (1,207 feet) tall, making it the tallest structure in the world by a long shot. Aside from this, there’s not much else to say about it.

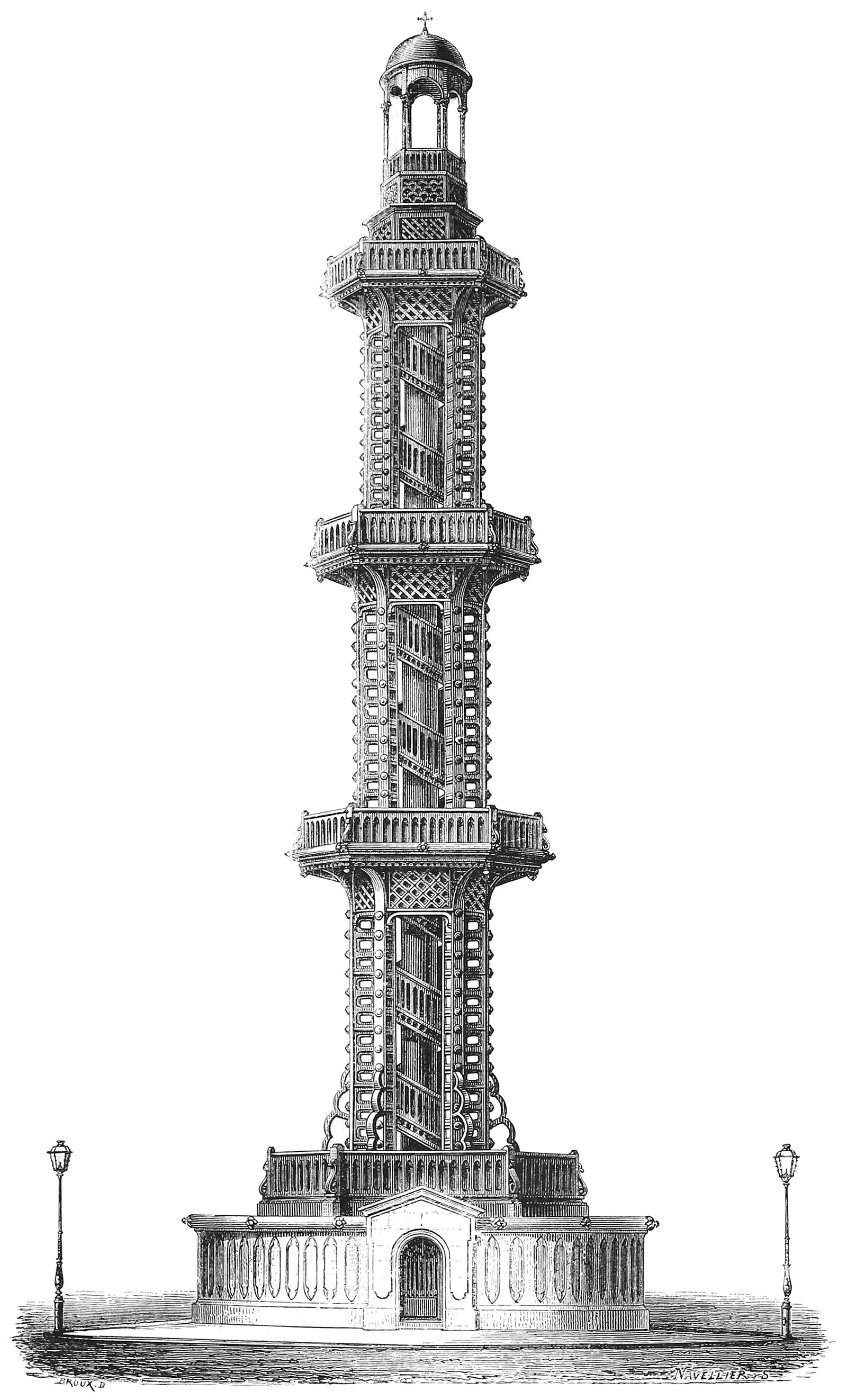

The Towering Centerpiece of an International World Centre

Pictured above is a monumental tower designed by Ernest Hébrard as part of a design for an international world centre. It was a visionary project without a real location, and I suspect it was either academic, or he designed it in order to make a name for himself as an architect and an artist. Either way, this tower was the centerpiece of a much larger plan, but it speaks volumes about Hébrard’s intent with the plan.

