Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

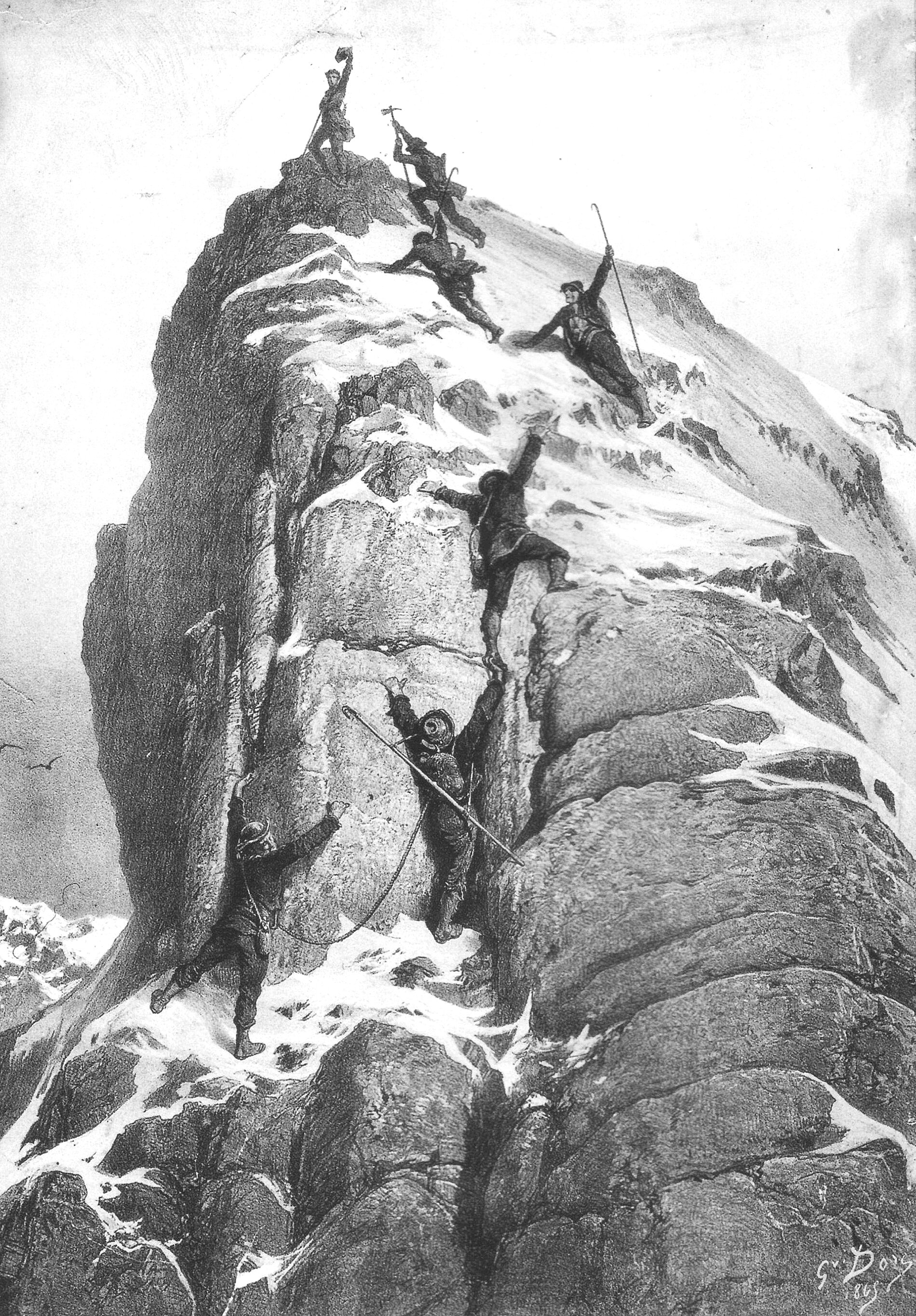

The First Ascent of the Matterhorn

There are few mountains in the world as instantly recognizable as the Matterhorn. Located in the Swiss Alps, this majestic pyramid of gneiss straddles the border between Switzerland and Italy and looms over the Swiss mountain town of Zermatt. Due to its location and visibility, it is legendary within the history of mountaineering . In the 1860’s it was the focus of an international competition to be the first to reach its summit. This story, which includes the first successful summit of the mountain, is a tale of triumph and tragedy, and it serves as a cautionary tale for mountaineers to this day.

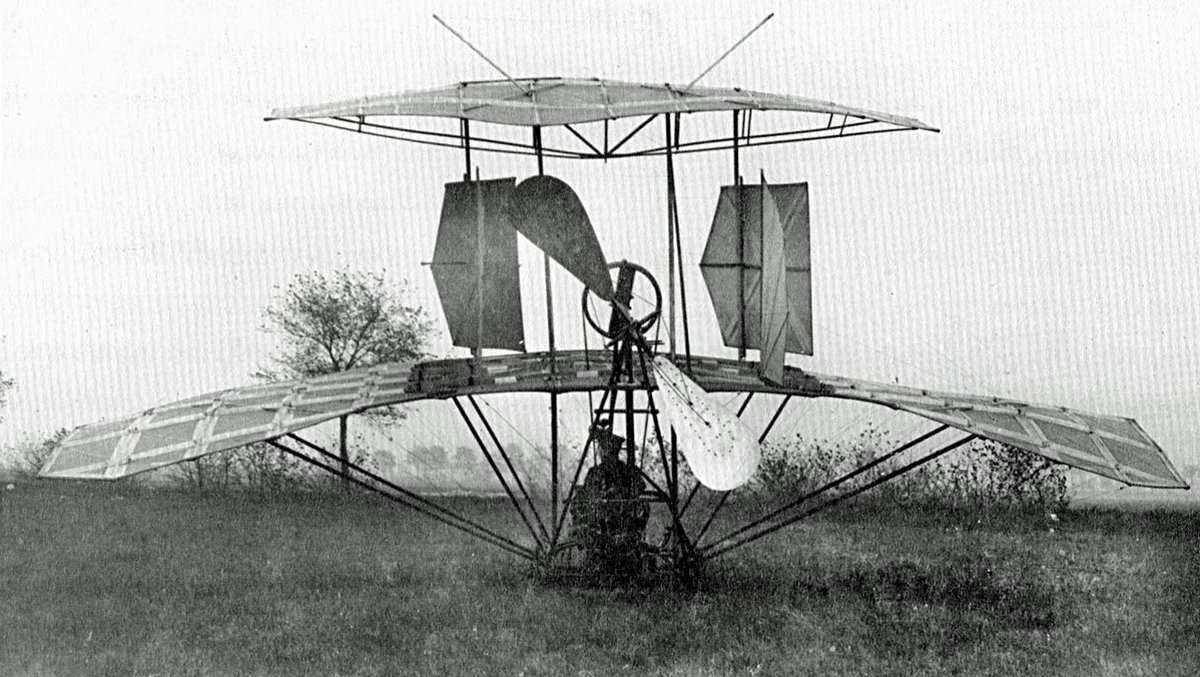

The Jatho Biplane and a Challenge to the Wright Brothers

Pictured above is the Jatho Biplane, built in 1903 by the German aviation pioneer Karl Jatho. During 1903, Jatho made a series of low flights with his machine outside Hanover, Germany. These flights took place a few months before the Wright Brothers achieved powered, controlled flight. We don’t know for sure if the Jatho Biplane was controlled, however. If it was, that means the Wright Brothers weren’t the first to achieve flight. If it wasn’t, the Jatho Biplane is just another prototype that got close, but didn’t actually achieve flight.

