Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

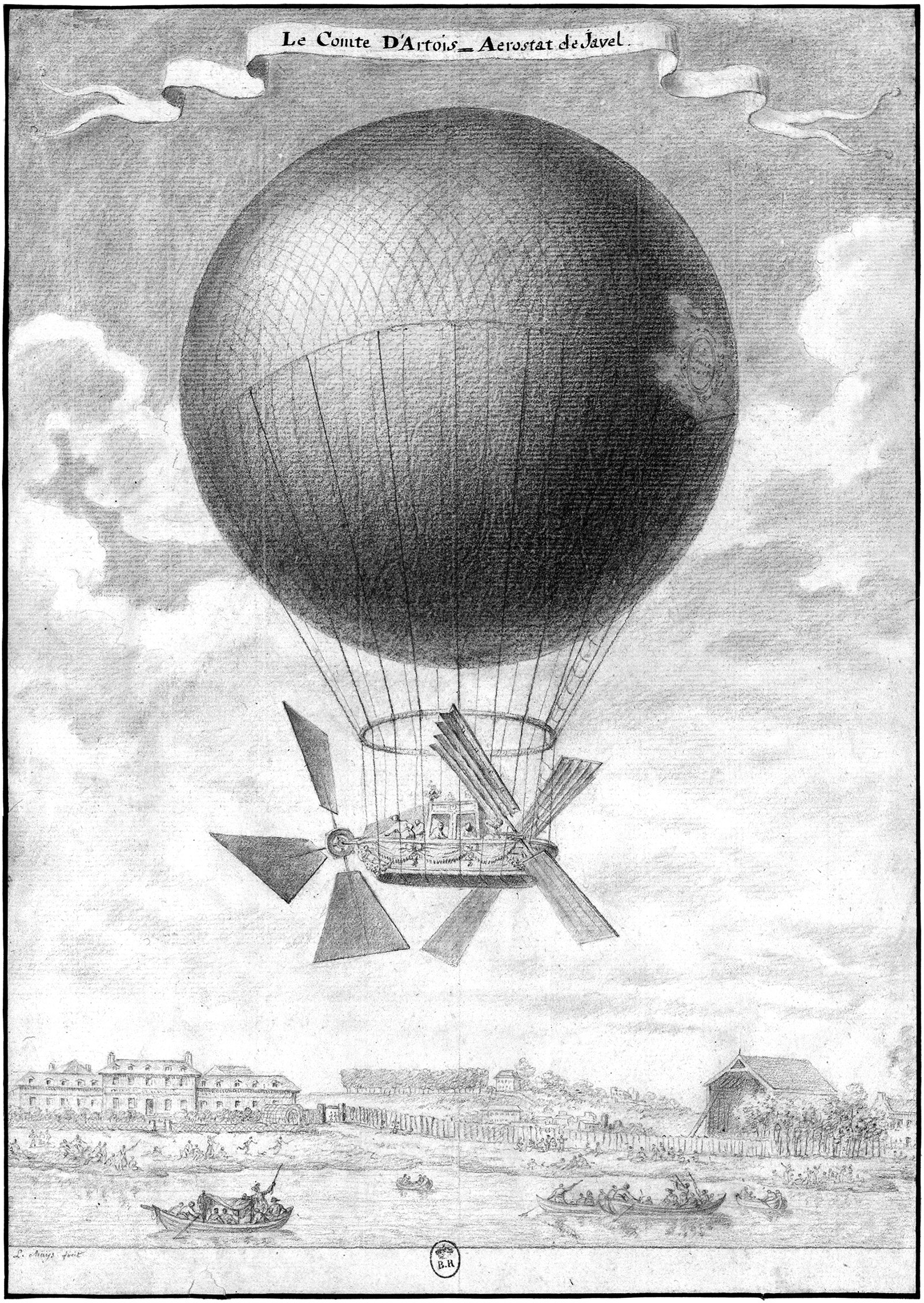

Alban & Vallet’s Comte d’Artois

Pictured above is a design for a flying machine by Léonard Alban and Mathieu Vallet from 1785. It was called Comte d-Artois, or l'Aérostat de Javel. It had a helium-filled balloon which carried a gondola. At one end of the gondola was a large propeller and at the other end was a pair of paddles. The gondola could comfortably seat four people and resembled a shallow boat. Throughout 1785, Alban and Vallet made many successful flights around Paris with the craft, and they also made three notable advancements in ballooning technology along the way.