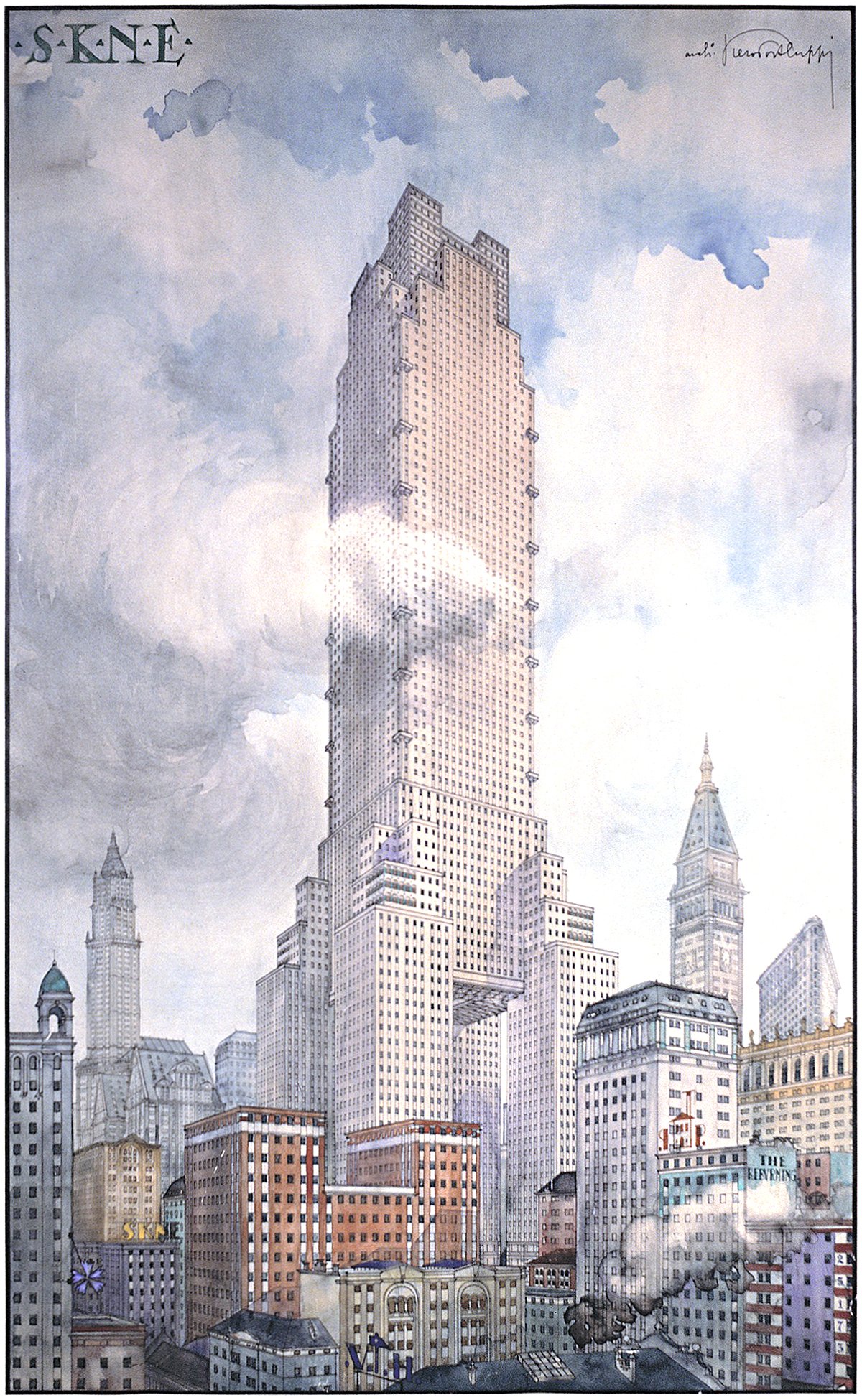

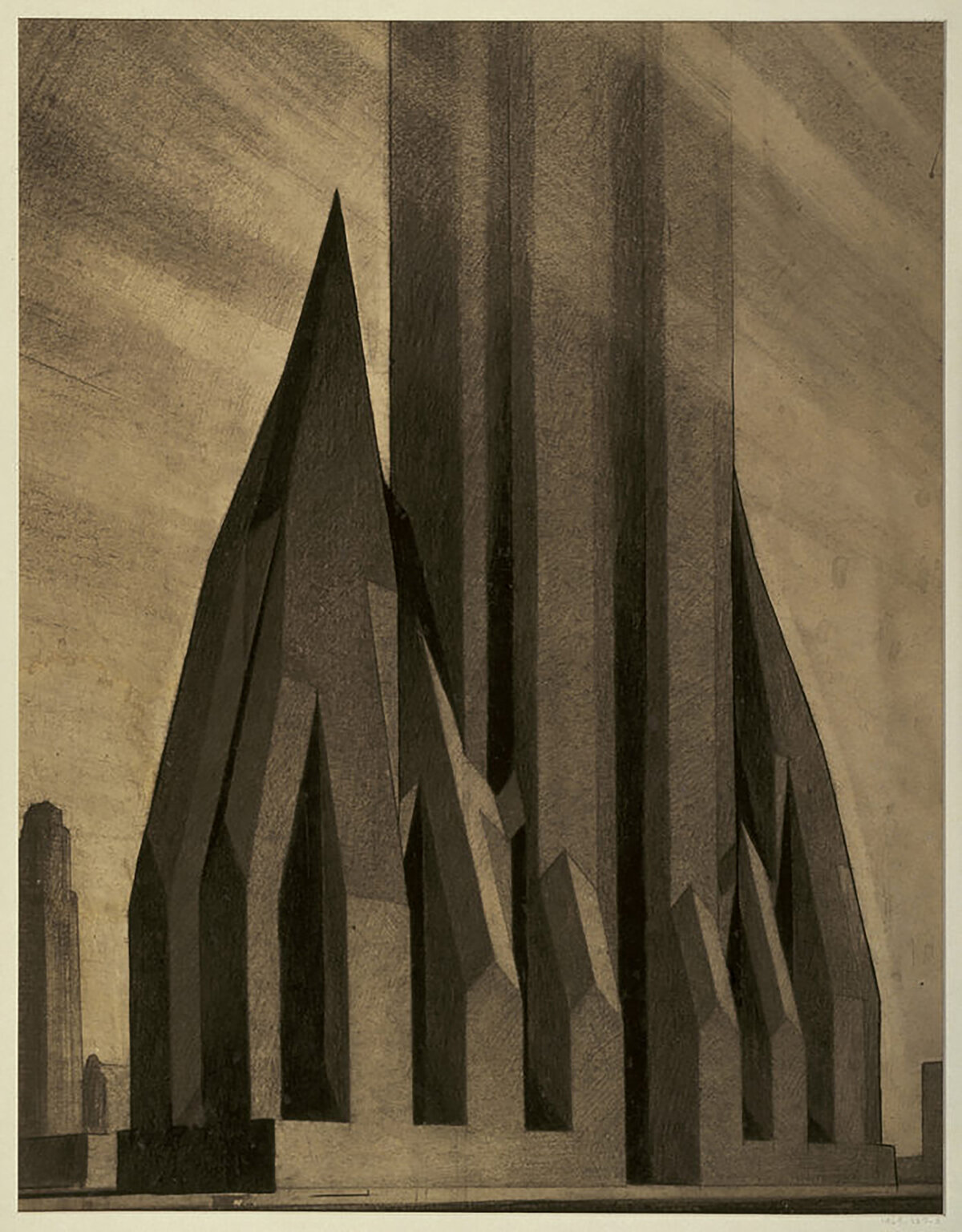

Piero Portaluppi’s SKNE Company Skyscraper

Pictured above is a conceptual design for a skyscraper by Piero Portaluppi from 1920. It was designed as the headquarters of the SKNE company for a site somewhere in New York. There’s two interesting angles here. The first is the tower itself, and the second is the method of representation shown.

