The Tower of Babel : A Parable of Verticality

1563 painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, titled The Great Tower of Babel. Bruegel shows the tower during construction, with a solid form and a gently spiralling ramp along the outer edge.

The Tower of Babel is arguably the most storied myth about the human need for Verticality that has survived from antiquity. It’s a legendary tale of a clash between Ego and God, and it acts as a starting point for any worthwhile history of human towers or skyscrapers. Let’s take a look at why it’s been so influential, and why it encapsulates our struggles with Verticality.

The tale of the Tower of Babel is from the Book of Genesis in the Old Testament, taking up the first nine verses of Chapter 11. Like many well-known myths, the source material isn’t long, but it speaks volumes. Here’s the tale:

And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said to one another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for mortar. And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth. And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men built. And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do; and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

-Genesis 11:1-9

That’s the entire tale. It’s rather simple, but the concepts it deals with are primal and timeless, which is why it’s stood the test of time and transcended the book it resides in. In a way, there’s an element of this story in every single attempt by humanity to build the tallest structure on the planet.

Lucas van Valckenborch’s 1594 painting Tower of Babel, showing the tower as a ziggurat-like structure, with concentric flat terraces. The tower is shown in the midst of construction, with the upper levels incomplete.

The tale can be summarized quite succinctly. Humans want to satisfy their egos, or make a name for ourselves. We decide to build a tower to reach heaven. We go about building said tower, which angers God. As punishment, God confuses our speech and scatters us across the land. Each of these four statements relates to the Theory of Verticality in some way.

First, we have the primal concept of Ego. Human-beings are self-aware, which means we know we’re all going to die one day. This creates a great amount of anxiety in us, and drives us to do countless things that will allow our memory to continue after our death. We have children, we name various things after ourselves, and we build things that will be on earth long after we die, among many others. The things we build are the main interest here, which leads to the second part of the summary.

One way to satisfy the human ego is to build something that symbolizes power and control over our surroundings. This is the world of architecture, and a tower is the clearest representation of this. The tower represents a conquering of gravity and the ultimate control over our natural environment, as well as the human need to achieve Verticality. It’s no wonder our subjects chose a tower for their exploits when their goal was to reach unto heaven.

Next up is the inevitable conflict between Ego and God. The history of towers and Verticality focuses on this conflict. We originally built tall structures to get closer to God, but the subjects of the story were trying to make a name for themselves by reaching God, effectively asserting that humanity is, or can be, equal to God. God was angered by this, which leads to the conclusion of the story.

The story ends with God confusing our language and scattering us upon the earth. This represents the consequences of humanity letting our collective ego drive our decisions. We’ve since learned what it means to reach the sky through flight and skyscraper design, to be sure, but back then the sky represented the unattainable world of the gods, and we wanted to get there.