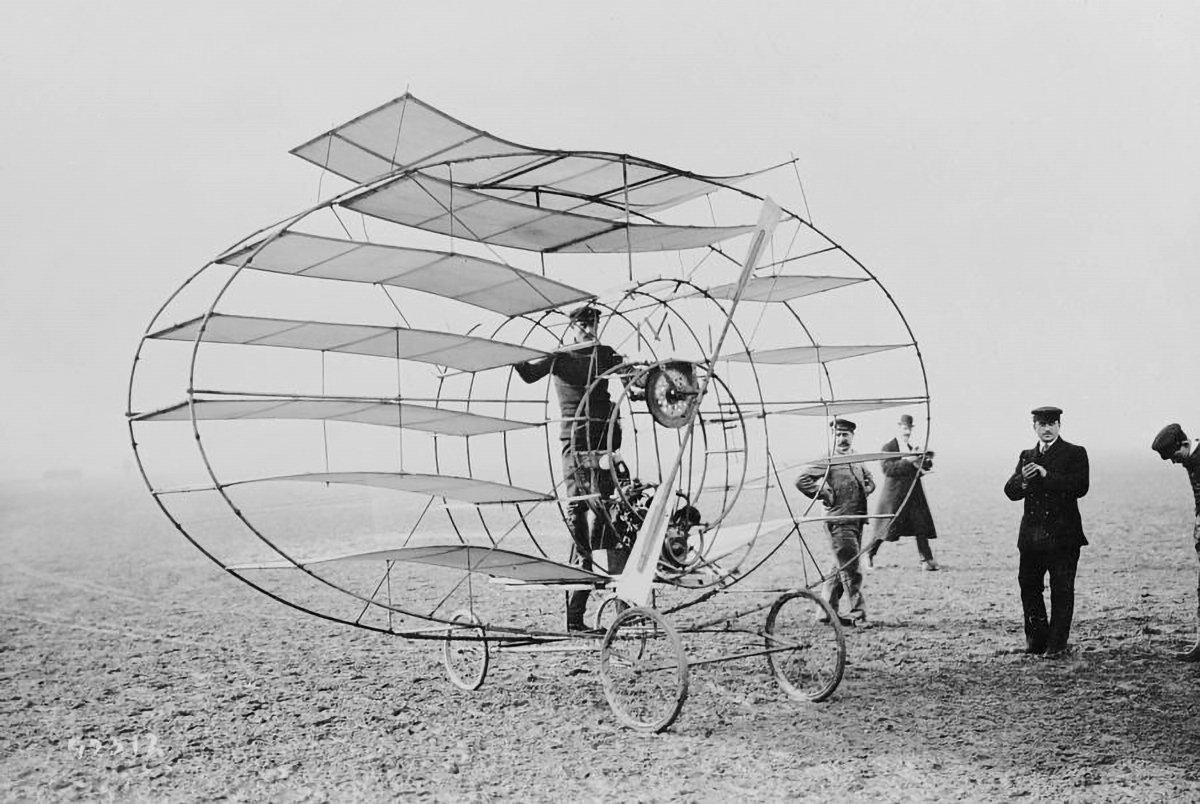

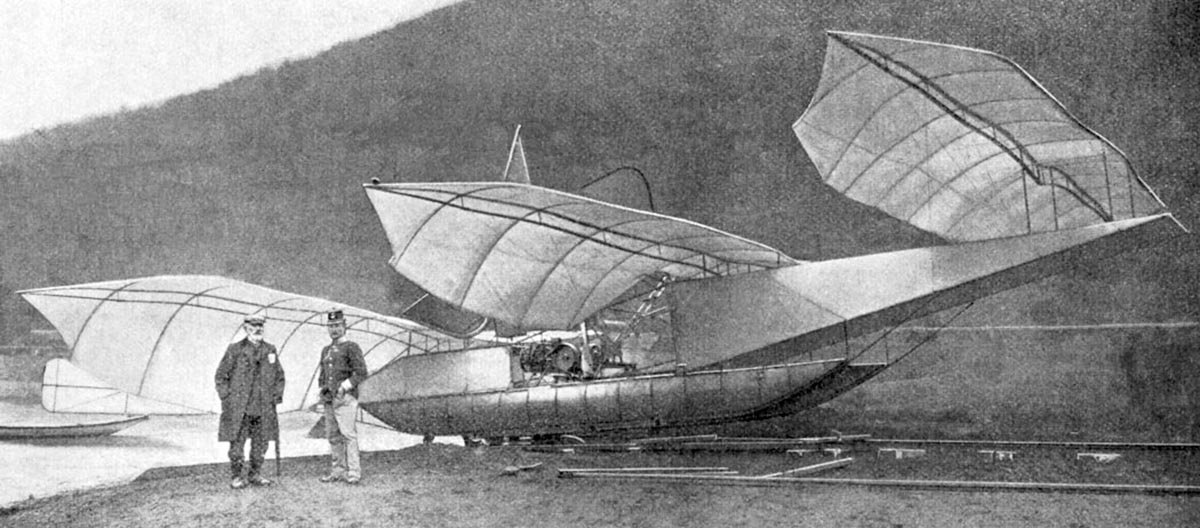

The Marquis Multiplane

If two wings can provide enough lift to make an aircraft fly, surely adding more wings must make it fly even better, no? It’s a silly question by today’s standards, but in the early days of flight it was a legitimate inquiry to be studied. One man who decided to test the theory was Marquis d'Ecquevilly, and pictured above is the Marquis Multiplane which he designed in 1908.