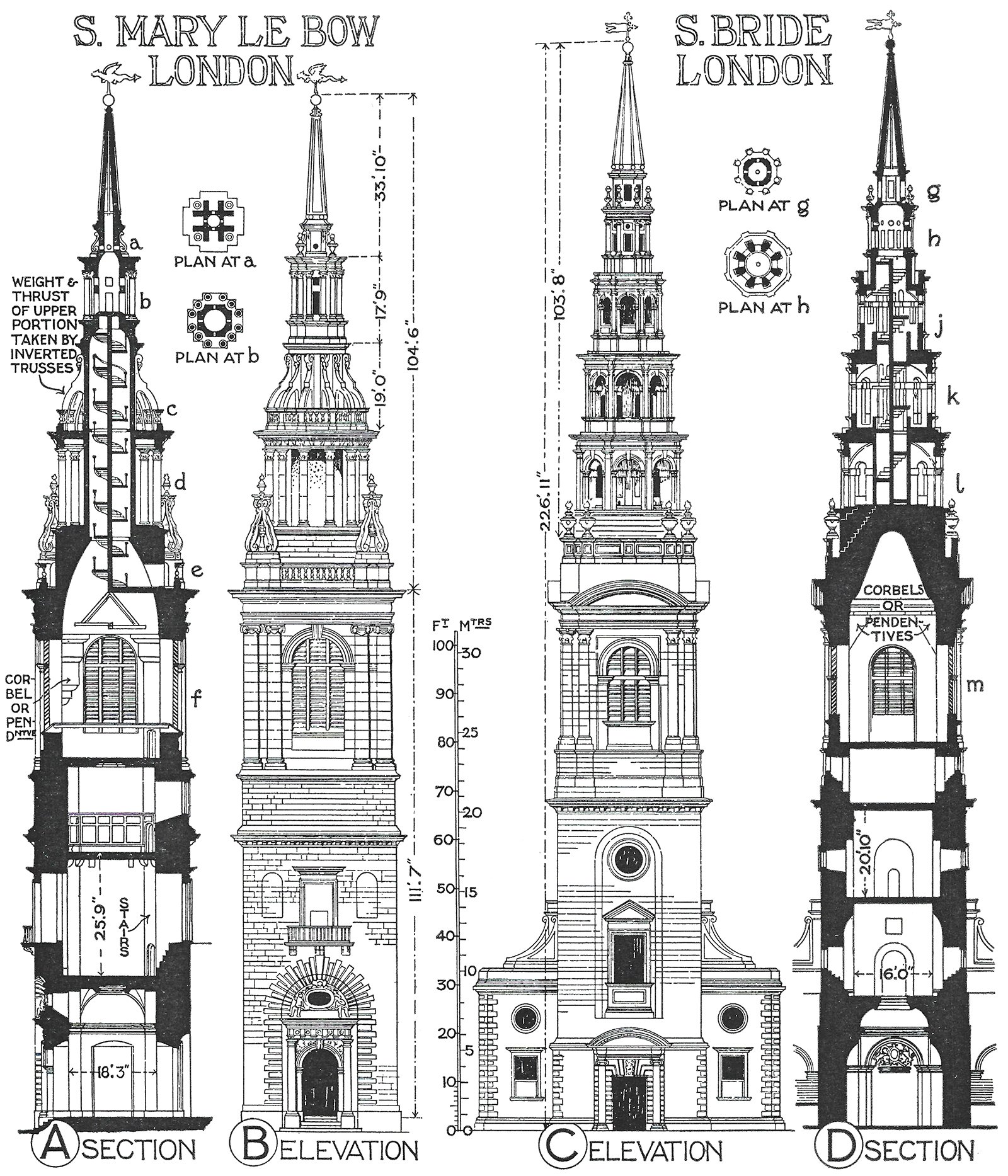

Sir Christopher Wren’s Church Steeples

Sir Christopher Wren was an English architect best known for his Renaissance and Baroque church designs that commonly featured conspicuous steeple designs. Pictured above are drawings of two such examples. These steeples are massive in scale, and they dwarf their adjacent church buildings. This mismatch of scales suggests that Wren considered these towers to be much more important than the churches they accompany. Through their height, Wren was using verticality to announce the presence of his buildings.

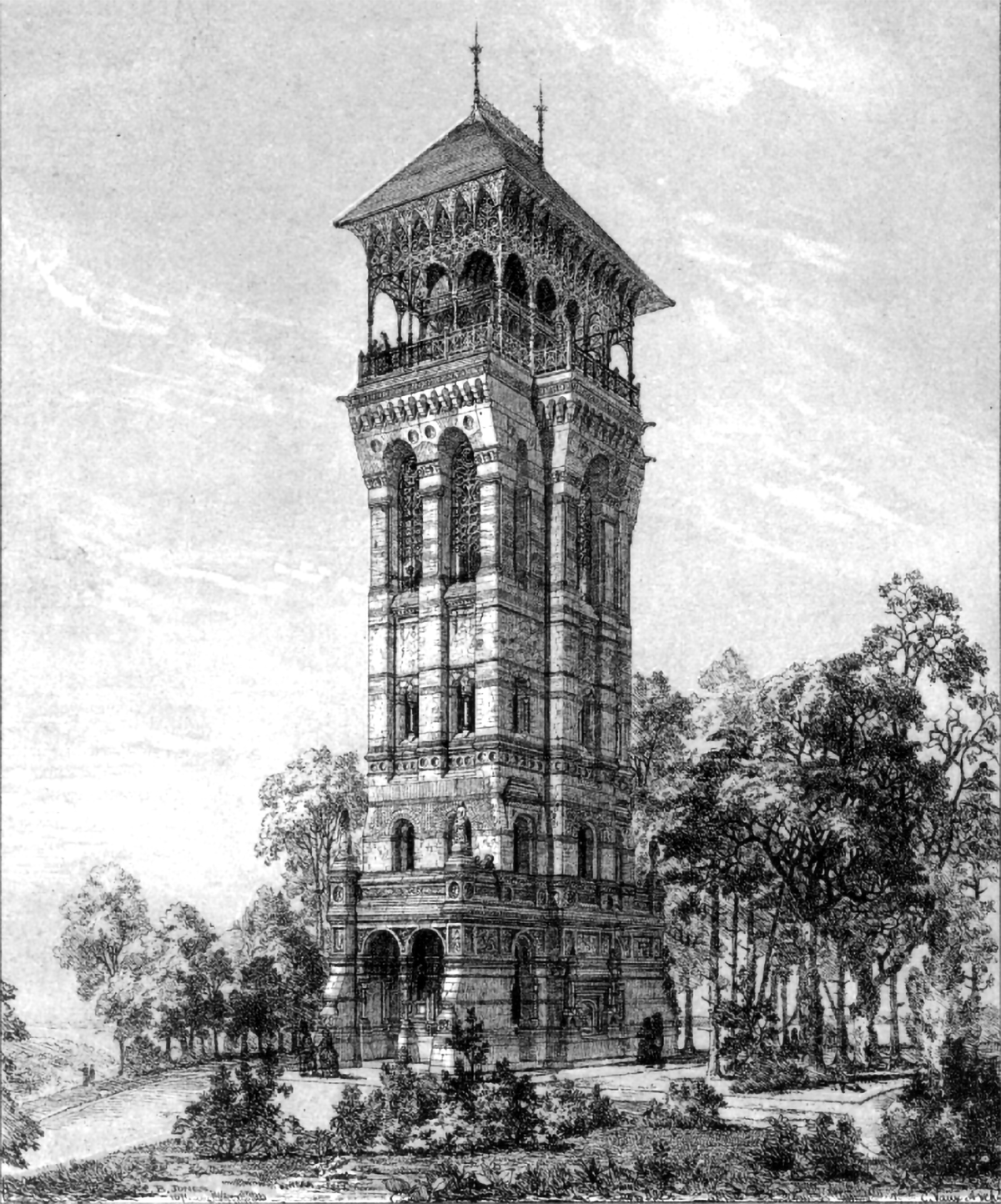

A Proposal for an Observation Tower in Prospect Park

Prospect Park in Brooklyn is one of the great examples of landscape architecture in the United States. It was designed by the legendary landscape architects Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux and was completed between 1867 and 1873. The original design included an observation tower at the highest point in the park, which is pictured above. Unfortunately, it never got built.

The Towers of Svaneti

Joseph Campbell once said that you can tell what’s informing a society by what the tallest building is. The Towers of Svanetia are a perfect example of this. Svanetia is a mountainous region in Georgia dotted with small, medieval villages. These highland villages are home to a unique type of tower house, which gives us a window into the history and culture of the region. Pictured above is an illustration of one such village and its towers.