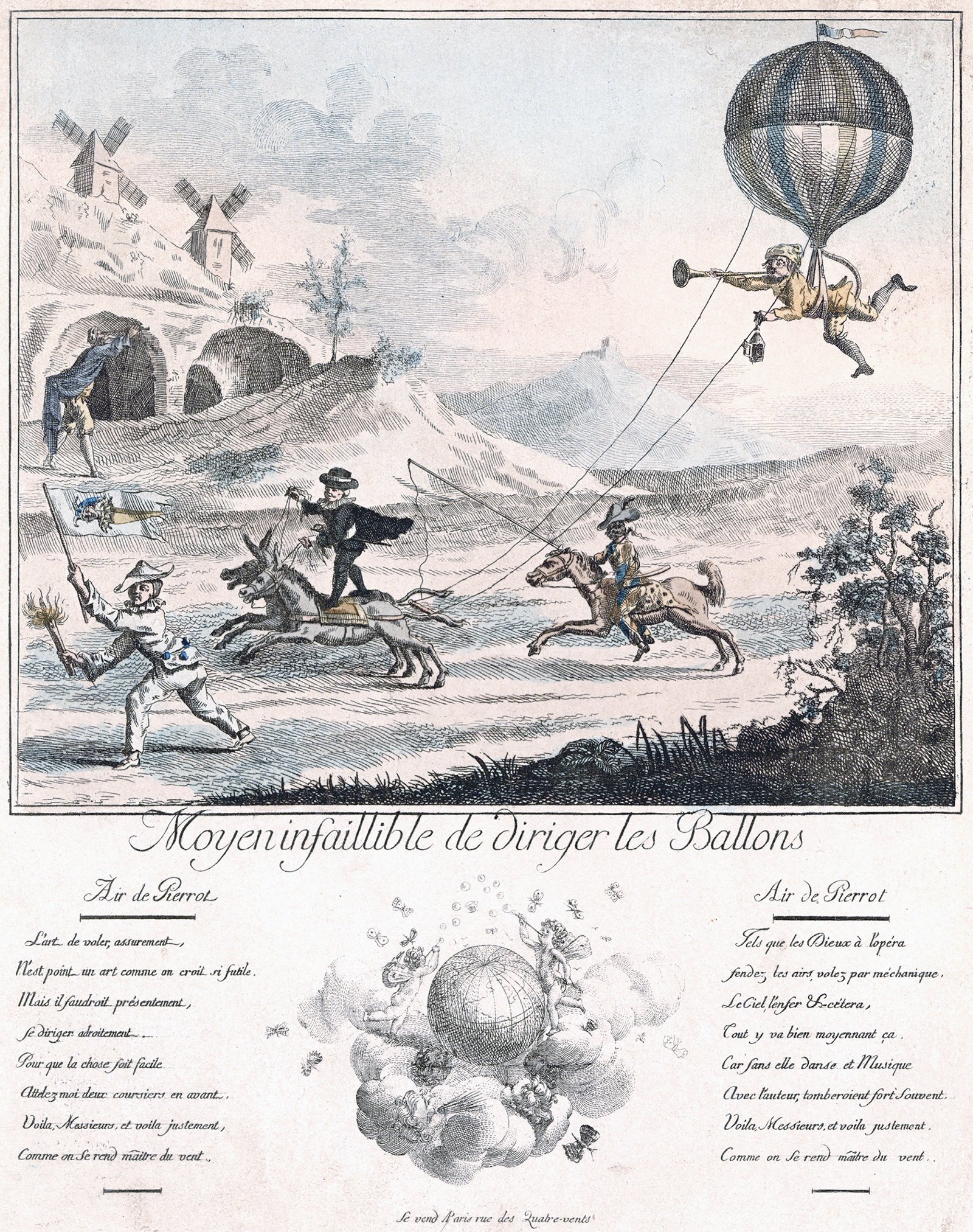

A Foolproof Way to Direct the Balloons

The above illustration shows a comical scene involving a man suspended from a balloon being pulled by a pair of horses. It was drawn in 1787 and it’s titled Moyen Infaillible de Diriger les Ballons, or A Foolproof Way to Direct the Balloons. It’s meant to be a satirical take on ballooning at the time, when flight was front-and-center on the public stage. The characters in the scene are from commedia dell'arte, which is a type of theatre with recurring archetypal characters.

Richard Pearse and a Claim to the World’s First Powered Flight

Pictured above is a photograph of a monoplane designed and built by Richard Pearse in 1903. Pearse was a farmer who had an interest in engineering, flight and flying machines. He had previously designed bicycles and engines, but in the early 1900s he was working on a design for a flying machine. It was a monoplane with a front-mounted propeller and a large wing constructed of a bamboo frame and canvas.

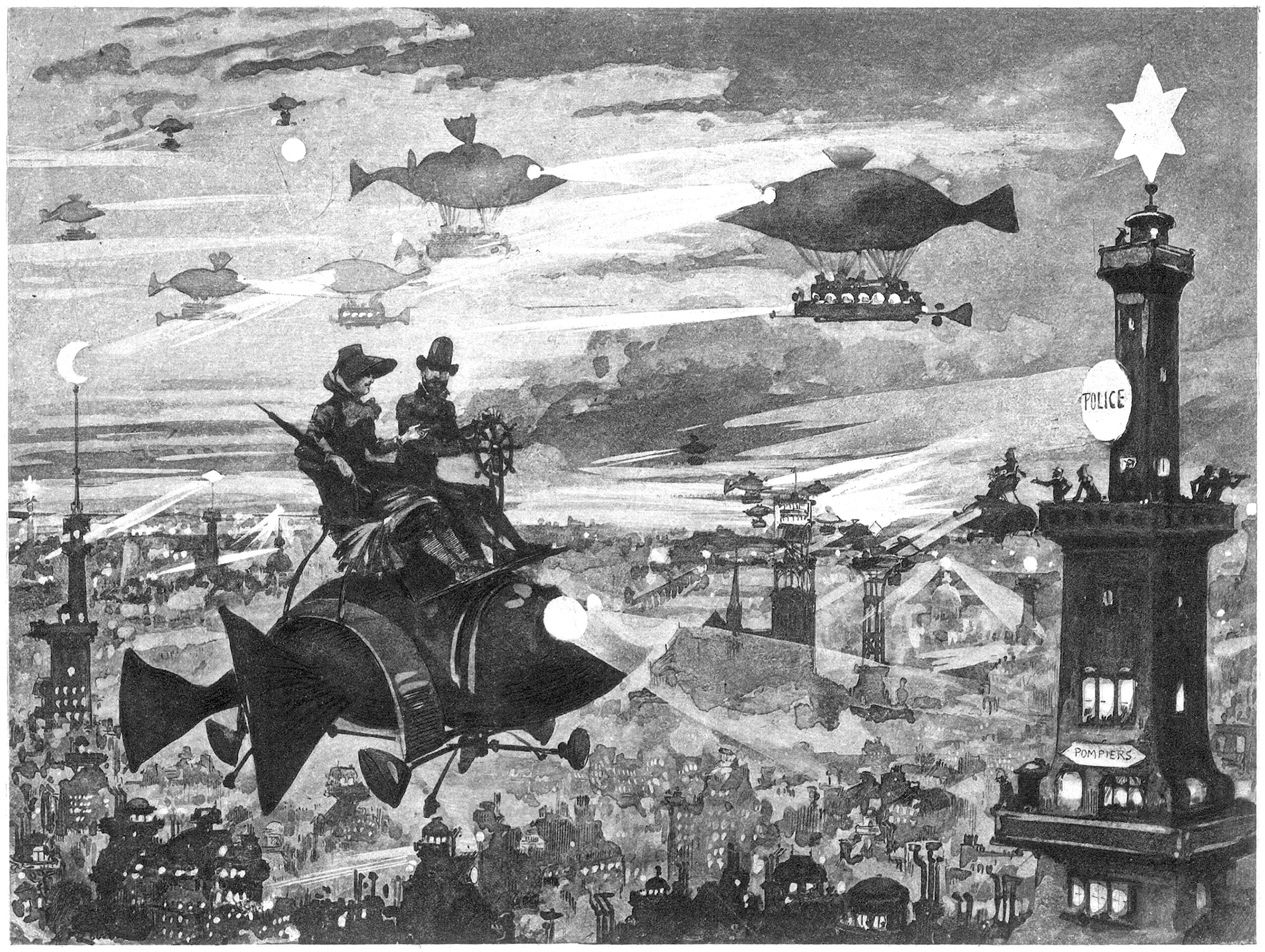

Albert Robida’s Vision for Paris

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. The novel describes a future vision for Paris in the 1950’s, focusing on technological advancements and how they would affect the daily lives of Parisians. Here he shows a vision for the night sky above Paris, which is dotted with various types of flying machines.