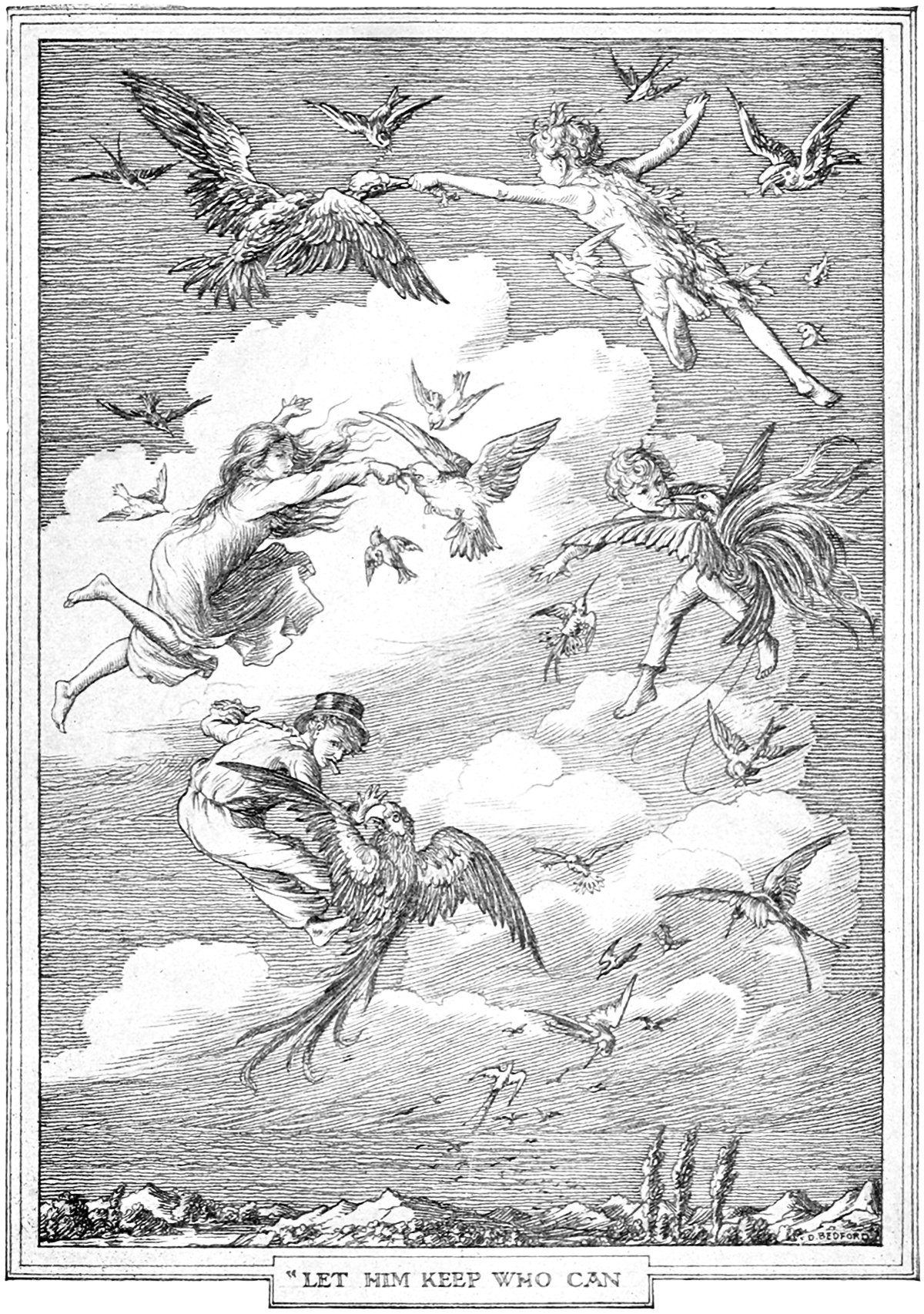

Peter Pan and the Delights of Flying

Peter Pan is perhaps best known from the animated 1953 film Peter Pan, but his story originated in the book Peter and Wendy, written in 1911 by J. M. Barrie. It’s a story of fairies, mermaids, pirates, and a mischievous boy with the power of flight. This boy, named Peter Pan, has adventures in Neverland with a group of British children that he teaches to fly. Flight is central to the narrative of the story, and Barrie does a good job of describing the children’s joy as they learn to fly.