The Grenelle Artesian Well of Paris

Pictured above is the Grenelle Artesian Well in Paris, built from 1834 to 1841. During these seven years, an 8-inch diameter hole was drilled to a depth of roughly 550 meters (1,800 feet) below the earth’s surface. This process of construction took place far below ground, but in the end the well was marked with a 42 meter (138 feet) tower and fountain, placed a block away from the well itself. The tower was a deft mixture of uses, including a fountain, a sculpture, and an observation deck.

The Évreux Belfry

Pictured above is an illustration from 1825 showing a streetscape in Évreux, France. It was drawn by Richard P. Bonington, and it focuses on the town belfry, which was built from 1490-1497. Bonington does a great job of showing how a tower like this can dominate a streetscape, even if it isn’t that tall by today’s standards.

The Seattle Space Needle and Uninterrupted Verticality

I recently visited the Space Needle while on a trip to Seattle, and the experience was a masterful example of uninterrupted verticality. Throughout the entire visit, I had visual access to my surroundings, and this made the experience much more meaningful than a typical observation tower or skydeck. This is because the lift experience is normally buried deep inside a building, so it doesn’t have views to the outside. This severs the experience of verticality and abstracts the act of ascension and descension. Not the case at the Space Needle, however, and it was fantastic.

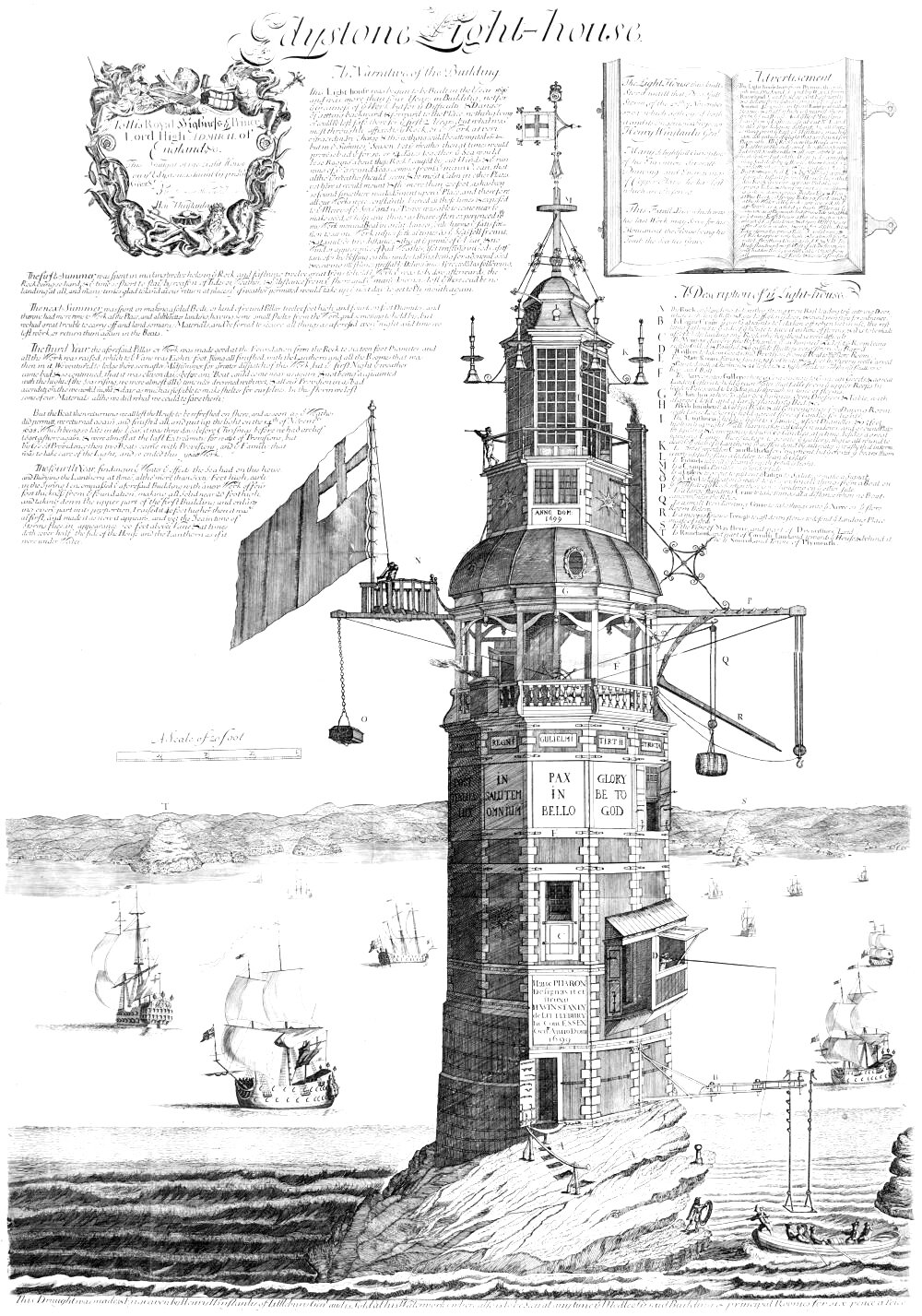

Winstanley's Eddystone Lighthouse

Lighthouse design is all about visibility. These small towers act as beacons for ships at night, alerting captains to various landforms and aiding in navigation. The taller these buildings are, the further away they can be seen. Therefore, the effectiveness of any given lighthouse is based on verticality. Pictured above is the first recorded offshore lighthouse in the world. It was built from 1696 to 1698 off the coast of Southern England, on a shallow reef known as the Eddystone Rocks.