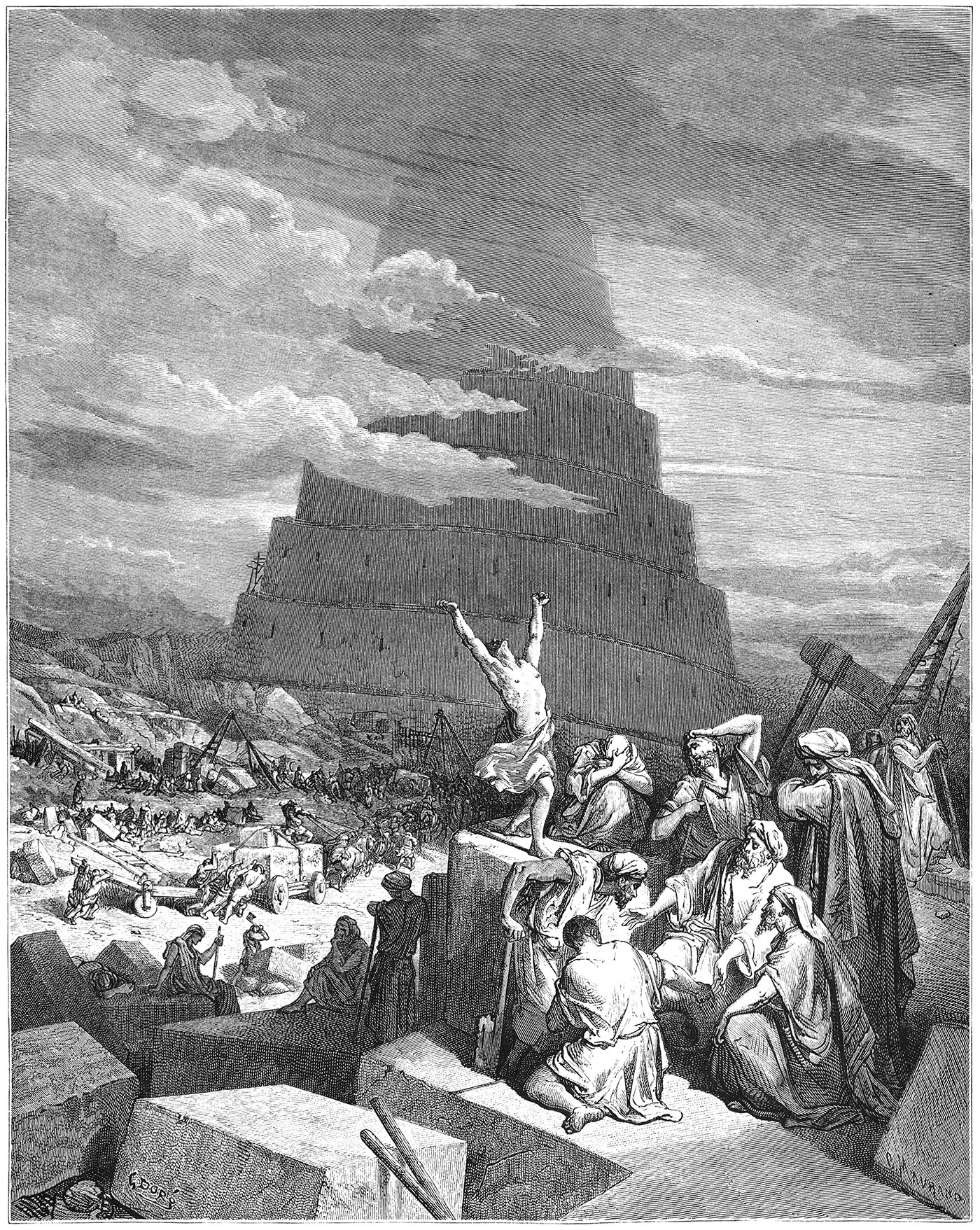

1866 engraving by Gustave Doré, titled The Confusion of Tongues showing the Tower of Babel in the background. This illustration was part of a series of engravings for the Bible, and Doré’s version for the tower is a simple, solid form with a spiraling ramp along the outside, which provides setbacks as the tower rises.

The story of the Tower of Babel contains all the aspects of Verticality. Humans have an innate need to escape the surface of the earth, and throughout our history we’ve put an untold amount of time and energy trying to do this. Our most conspicuous attempts have been tall buildings, which the Tower of Babel crystallizes into a short parable. The tale strips out the details and nuance, and only states that we wanted to make a name for ourselves. We wanted to achieve Verticality, and we believed a tower was the best way to do it. It doesn’t describe much beyond this, so it’s up to us to imagine what it looked like, how it was built and how it would function after it got built.

