The Wright Flyer and the World’s First Powered Flight

Photo showing the first successful flight of the Wright Flyer on December 17, 1903 outside Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Orville Wright is piloting the craft while Wilbur Wright runs alongside it. This marked the world’s first sustained flight by a manned, heavier-than-air craft under its own power.

Upon a flat plain outside the town of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on 17 December 1903, a home-made flying machine lifted off the ground into a headwind. It landed twelve seconds later and 37 meters (120 feet) away from its launch point. This short distance marked the first time in the history of humankind that a manned, heavier-than-air craft had flown under its own power. This event would cement its creators into the pantheon of technological pioneers and make them a household name. The photo above shows the flight. The man piloting the aircraft was Orville Wright, and the man running alongside it was Orville’s brother, Wilbur. They had been taking turns piloting the craft, and on this day it happened to be Orville’s turn. It was a breezy day, and a strong headwind provided the lift necessary for the craft to fly. The rest is, as they say, history.

Wilbur and Orville Wright were born in 1867 and 1871, respectively. In 1889 the brothers began their professional careers in the printing business after designing and building their own printing press. This lasted until 1892, when they opened a bicycle repair and sales shop. In 1896 they began manufacturing their own brand of bicycles, which they would use to fund their nascent interest in flight. They were subsequently exposed to the work of Octave Chanute, Otto Lilienthal and Sir George Cayley in the mid-1890s, and developed an obsession with human flight after learning of Lilienthal’s death while experimenting with one of his gliders. In 1899, they began designing and testing kite designs before moving to Kitty Hawk the following year to begin their experiments into manned flight.

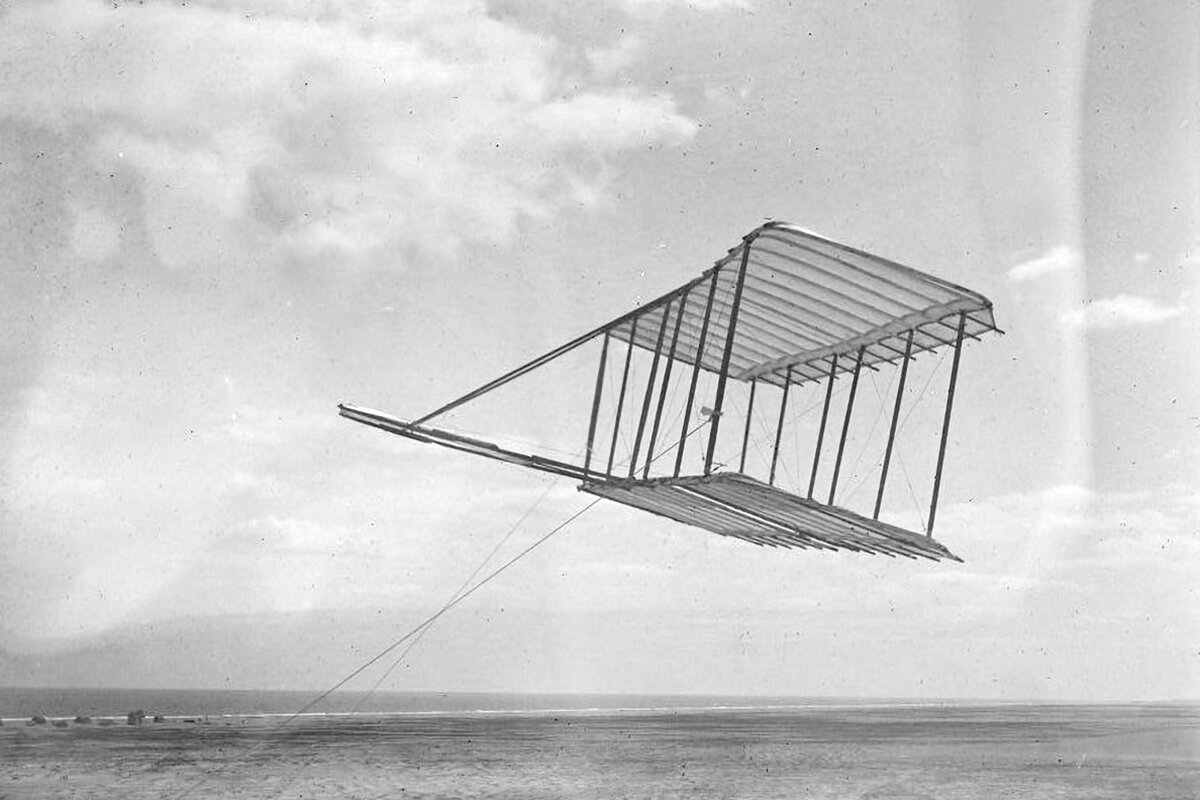

The Wright Brothers’ first glider design from 1900. This craft was capable of sustained flight when flown like a kite.

Once they arrived at Kitty Hawk, the Wright Brothers would subsequently develop and test a series of glider designs. Their first design, from 1900, is simply called the 1900 glider. The design was directly influenced by Octave Chanute’s bi-wing glider designs from 1896-97, and the Wrights would collaborate with Chanute throughout the rest of their studies and experiments into flight. Pictured above is the 1900 glider. Most of their tests with this design were unmanned, with the craft tethered to the ground with ropes.

The Wright Brothers flying their 1901 glider as a kite. Wilbur is on the left and Orville is on the right.