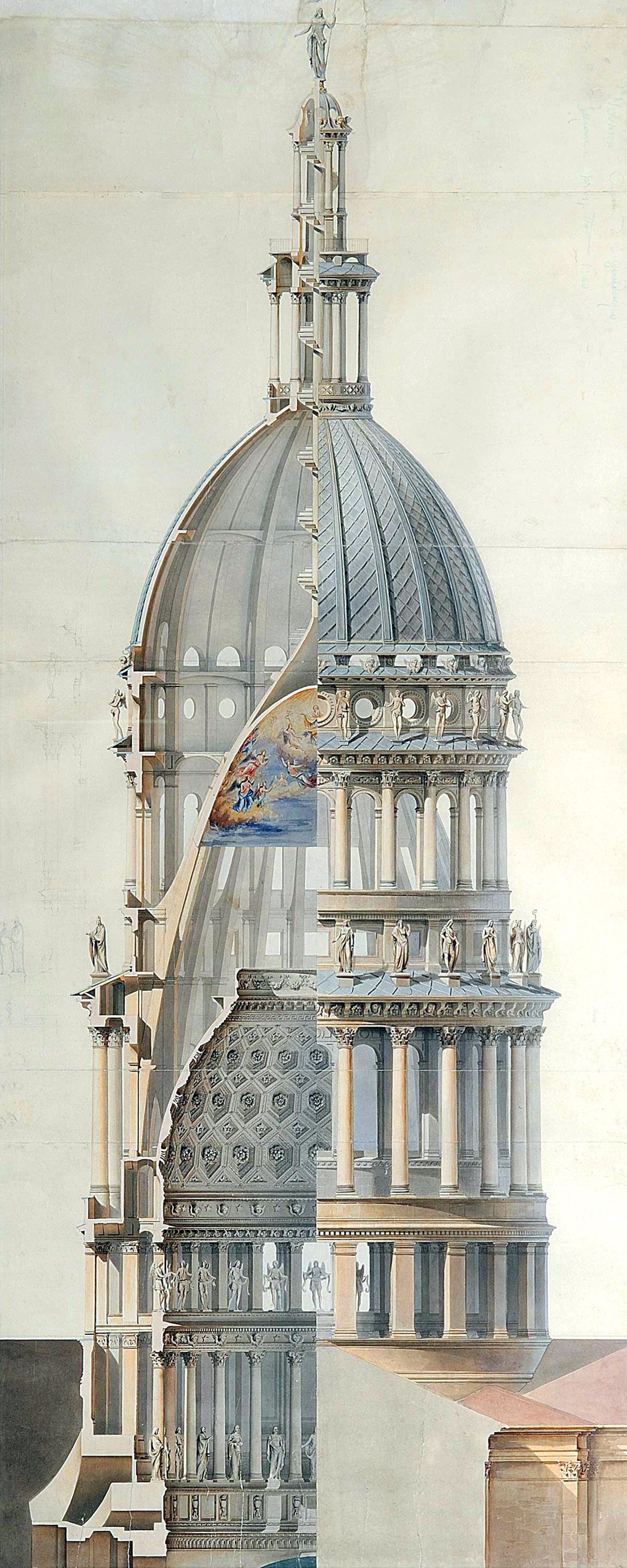

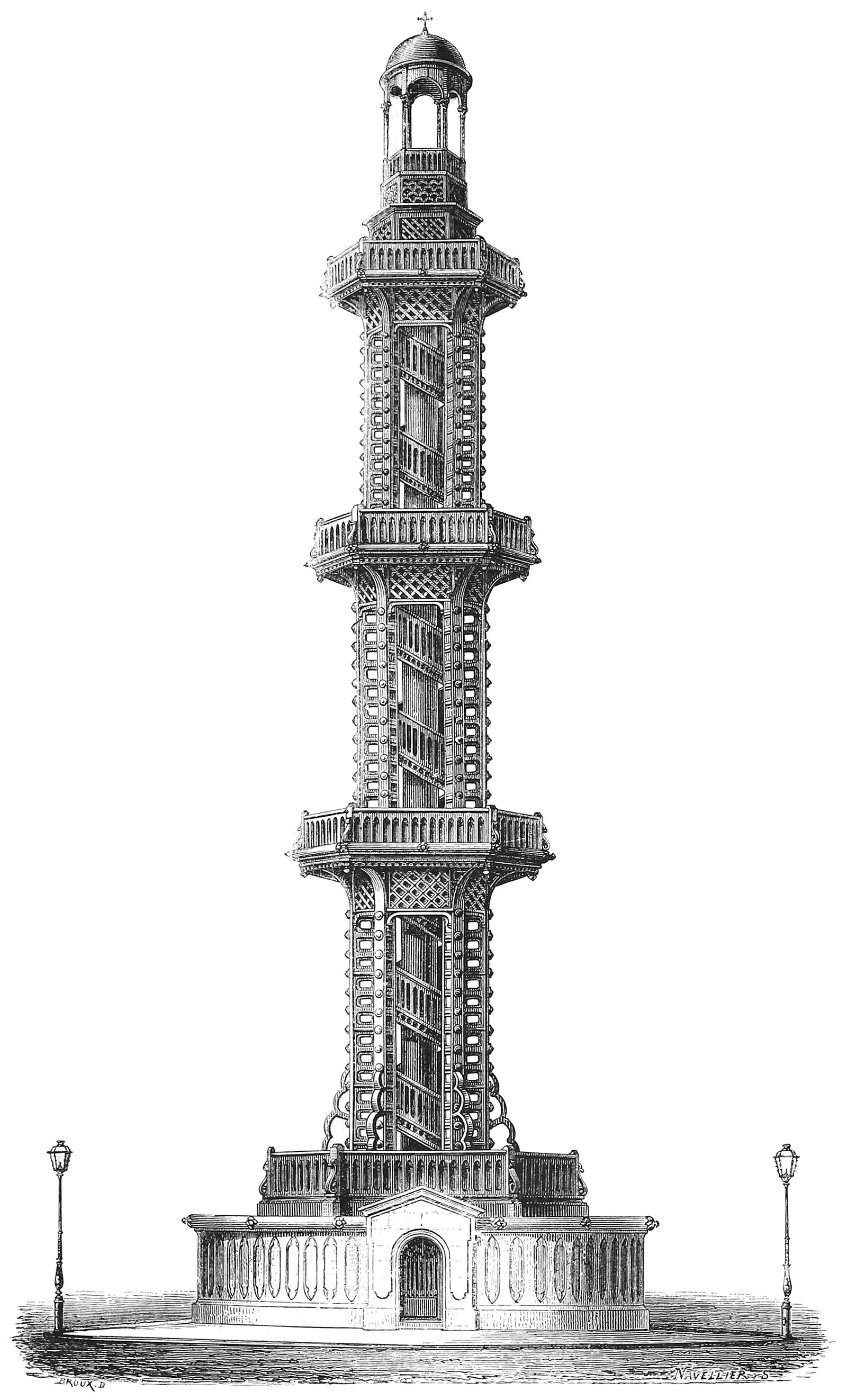

Alessandro Antonelli’s Basilica of San Gaudenzio

Pictured above is an elevation of the Basilica of San Gaudenzio in Novara, Italy. The building features an elaborate dome and cupola structure. This structure appears to be on steroids, with quite a few stacked-forms below and above the dome itself. It seems over-built compared to the building it caps, and it’s overtly vertical design is a statement from the architect regarding the power of verticality.

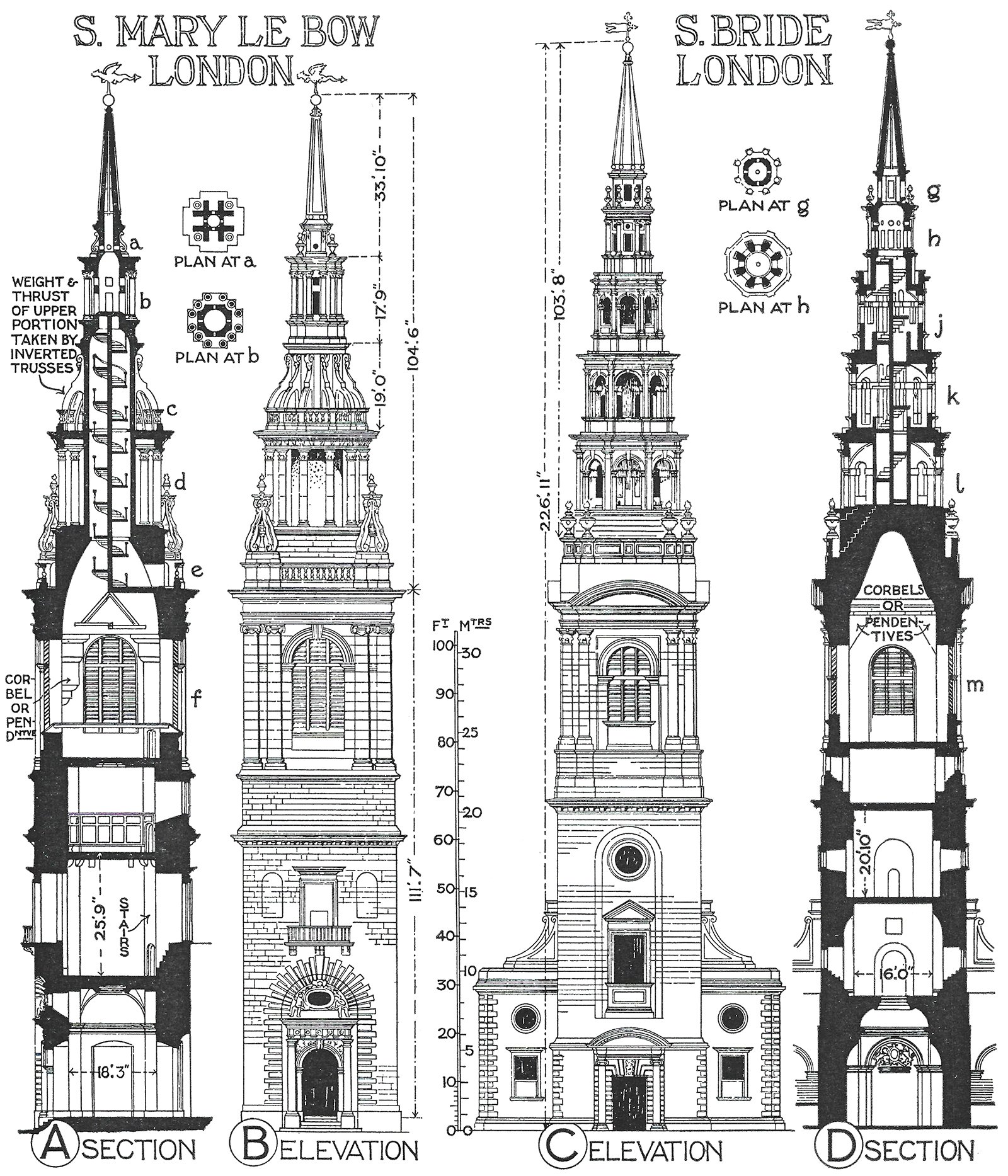

Sir Christopher Wren’s Church Steeples

Sir Christopher Wren was an English architect best known for his Renaissance and Baroque church designs that commonly featured conspicuous steeple designs. Pictured above are drawings of two such examples. These steeples are massive in scale, and they dwarf their adjacent church buildings. This mismatch of scales suggests that Wren considered these towers to be much more important than the churches they accompany. Through their height, Wren was using verticality to announce the presence of his buildings.