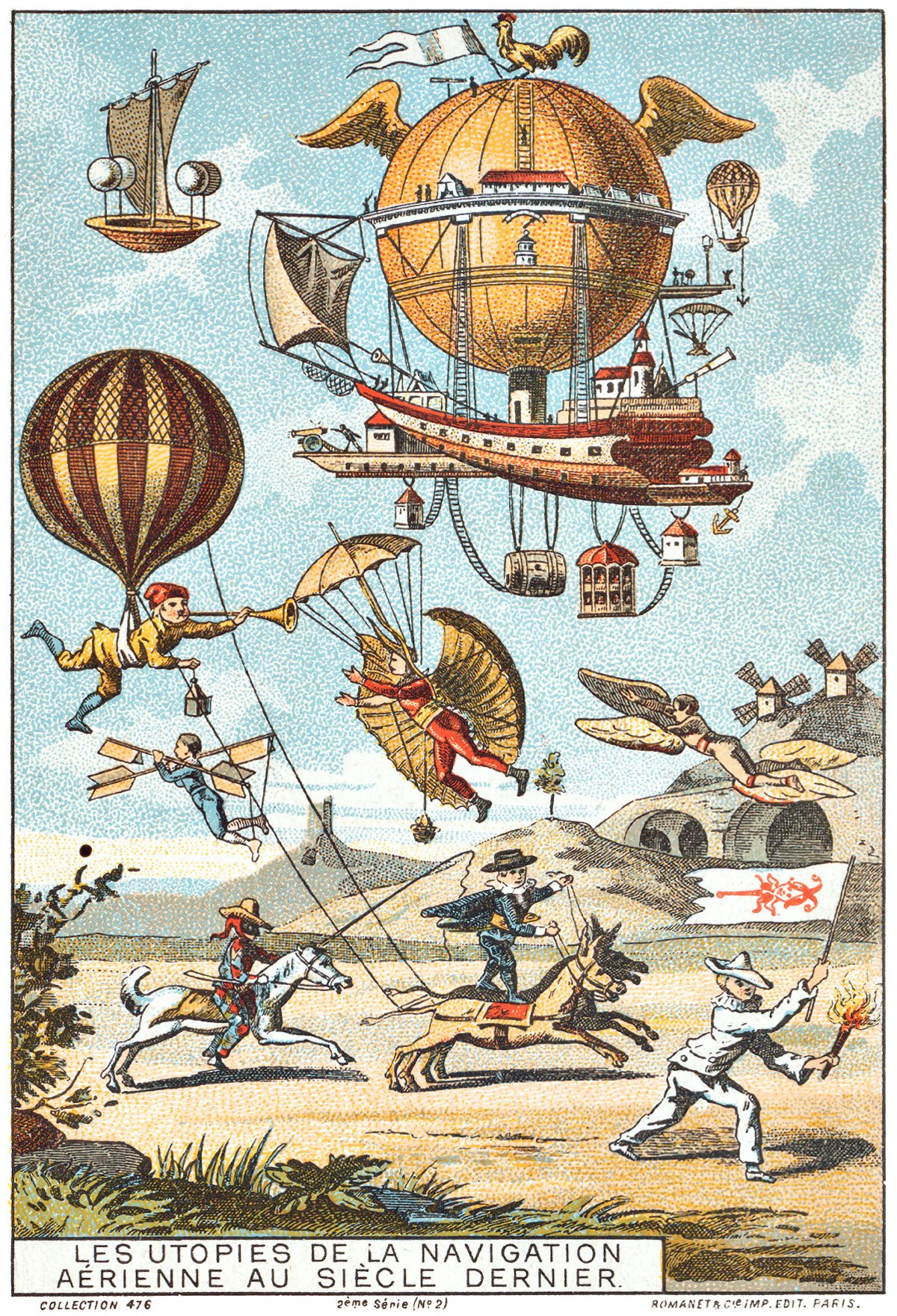

Utopian Flying Machines of the Previous Centuries

Pictured above is a French illustration from 1890, showing a collage of French flying machine ideas from the previous few centuries. The caption reads Les Utopies de la Navigation Aérienne au Siècle Dernier, which means The Utopia of Air Navigation in the Last Century. There are six flying machine ideas shown together in the sky.

The Wright Flyer and the World’s First Powered Flight

Upon a flat plain outside the town of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903, a home-made flying machine lifted off the ground into a headwind. It landed twelve seconds later and 37 meters (120 feet) away from its launch point. This short distance marked the first time in the history of humankind that a manned, heavier-than-air craft had flown under its own power. This event would cement its creators into the pantheon of technological pioneers and make them a household name.