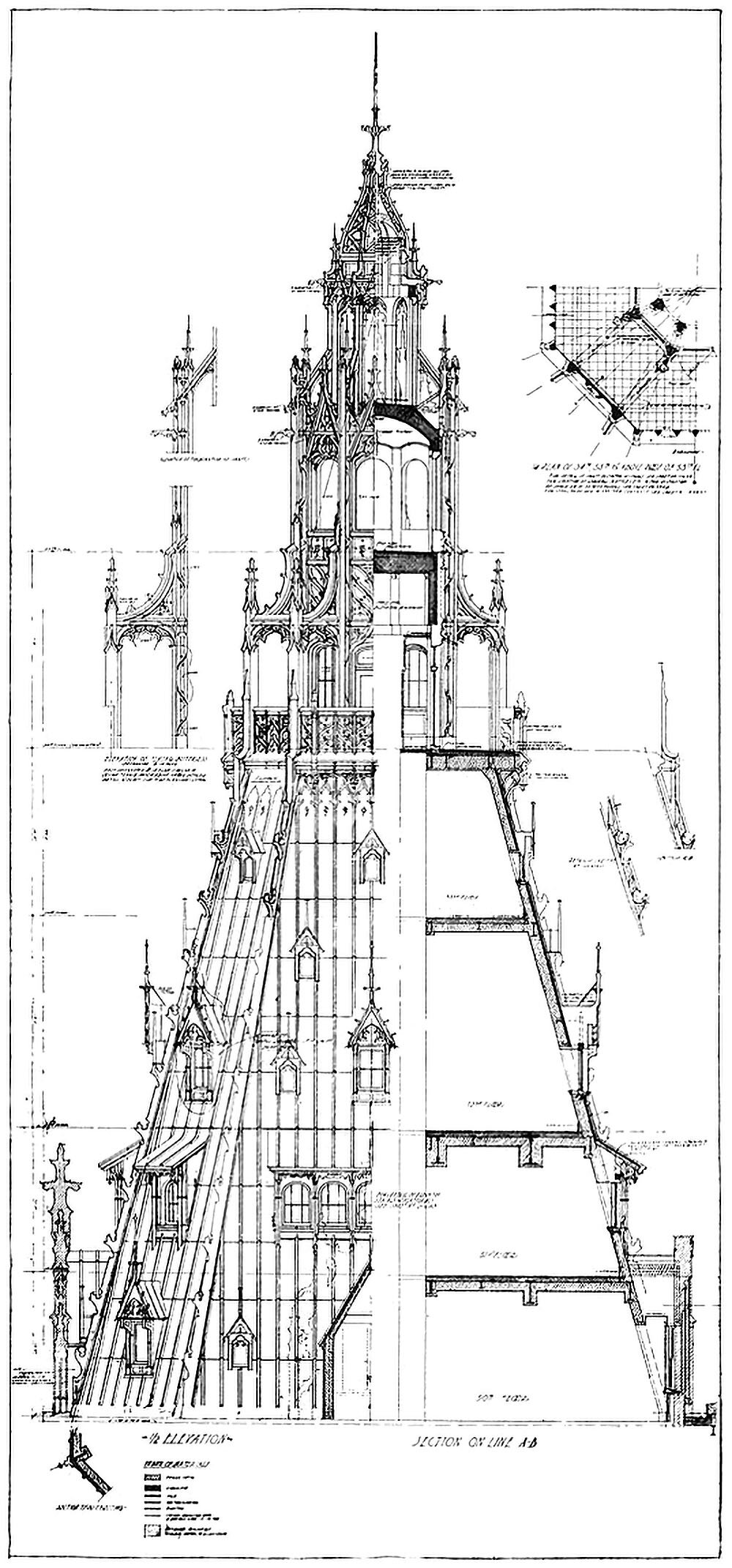

The Woolworth Building and the Question of Ornament

Pictured here is a combined elevation and section showing the crown of the Woolworth Building in New York City. Completed in 1912, the tower was the tallest building in the world at the time, and featured Neo-Gothic detailing throughout. As the drawing shows, this detailing is largely superficial, however. This is highlighted by the stark contrast between the left and right hand side of the drawing. This dichotomy between exterior and interior raises a couple questions related to verticality.

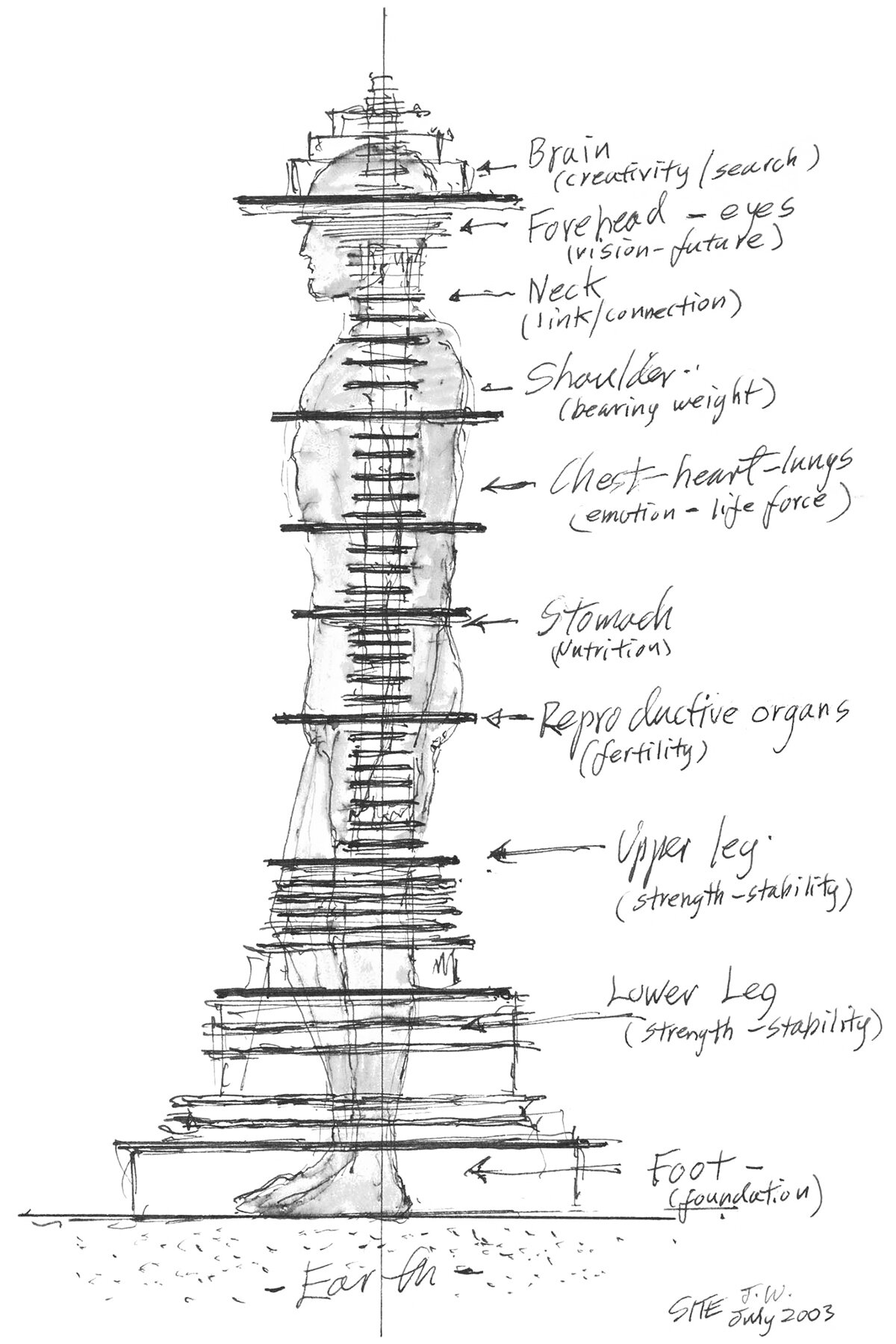

Bipedalism and The Skyscraper

I came across this diagram the other day, and it immediately struck me. It was drawn in 2003 by James Wines of SITE for his Antilia Tower project, and it superimposes a human body on top of a tower section. I’ve previously written about the conceptual link between the bipedal human body and the tower, but this diagram takes it a step further and matches the functions of each part of the body to each part of the tower.