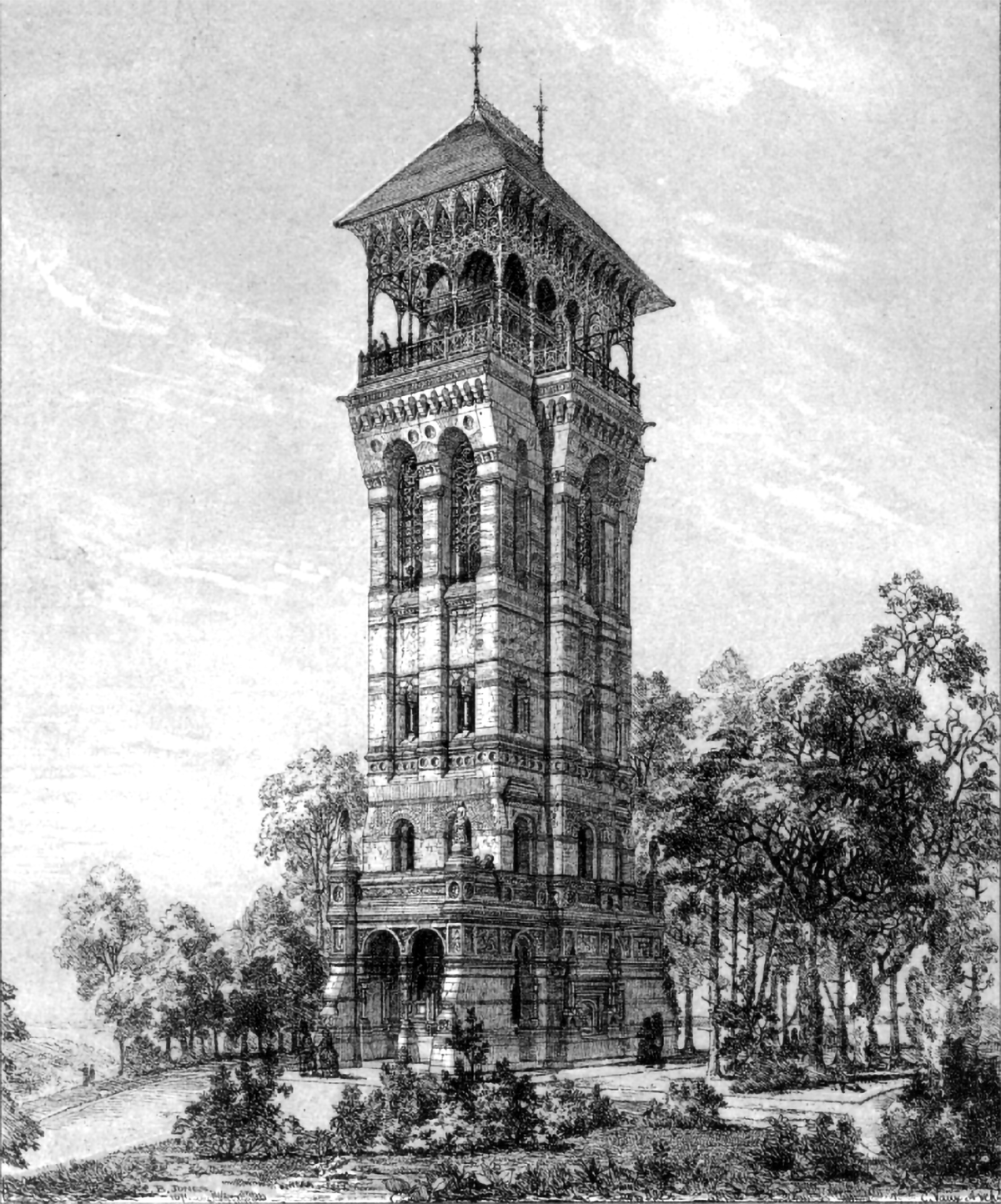

A Proposal for an Observation Tower in Prospect Park

Prospect Park in Brooklyn is one of the great examples of landscape architecture in the United States. It was designed by the legendary landscape architects Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux and was completed between 1867 and 1873. The original design included an observation tower at the highest point in the park, which is pictured above. Unfortunately, it never got built.

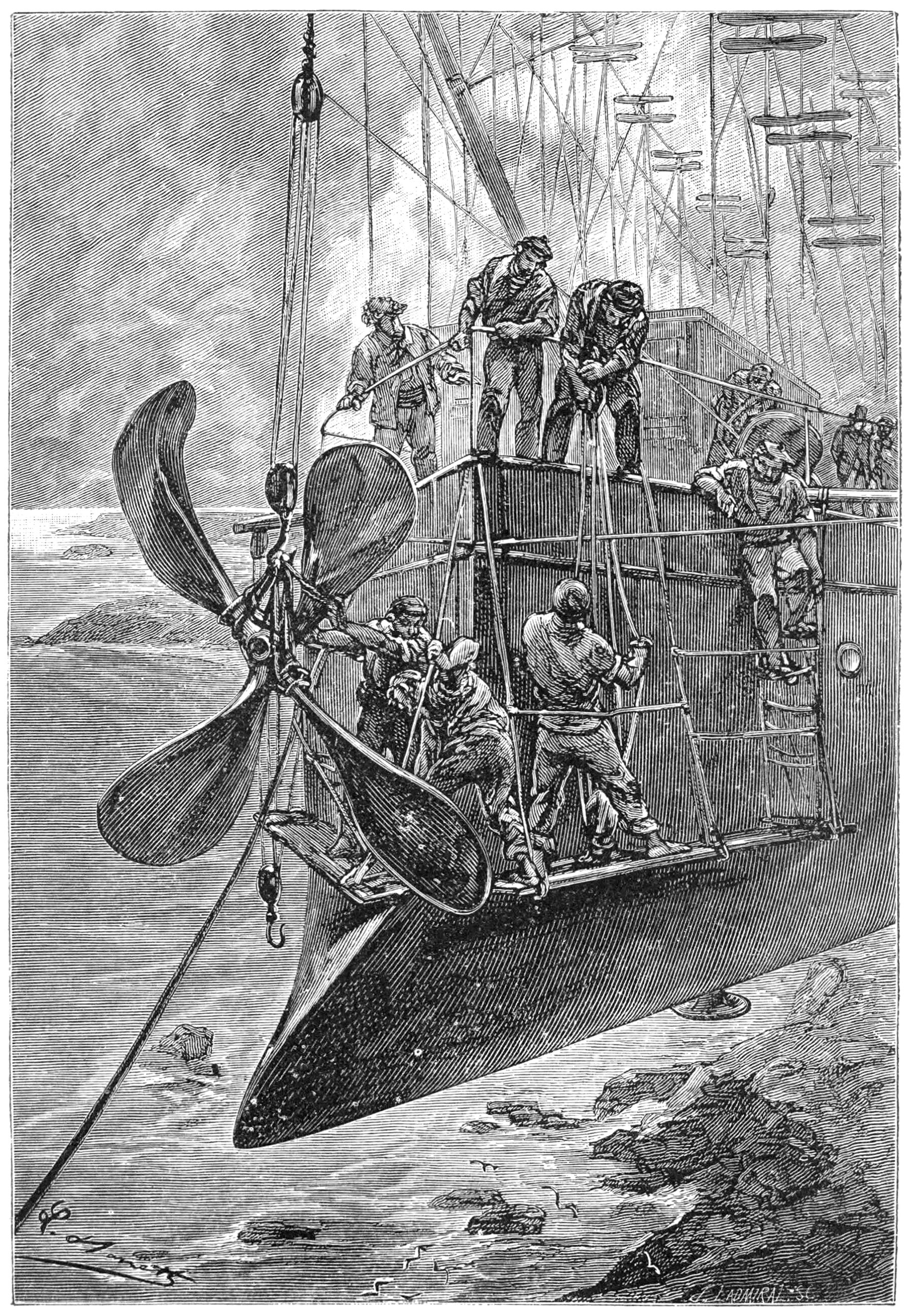

Jules Verne’s Clipper of the Clouds

Fiction has a way of reflecting and informing reality. Pictured above is an illustration from Jules Verne’s novel Robur the Conqueror, published in 1886. It shows a fictional flying machine called the Clipper of the Clouds, which was built by the novel’s titular character. Throughout the story, Verne explores the nature of flight, its effects on humanity, and the general sense of public awe in the early days of flying machines. There’s also an undertone of the God versus Ego struggle that is central to the verticality narrative.