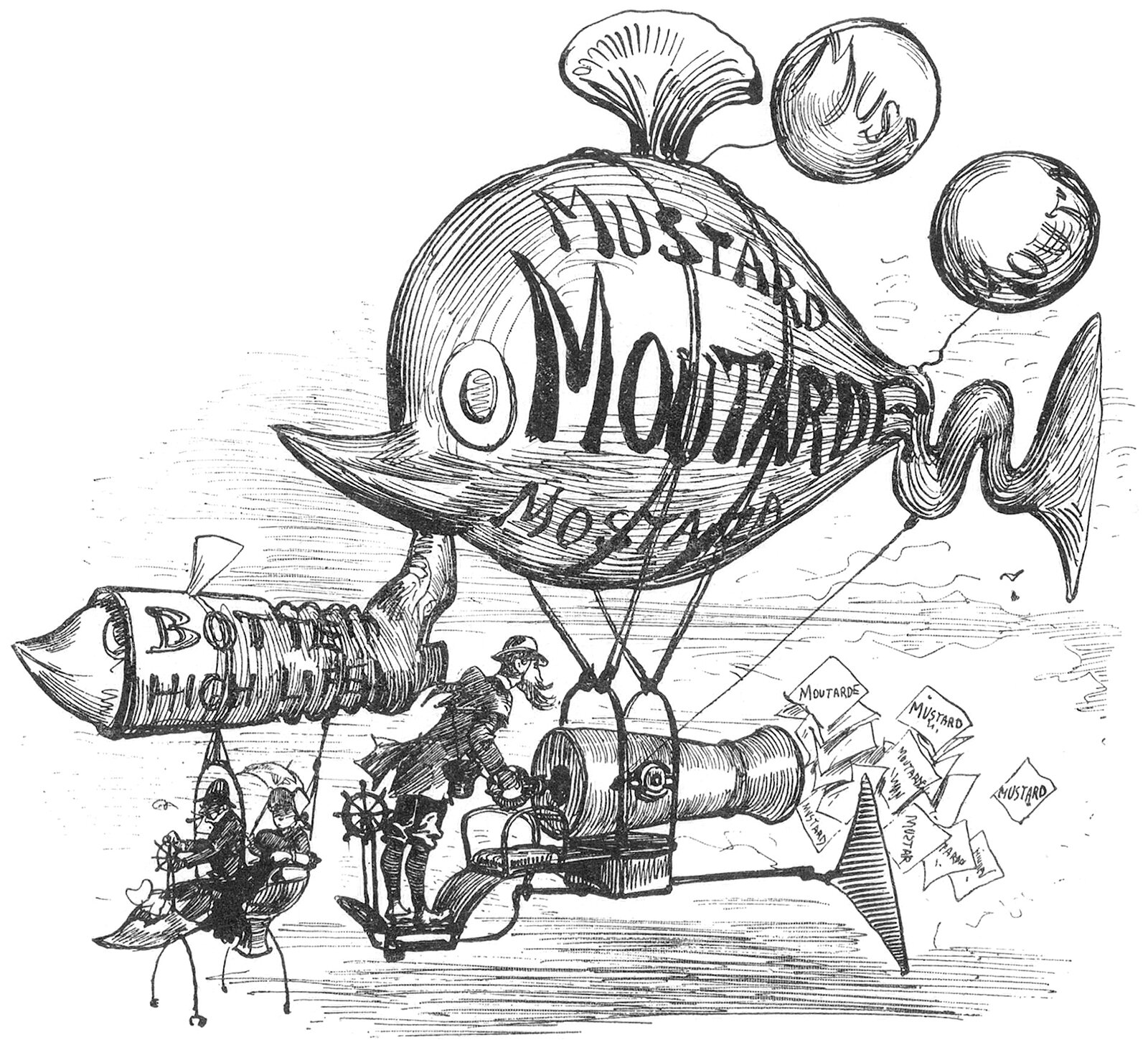

Albert Robida’s Flying Advertising Machines

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. The novel describes a future vision for Paris in the 1950’s, focusing on technological advancements and how they affected the daily lives of Parisians. Here, he shows a pair of flying machines meant for advertising.

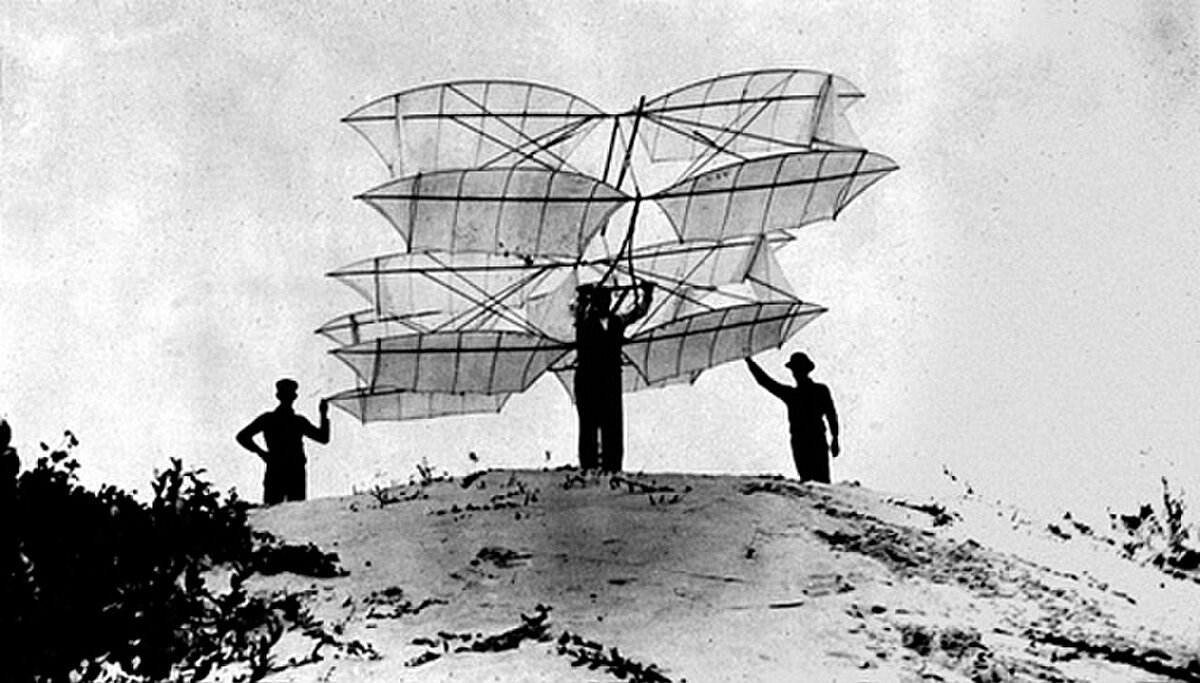

Octave Chanute’s Glider Designs

Pictured above is a twelve-winged glider designed by Octave Chanute in 1896. It’s one of many flying machines Chanute experimented with, and like these others, it directly influenced other pioneers of aviation. Chanute began his career as a civil engineer, and he made a name for himself building railroads and bridges. After retiring in 1883, he turned his attention to aviation, which was a subject he’d been interested in for decades prior.