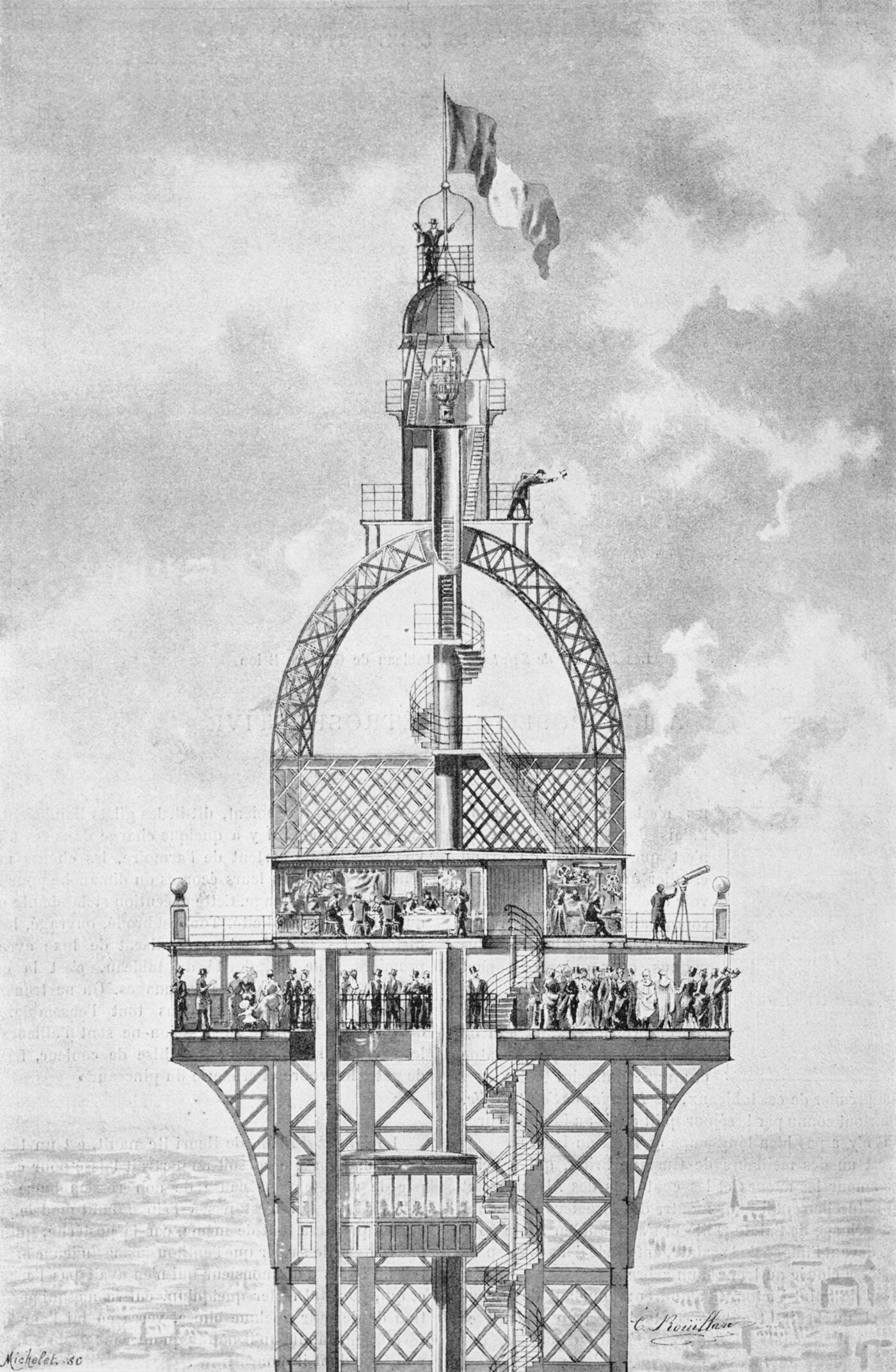

The Secret Apartment at the Top of the Eiffel Tower

Pictured above is an illustration of the Eiffel Tower’s original crown design. You can see the main observation deck, which is packed with people, all enjoying the view atop the tallest building in the world. Unbeknownst to them, however, is the private apartment located on the floor just above them. It was designed by and for Gustave Eiffel as a private space for himself to entertain notable guests and perform scientific experiments. It’s generally referred to as the secret apartment, but it was fairly well-known to the public that Eiffel built the space for himself.

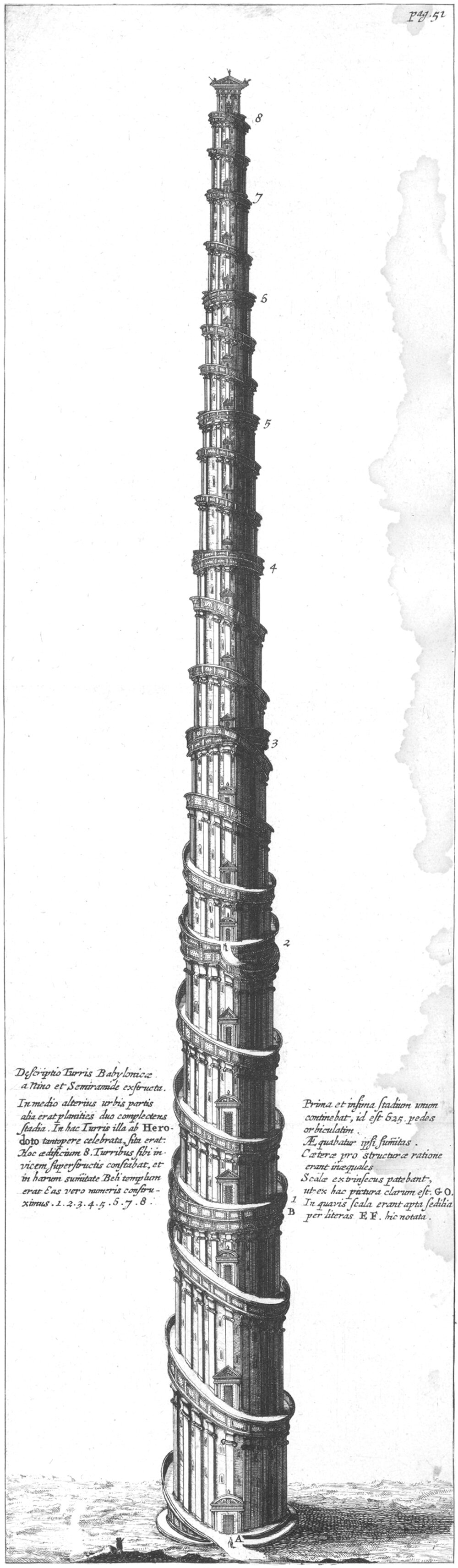

Athanasius Kircher’s Turris Babel

The concept of the Tower of Babel is a timeless one, and throughout history it’s attracted the attention and imagination of myriad individuals. One such individual was Athanasius Kircher, a German scholar and polymath who lived from 1602-1680. His 1679 work Turris Babel explores the concept of building a tower that would reach Heaven, and it was accompanied by a few etchings of such a building.