Wilhelm Kress’ Drachenflieger

Pictured above is the Drachenflieger, which was an experimental aircraft designed in 1901 by Austrian engineer Wilhelm Kress. It’s name means Dragon Flyer in German, and it was an attempt by Kress to build the world’s first heavier-than-air flying machine. The craft consisted of a central undercarriage and three large pairs of wings, each set at a different height so they wouldn’t interfere with one another. It was meant to take off and land on the water, so Kress designed it to rest on two pontoons.

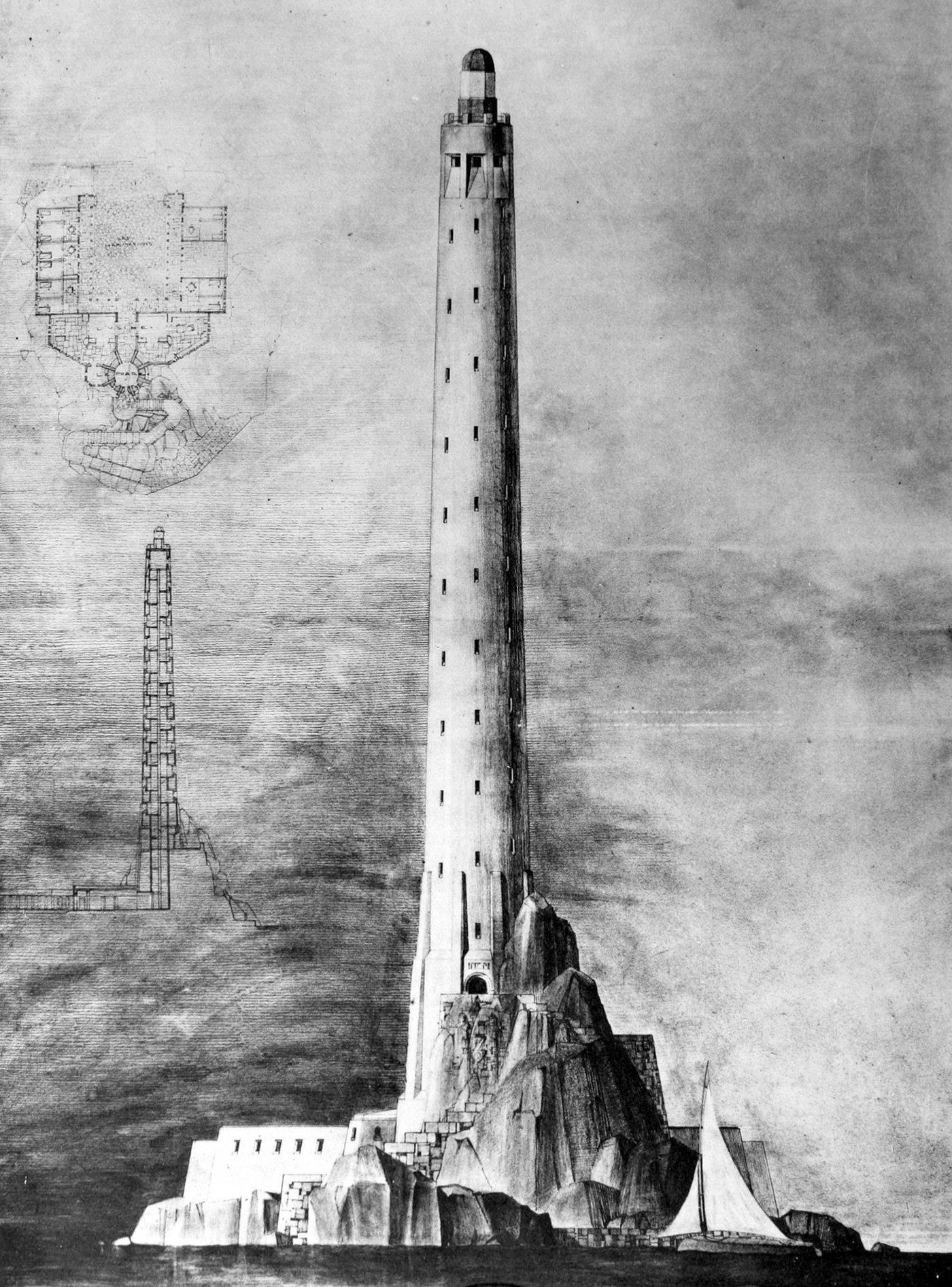

A Proposal for a Monumental Lighthouse

Pictured above is a student proposal for a monumental lighthouse from the École des Beaux-Arts. Designed in 1925, the structure is a tapered cylinder that rises high above the small, rocky island it resides on. As with any lighthouse, height is the main currency here. A higher light source will be visible from a greater distance, which makes the surrounding sea safer as a result.