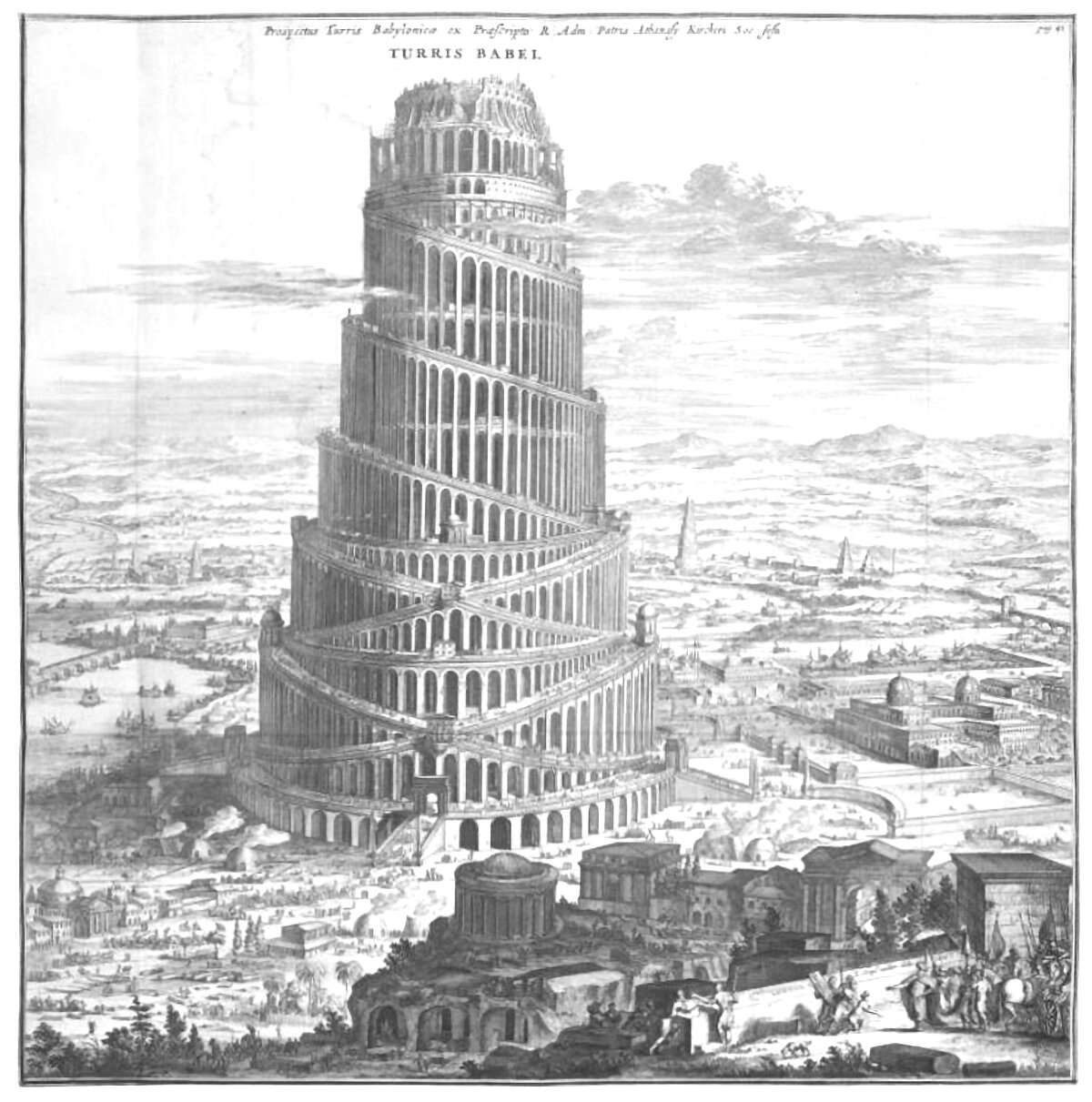

The Tower of Babel has been depicted numerous ways throughout history, and I’ve included a few of the more famous examples here. They range from simple, spiraling forms to more elaborate systems of arches and buttresses. Had the tower actually been real, it most likely would’ve appeared similar to the illustration above by Gustave Dore. The simple spiraling setback is more in line with construction techniques from that time period, as well as the lack of detailed ornament that some other renditions feature. Still, it’s fascinating to see different interpretations of the tower from different time periods, and it goes to show just how influential the story has been.

A 1679 illustration of the Tower of Babel, from Athanasius Kircher’s book Turris Babel. The tower is shown with Roman arches throughout, and a double-spiral ramp that runs between flat terraces.

Taken at face value, the story of the Tower of Babel is a simple tale, but it speaks volumes about humanity and our need for Verticality. At it’s core, the story is about humanity letting our collective ego get away from us, and suffering the consequences as a result. Also, it’s telling that the author chose a tower for such a tale. Even back then, humans had an innate need to escape the surface of the earth, and a tower was seen as the best way to achieve it. In the end, what we’re left with is a simple parable that has given rise to myriad interpretations throughout history, and it’s still as relevant today as it ever was. We may not be trying to reach God with our towers anymore, but we’re still trying to escape the earth’s surface, and we’re still putting enormous amounts of time and effort in doing so.

Read more about how the Tower of Babel ties into the Theory of Verticality.