“Towers have always been erected by humankind - it seems to gratify humanity’s ambition somehow and they are beautiful and picturesque.”

-Frank Lloyd Wright, American architect, 1867-1959

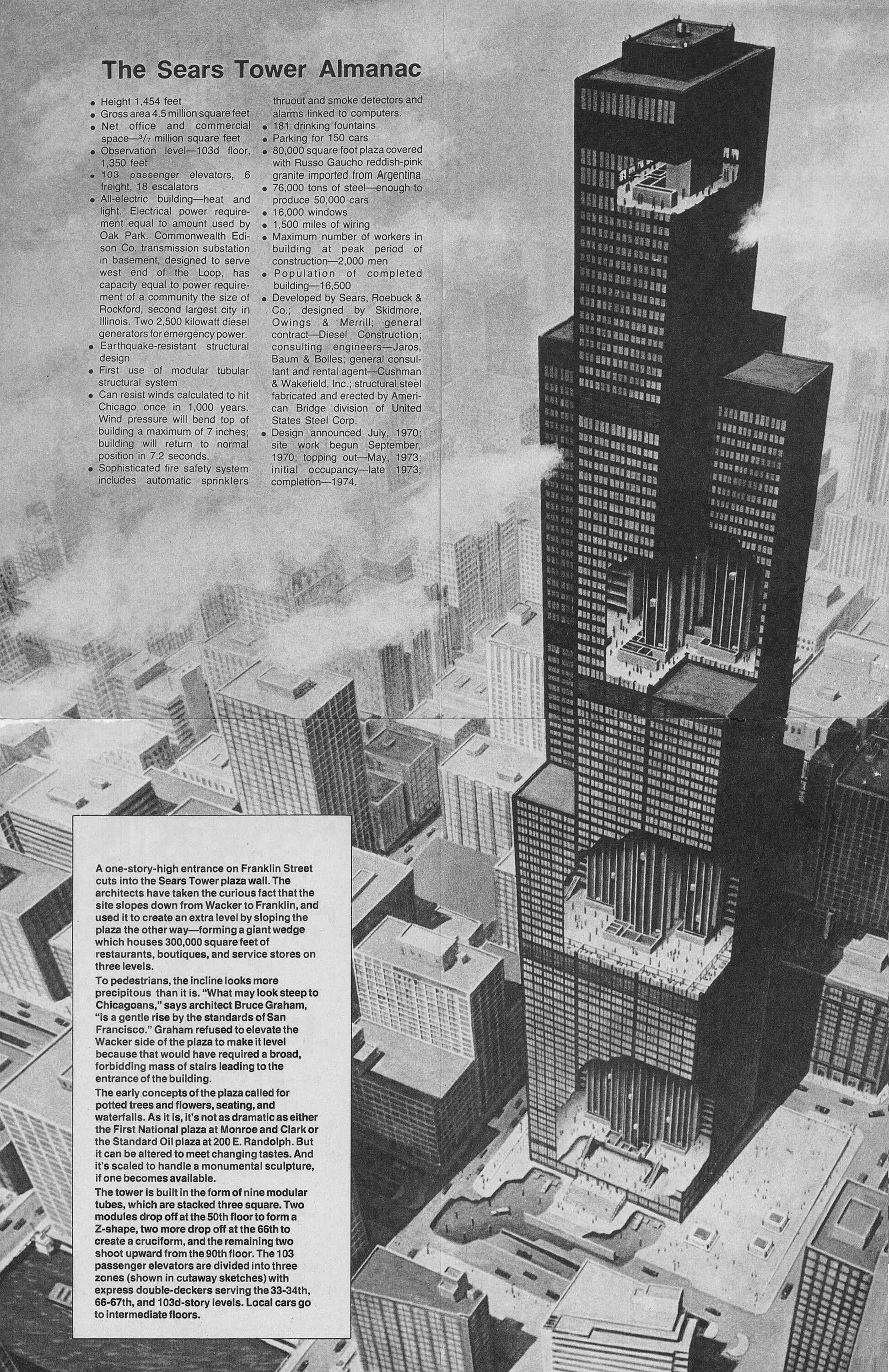

The Original Flat-topped Sears Tower

The above illustration shows the original design for the Sears Tower in Chicago, along with a bunch of factoids related to the scale of the building. Upon first glance, the first thing that stood out to me was the flat roof and lack of the building’s now-iconic antennae. As with most skyscrapers of this size, the building feels quite different without the white spires that are now so closely associated with the skyscraper. Similarly, imagine the Empire State Building without it’s spire, or the John Hancock Center without it’s antennae. It’s just not the same.

The Tower of Babel : A Parable of Verticality

The Tower of Babel is arguably the most storied myth about the human need for Verticality that has survived from antiquity. It’s a legendary tale of a clash between Ego and God, and it acts as a starting point for any worthwhile history of human towers or skyscrapers. Let’s take a look at why it’s been so influential, and why it encapsulates our struggles with Verticality.