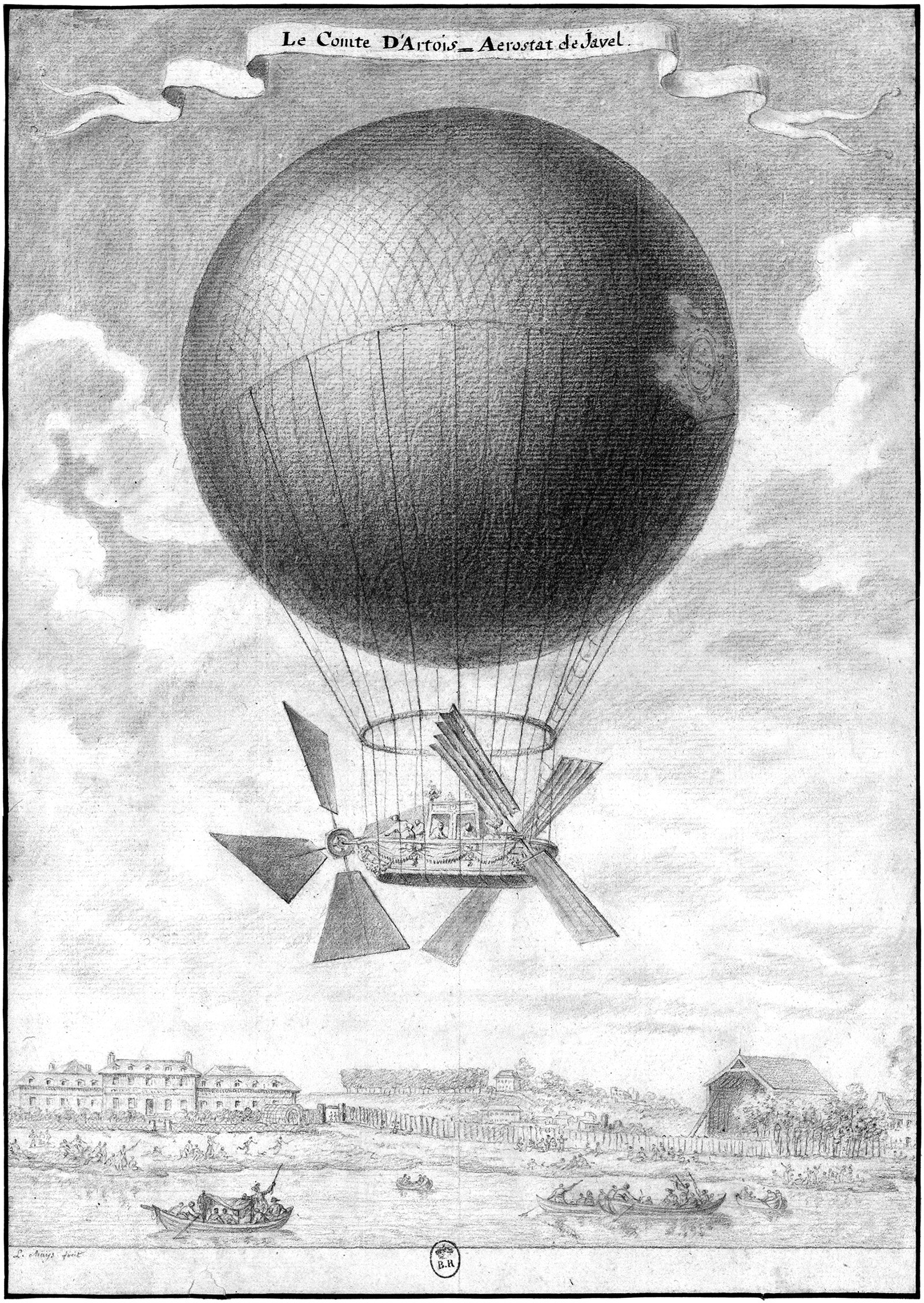

Alban & Vallet’s Comte d’Artois

Pictured above is a design for a flying machine by Léonard Alban and Mathieu Vallet from 1785. It was called Comte d-Artois, or l'Aérostat de Javel. It had a helium-filled balloon which carried a gondola. At one end of the gondola was a large propeller and at the other end was a pair of paddles. The gondola could comfortably seat four people and resembled a shallow boat. Throughout 1785, Alban and Vallet made many successful flights around Paris with the craft, and they also made three notable advancements in ballooning technology along the way.

Richard Pearse and a Claim to the World’s First Powered Flight

Pictured above is a photograph of a monoplane designed and built by Richard Pearse in 1903. Pearse was a farmer who had an interest in engineering, flight and flying machines. He had previously designed bicycles and engines, but in the early 1900s he was working on a design for a flying machine. It was a monoplane with a front-mounted propeller and a large wing constructed of a bamboo frame and canvas.

The Towers of Svaneti

Joseph Campbell once said that you can tell what’s informing a society by what the tallest building is. The Towers of Svanetia are a perfect example of this. Svanetia is a mountainous region in Georgia dotted with small, medieval villages. These highland villages are home to a unique type of tower house, which gives us a window into the history and culture of the region. Pictured above is an illustration of one such village and its towers.

The Grenelle Artesian Well of Paris

Pictured above is the Grenelle Artesian Well in Paris, built from 1834 to 1841. During these seven years, an 8-inch diameter hole was drilled to a depth of roughly 550 meters (1,800 feet) below the earth’s surface. This process of construction took place far below ground, but in the end the well was marked with a 42 meter (138 feet) tower and fountain, placed a block away from the well itself. The tower was a deft mixture of uses, including a fountain, a sculpture, and an observation deck.

The Wright Flyer and the World’s First Powered Flight

Upon a flat plain outside the town of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903, a home-made flying machine lifted off the ground into a headwind. It landed twelve seconds later and 37 meters (120 feet) away from its launch point. This short distance marked the first time in the history of humankind that a manned, heavier-than-air craft had flown under its own power. This event would cement its creators into the pantheon of technological pioneers and make them a household name.

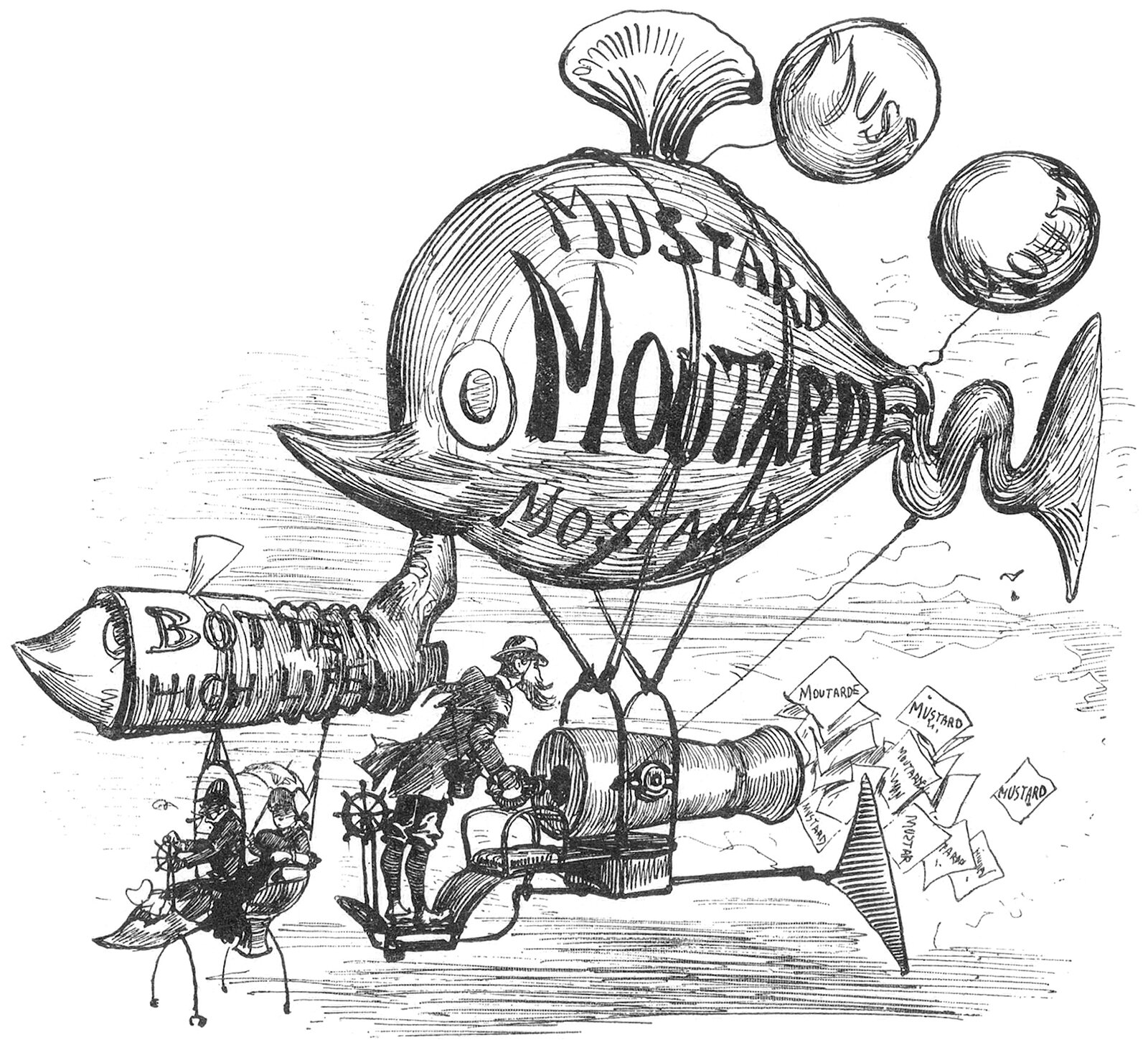

Albert Robida’s Flying Advertising Machines

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. The novel describes a future vision for Paris in the 1950’s, focusing on technological advancements and how they affected the daily lives of Parisians. Here, he shows a pair of flying machines meant for advertising.

The Évreux Belfry

Pictured above is an illustration from 1825 showing a streetscape in Évreux, France. It was drawn by Richard P. Bonington, and it focuses on the town belfry, which was built from 1490-1497. Bonington does a great job of showing how a tower like this can dominate a streetscape, even if it isn’t that tall by today’s standards.