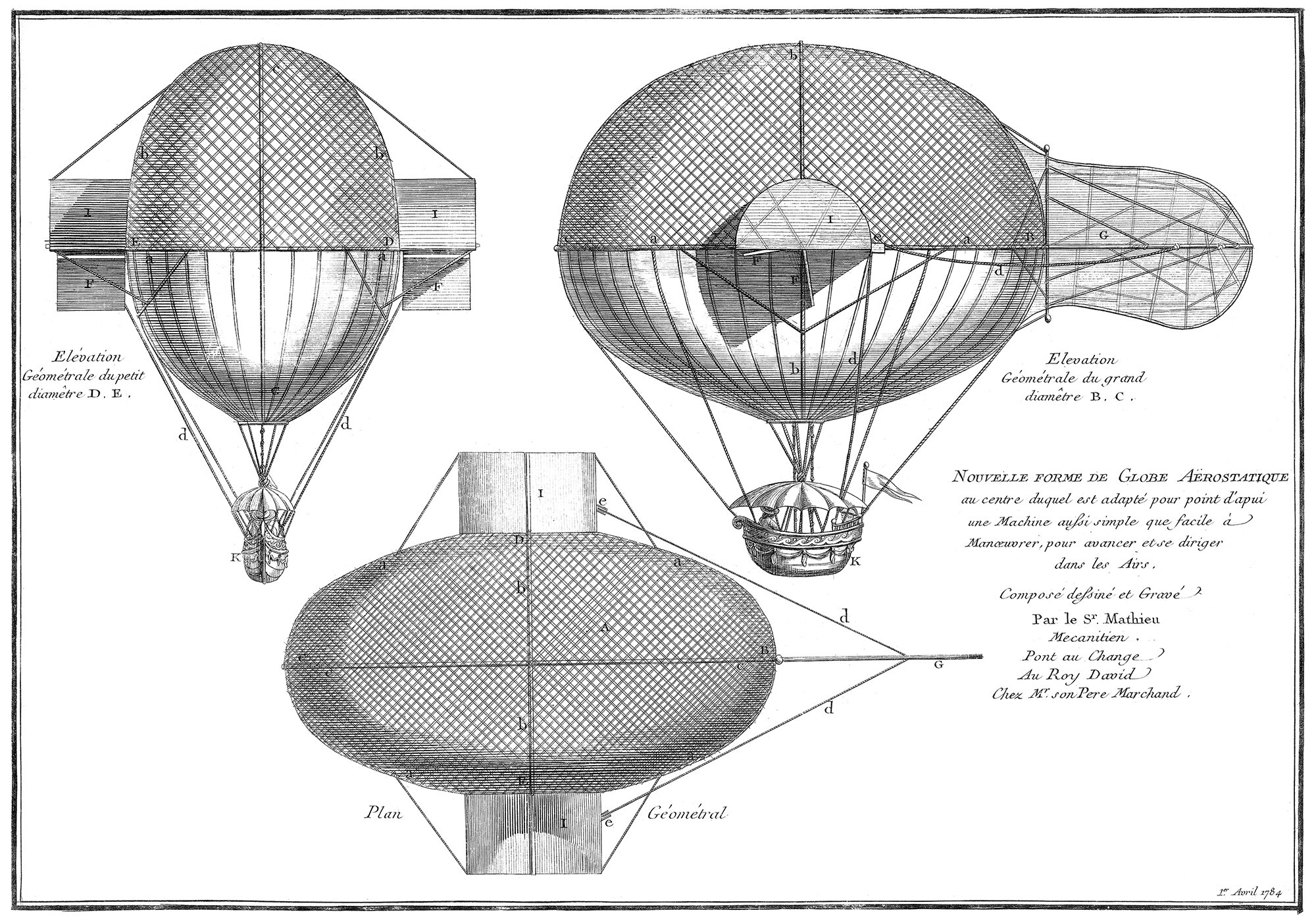

Jean Mathieu’s Aerostatic Balloon

This is a 1784 design for a finned balloon, designed by Jean Mathieu. It’s called Nouvelle Forme de Globe Aërostatique, which means New Shape for an Aerostatic Balloon. It’s an interesting one, because it’s unclear how it’s supposed to propel itself through the air. The design consists of an ellipsoidal balloon with a small basket underneath, housing two pilots, as well as two side hoods and one rear fin.

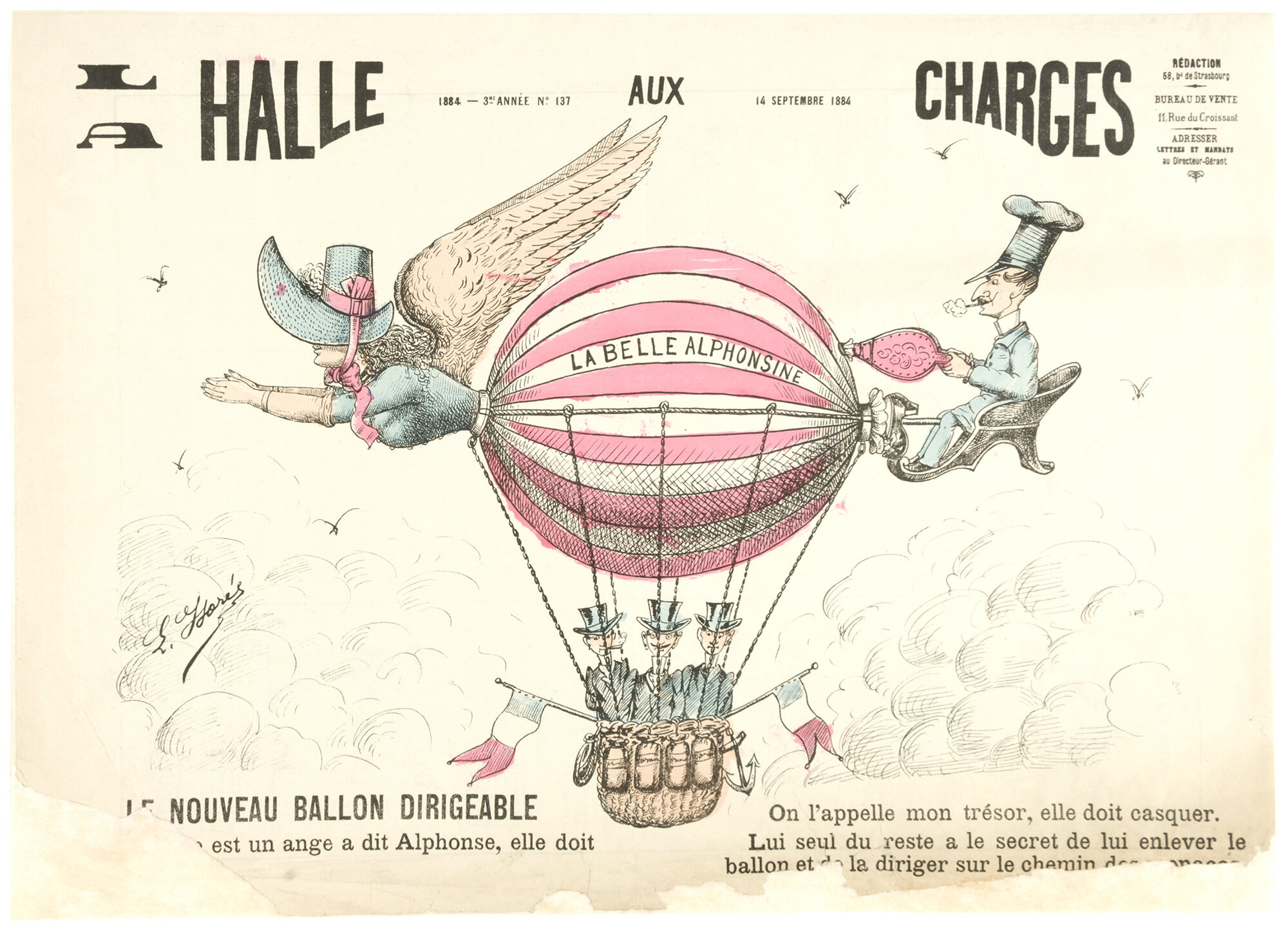

La Belle Alphonsine by E. Florés

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the human quest for flight was continuously on the public’s mind, and the above illustration is a testament to this. It’s from the front page of a French newspaper called La Halle aux Charges from 14 September 1884. This newspaper was well-known for it’s political caricatures and social commentary, and their choice to put a fictional balloon on their front cover is the perfect representation of what a successful flight means for all those involved.