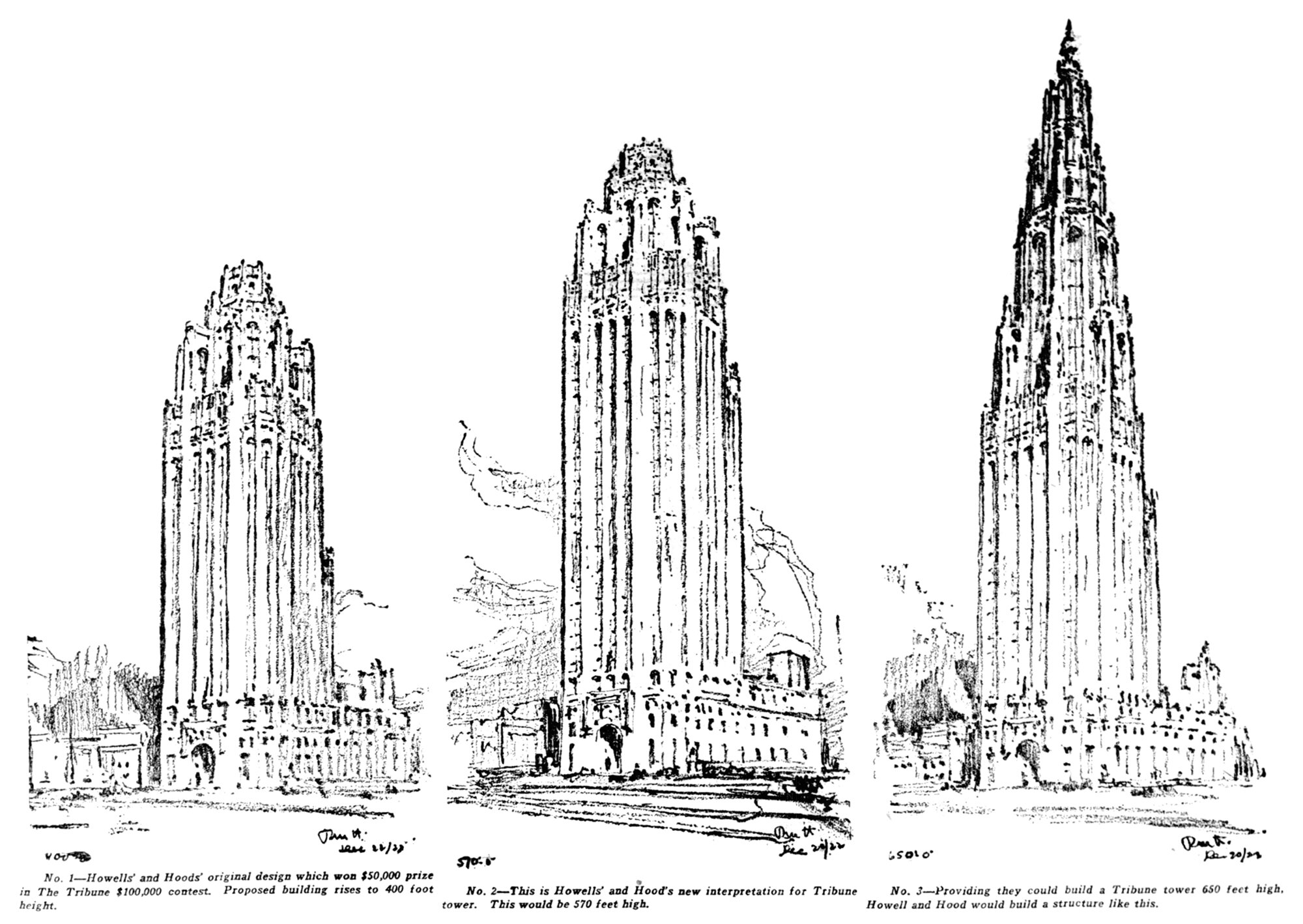

Alternate Realities : Chicago Tribune Tower

Pictured above are three design sketches for the Chicago Tribune Tower. They were drawn after the newspaper asked the architect to study taller options for the building, because they were considering whether or not to build the world’s tallest skyscraper. The increased height would require special approval from the city, so in the end they opted for beauty over height, and didn’t pursue the taller options.

Zoning Envelopes and the New York Skyscraper

Back in architecture school, I had a professor once say that the most effective way to create change is to adjust the building code. That way every architect must conform their designs to meet the code’s requirements, which is much more impactful than any single building could ever be. It was sage advice, and throughout the history of skyscrapers, it rings true. Throughout the history of skyscrapers, arguably the most influential of these changes occurred in 1916 in New York City.

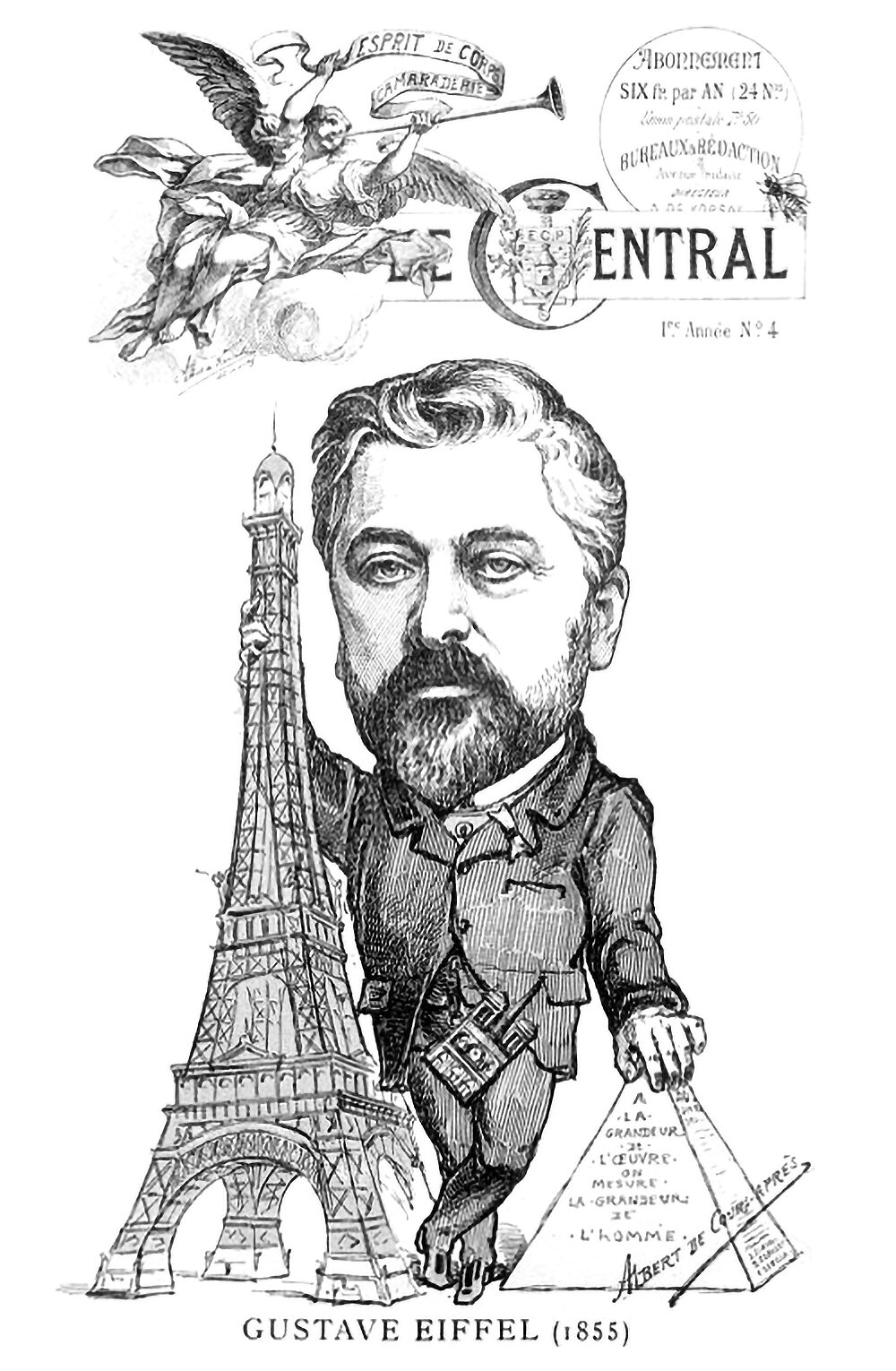

By the size of the work, we measure the size of man

The above illustration is from the cover of an 1889 issue of Le Central. It shows a caricature of Gustave Eiffel standing in between his Eiffel Tower and the Great Pyramid. Inscribed on the pyramid is the phrase A la grandeur de l'oeuvre on mesure la grandeur de l'homme, or By the size of the work we measure the size of man. It’s a statement on verticality, and it illustrates how the height of these structures is their defining characteristic in the eyes of the public.