Their next design from the following year, called the 1901 glider, had a much larger wing area, but didn’t produce as much lift as the brothers hoped it would. This lack of lift sent them back to the drawing board. They abandoned full-scale prototypes in favor of small wind tunnel experiments, and ran extensive tests to determine how to balance the lift and drag forces on a wing. These experiments produced a wealth of valuable data, and led to the discovery that longer, narrower wings were much better at creating lift than shorter and wider wings.

Wilbur Wright piloting the Wright Brothers’ 1902 glider. This was the Wright Brothers’ first glider design capable of carrying a person.

Their next glider design from 1902 incorporated the lessons learned from the wind tunnel testing, and featured longer, thinner wings and a pair of vertical rudders at the rear. Pictured above, they made several manned flights with the 1902 glider, but ran into problems with crosswinds. They further developed this design and made over a thousand successful test flights. They were able to control the flight through a three-axis control system. First, lateral motion, or roll, was controlled by wing-warping. Second, vertical motion, or pitch, was controlled by the forward elevator. Third, side-to-side motion, or yaw, was controlled by the rear rudder. This three-axis system of roll, pitch and yaw would go on to become the standard for control in aviation that is still used today.

On 23 March 1903, the Wright Brothers applied for a patent based on their three-axis control system. It was simply titled Flying Machine, and it was based on their 1902 glider design. This was a major milestone in the history of human flight, and it marked the first time a complete system of flight controls were developed and tested successfully. Because of this, some believe this design to be the first ever example of an airplane. Pictured below is a drawing from the 1903 patent, which was granted three years later.

The Wright Brothers’ famous patent for their three-axis control system and their 1902 glider design.

Once they achieved full control of their flights, the Wrights shifted their focus to the problem of power. They had already solved the problem of lift with their previous glider designs, and now they needed to focus on drag. Put simply, a machine will be capable of flying under its own power if it produces enough forward thrust to overcome the drag created by the machine itself. In order to achieve this, the Wrights built a gasoline engine and twin propellers, which they mounted on their glider. This design would come to be known as the Wright Flyer, and as described above it would make the first-ever powered flight of a manned heavier-than-air craft. The flight was one of four that took place on 17 December 1903. Each flight took off from level ground and flew roughly 3 meters (10 feet) above the ground. After the fourth flight, a gust of wind caught the craft and flipped it over several times, damaging it beyond repair. This version of the Wright Flyer would never fly again.

Photo of the Orville Wright piloting the Wright Flyer II aircraft on November 16, 1904.

After the successful flights at Kitty Hawk, the brothers decided to move their operation to Huffman Prairie near Dayton, Ohio. Once there, they built the Wright Flyer II, which improved on the previous design but had trouble flying due to lighter winds at the new location. They eventually found success, however, and achieved the first-ever circular flight on 20 September 1904. Pictured above is the Wright Flyer II in mid-flight with Orville in the pilot seat. The Wright Flyer II made over 100 flights and racked up roughly fifty minutes of flight time before becoming so battered that the brothers decided to scrap it and build a new model.

Photo of the two-seat Wright Flyer III, which was a modified version of the Wright Flyer II from 1905. The brothers tested this craft at Kitty Hawk in 1908.

Pictured above is the Wright Flyer III, which was built in 1905. It performed nearly the same as the previous versions, and after a few crashes the brothers rebuilt it with some modifications. For the new version, they separated the controls for each of the three axes, which greatly improved stability during flight. Now the roll, pitch and yaw had independent controls, and the Flyer could remain airborne for much longer. On 5 October 1905, the Wright Flyer III achieved their longest flight yet, with a distance of 39.4 kilometers (24.5 miles) in just over 38 minutes. This would be the last of the Wright Flyers that the brothers built and tested.

The Wright Brothers were notoriously secretive about their knowledge and designs. They weren’t wealthy or government-funded, and the money for their experiments was still coming from their bicycle business. They believed they needed to build a practical and marketable airplane that they could sell in order to fund further research. This meant they couldn’t share their ideas or prototypes with anyone until they successfully sold them. This secretive stance led to the Brothers filing multiple patents over the years, and opening litigation against others who they felt stole their ideas. As a result, they declined opportunities for marketing and refused to make public or private demonstrations of their Flyers.

This secrecy created tension in their professional relationships, most notably with Octave Chanute, who believed in a free and open exchange of ideas. It also created skepticism from the public over their claims to flight, but it did little to dissuade the Wrights from keeping their designs closely guarded. They went on to file several lawsuits, most notably with Glenn Curtiss, over alleged patent violations. They ended up winning this lawsuit, but their public image was damaged and they eventually ceased corresponding with Chanute because of it.

Photo of Orville Wright with the Wright Model A airplane at the Tempelhof Field in Berlin in September 1909.

The Wright Brothers were the first humans to achieve powered flight, and in so doing they realized a human dream that had lived in our species since our inception. It ushered in the age of the airplane, and it fundamentally changed our relationship with verticality. Events like the this are easily thought of as isolated acts, but in reality they’re just a single chapter in a much larger story. It’s true that the Wrights and their Flyer marked the first time in history that humans could escape the earth’s surface through our own power, but it wouldn’t have been possible without all the time and effort put forth by those who came before them. Their work can be directly linked to other prominent pioneers of flight, such as Octave Chanute, Otto Lilienthal and Sir George Cayley. This network of pioneers can be traced back all the way back to antiquity, and it goes to show just how deeply rooted the human need for verticality goes.

Read more about other ideas for flying machines here.