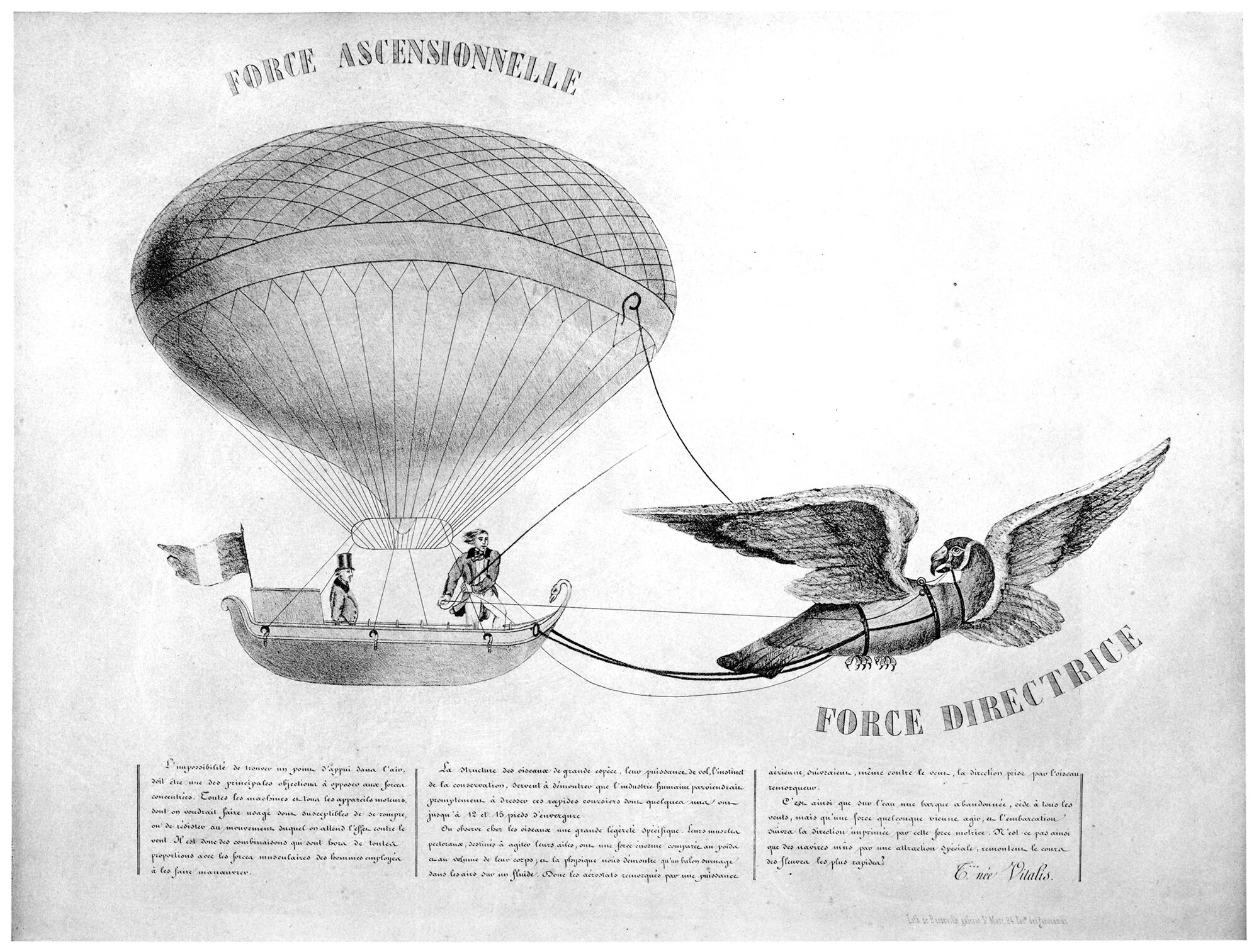

Tessiore’s Balloon Project Towed by a Tame Vulture

Pictured above is a design for a flying machine, consisting of a balloon pulled by a tame vulture. It was originally published in 1845, and was re-published in 1922 in the book L’Aeronautique des origines a 1922. The title of the illustration is Projet de Ballon Remorqué par un Gypaète Spprivoisé, or Project for a Balloon Towed by a Tame Vulture. I’m unable to find any data on the image apart from this, but the content itself is enough to discuss, for obvious reasons.