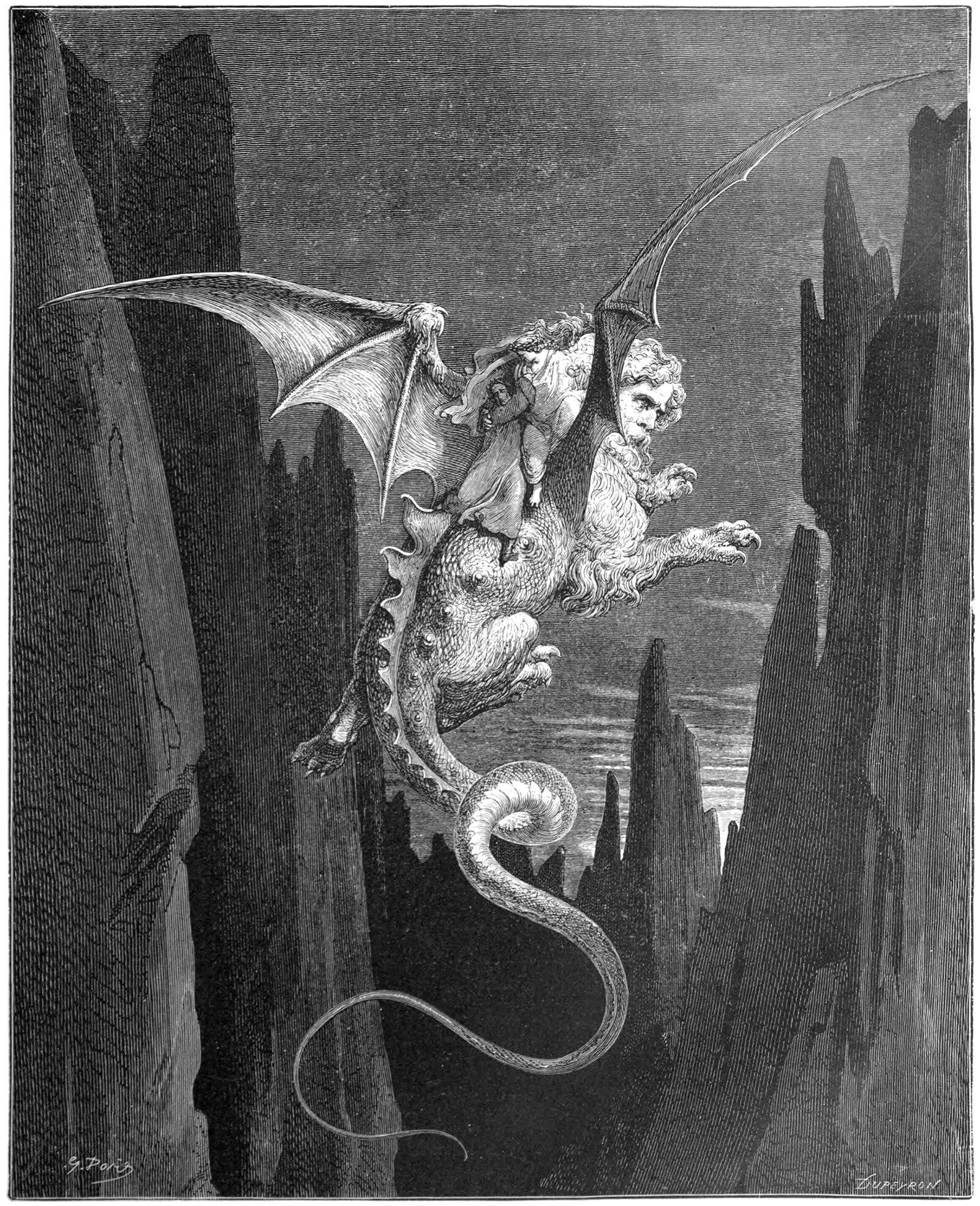

The Flight of Geryon

The above illustration by Gustave Doré shows a scene from Dante’s Divine Comedy. The epic poem follows Dante and Virgil as they pass through Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso, and it deals with the concepts of Heaven and Hell, as well as the Seven Deadly Sins. This scene is from Canto XXVII of Inferno, when Dante and Virgil mount the back of the great beast Geryon and fly down from the seventh to the eighth circle of hell.

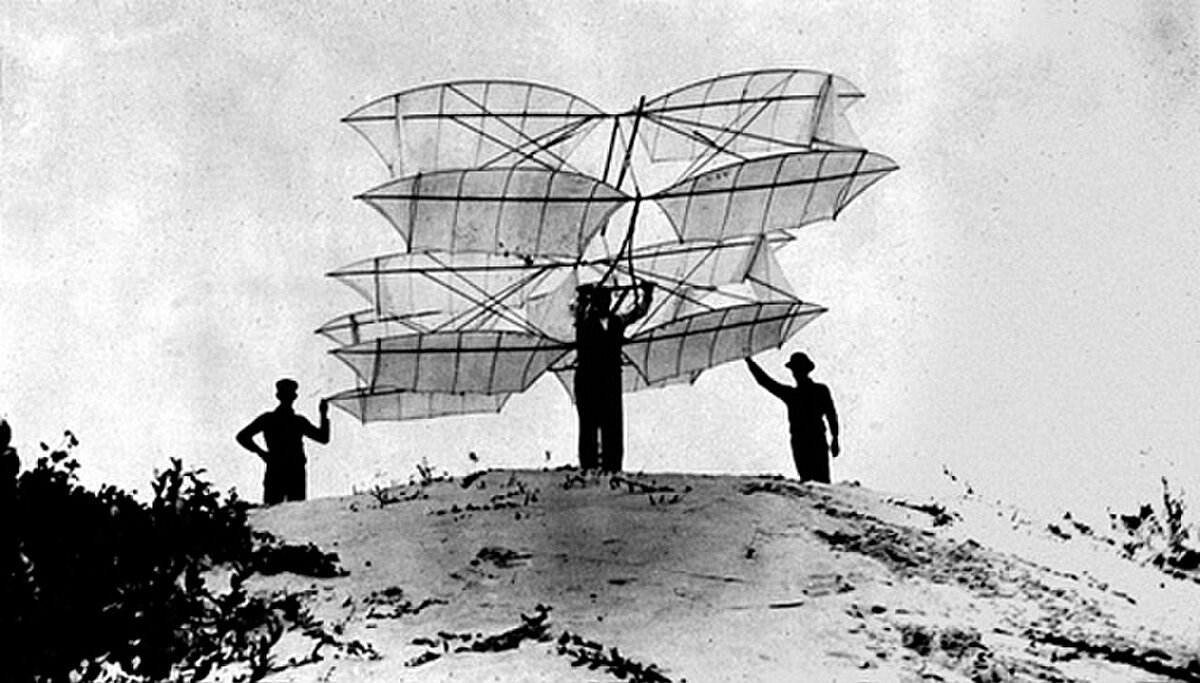

Octave Chanute’s Glider Designs

Pictured above is a twelve-winged glider designed by Octave Chanute in 1896. It’s one of many flying machines Chanute experimented with, and like these others, it directly influenced other pioneers of aviation. Chanute began his career as a civil engineer, and he made a name for himself building railroads and bridges. After retiring in 1883, he turned his attention to aviation, which was a subject he’d been interested in for decades prior.

The Seattle Space Needle and Uninterrupted Verticality

I recently visited the Space Needle while on a trip to Seattle, and the experience was a masterful example of uninterrupted verticality. Throughout the entire visit, I had visual access to my surroundings, and this made the experience much more meaningful than a typical observation tower or skydeck. This is because the lift experience is normally buried deep inside a building, so it doesn’t have views to the outside. This severs the experience of verticality and abstracts the act of ascension and descension. Not the case at the Space Needle, however, and it was fantastic.