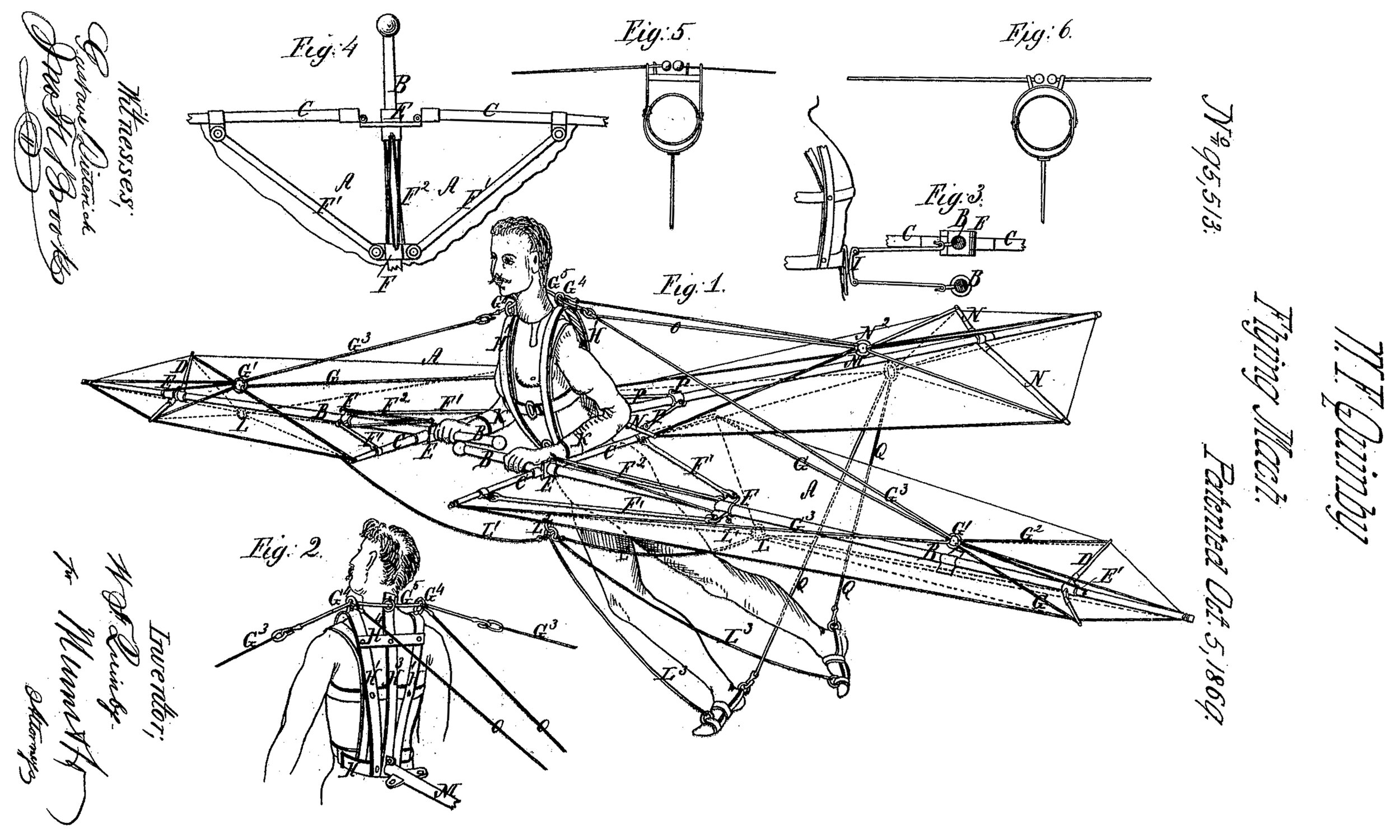

W.F. Quinby and his Three Flying Machine Patents

Pictured above is a patent drawing for a flying machine, designed in 1869 by Watson Fell Quinby, or W.F. for short. It’s the second of three patents for flying machines that Quinby has to his name. It shows a man flying with three wing-like sails attached to him, along with some rudimentary controls at his hands and feet. As with all of Quinby’s designs, we don’t have any photos to compare the patent drawings to, so we’ll have to assume that if he built any prototypes, they weren’t successful.

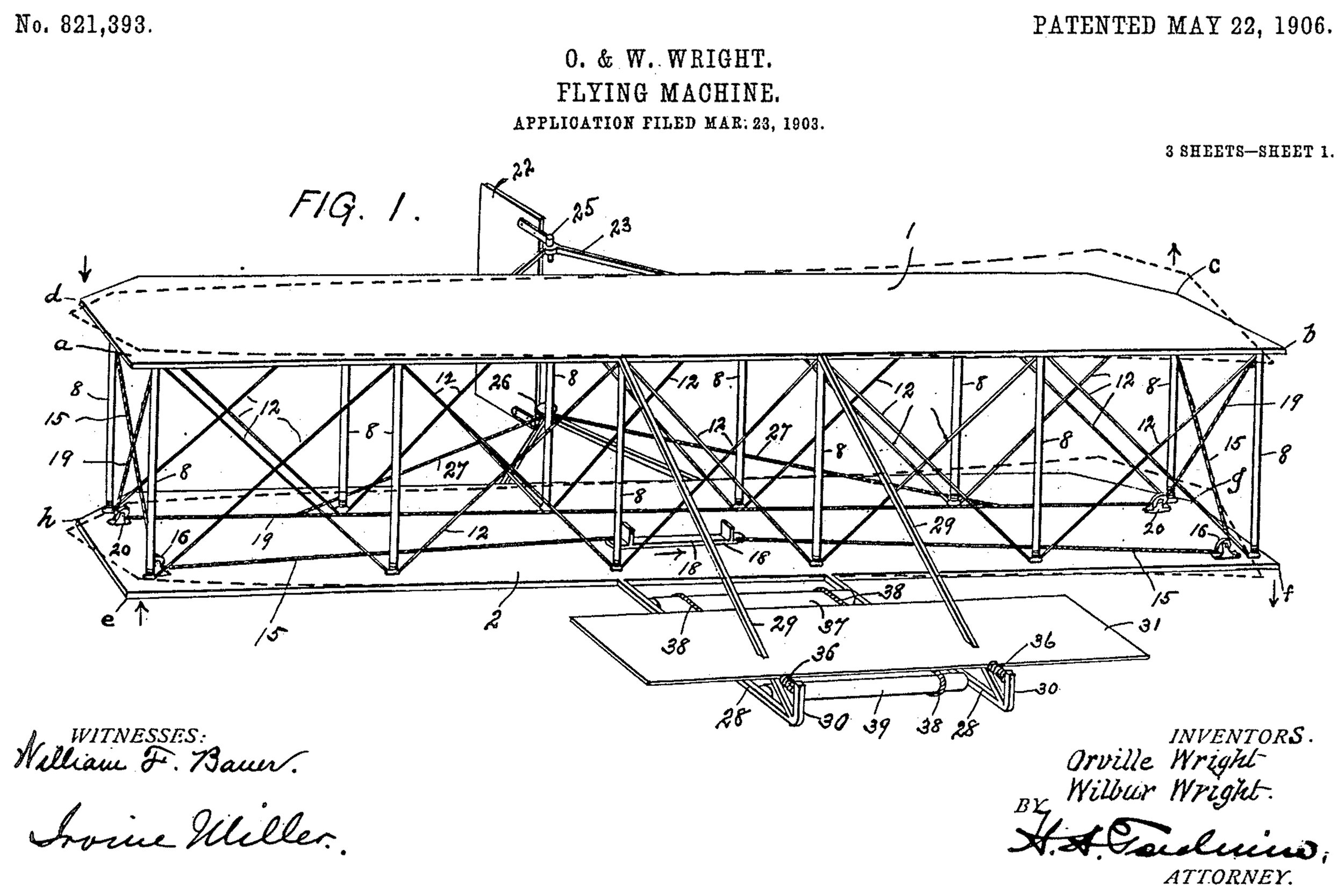

The Wright Brothers’ Flying Machine Patent

I find it fascinating to look at patent drawings of iconic designs throughout history. It’s like you’re getting a glimpse of the design process, before an object enters the public consciousness. Pictured above is a patent for the Wright Brothers’ flying machine, which has since become synonymous with the first ever powered flight. I love how drawings like this strip away any artistic style or vision, and just focus on the object itself. This is a hugely important object that lives on in the history of aviation and human achievement, but it’s rendered here in the most basic, unpretentious way.

Flying Carpets and the Power of Flight

Flying carpets are the things of folk tales and fantasy. They are magical objects with the power of flight, and anyone who owns one has considerable power over those who don’t. They can quickly transport their owners across the land at great speeds, and they allow their owners to achieve verticality. Here’s a look at the folk tales that established the myth of the flying carpet.

The Isolation of Flight

Have a look at the above illustration. It shows an airship high up in the clouds, isolated and alone up in the sky. This view encapsulates the idea that humans are surface-dwellers, and we’re not built for a life in the clouds. Throughout our history, we’ve spent untold amounts of time and energy trying to escape the surface of the earth, but the reality of such an escape is so foreign to our needs, that it creates a conflict within us.

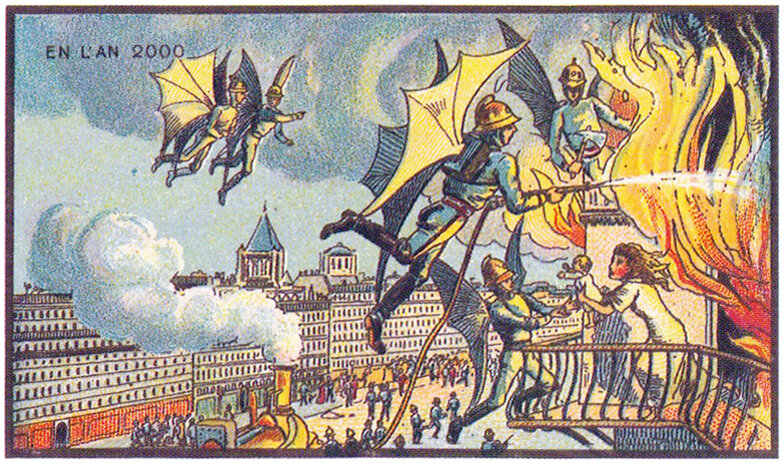

En L’An 2000 : In The Year 2000

Imagine a future where flight is commonplace, and the skies are full of flying people, including police officers, fire fighters, postman, and countless others, zipping around above our heads. That’s what a group of artists led by Jean-Marc Côté dreamed up in 1899 when asked to imagine light-hearted inventions that would contribute to the future. The result was a series of nearly 90 vignettes called En L’An 2000, which means In the Year 2000. The pieces were originally printed as cigarette cards, and later made into postcards. They include a variety of subjects, with a distinct focus on flight and flying machines.

Tito Livio Burattini’s Flying Dragon

The above sketch is by Italian engineer Tito Livio Burattini, drawn sometime between 1647 and 1648. At first glance, it’s hard to reconcile a sketch of a flying dragon with a serious proposal for human flight, but Burattini had spent quite a bit of time researching flight, and the sketch was part of a larger treatise on the subject. It was titled Ars Volanti, and throughout the text Burattini wrestled with the idea of flight and how it may be achieved.

Pierre Ferrand’s Corkscrew Airship

This is Pierre Ferrand de Montfermeil’s 1835 design for an airship, featuring a giant screw mechanism and an elaborate system of fins. Unfortunately details of the design are scarce, and this appears to be the only image we have. According to the authors of the book L’Aéronautique des origines à 1922, it originallt appeared in a brochure titled Projet pour le Direction de l'Aérostat par les Oppositions Utilisées, or Project for the Direction of Airships used by Oppositions.

The Unpretentious Philosopher

Check out the above illustration. It’s the frontispiece to Louis Guillaume de La Follie’s science-fiction work La philosophe sans Pretention, or The Unpretentious Philosopher, from 1775. What’s most interesting about it is the flying machine featured in the drawing, evidenced by the crowd of onlookers in awe of it.

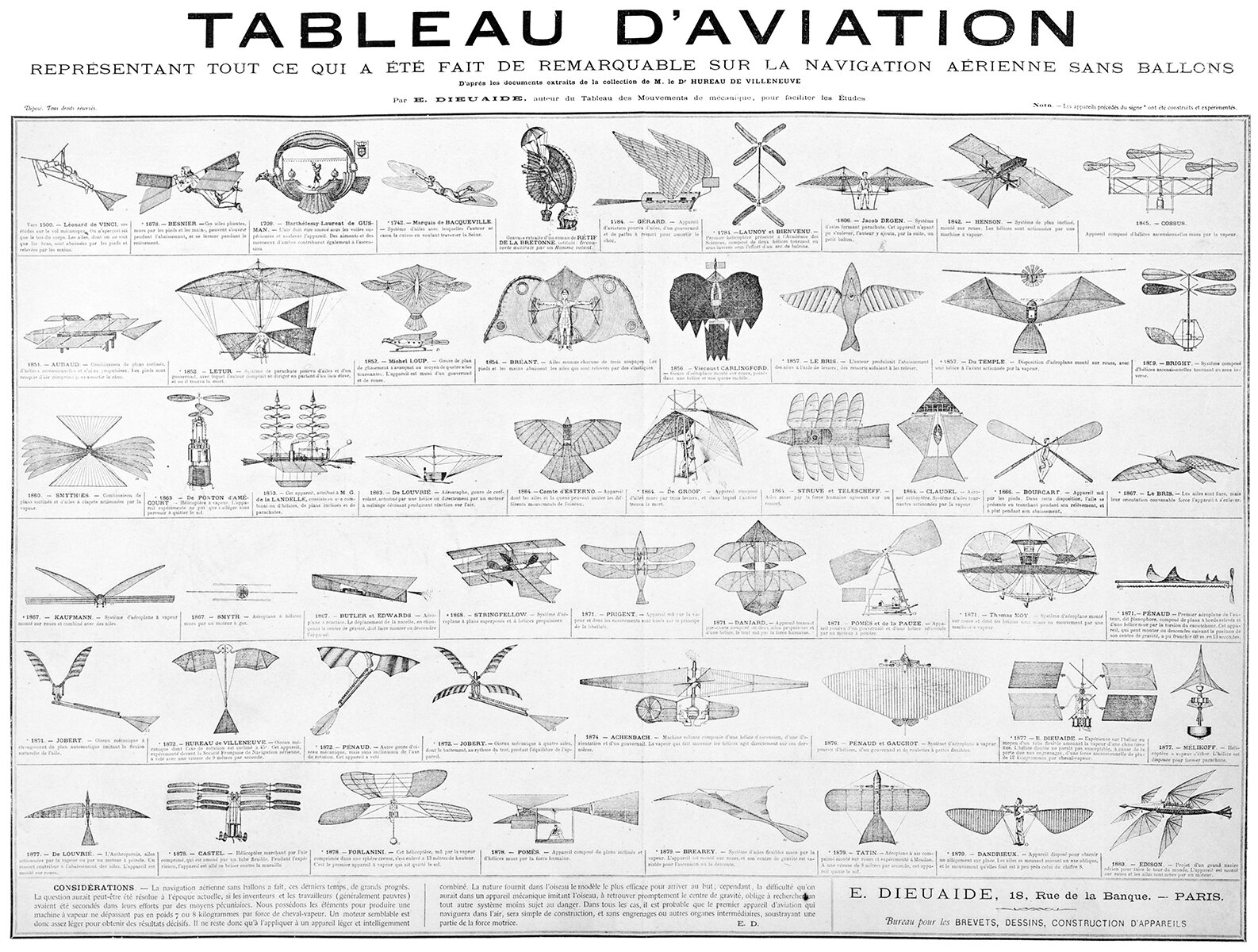

Tableau d’Aviation

The creativity and ingenuity on display throughout the history of flying machines is amazing. A quick survey of the table above shows the wide variety of ideas tried out before we humans successfully learned how to fly. One thing I love about this table is that it includes fictional flying machines as well as real prototypes. This shows that fictional designs can and have influenced the history of flight just as real prototypes have.