Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

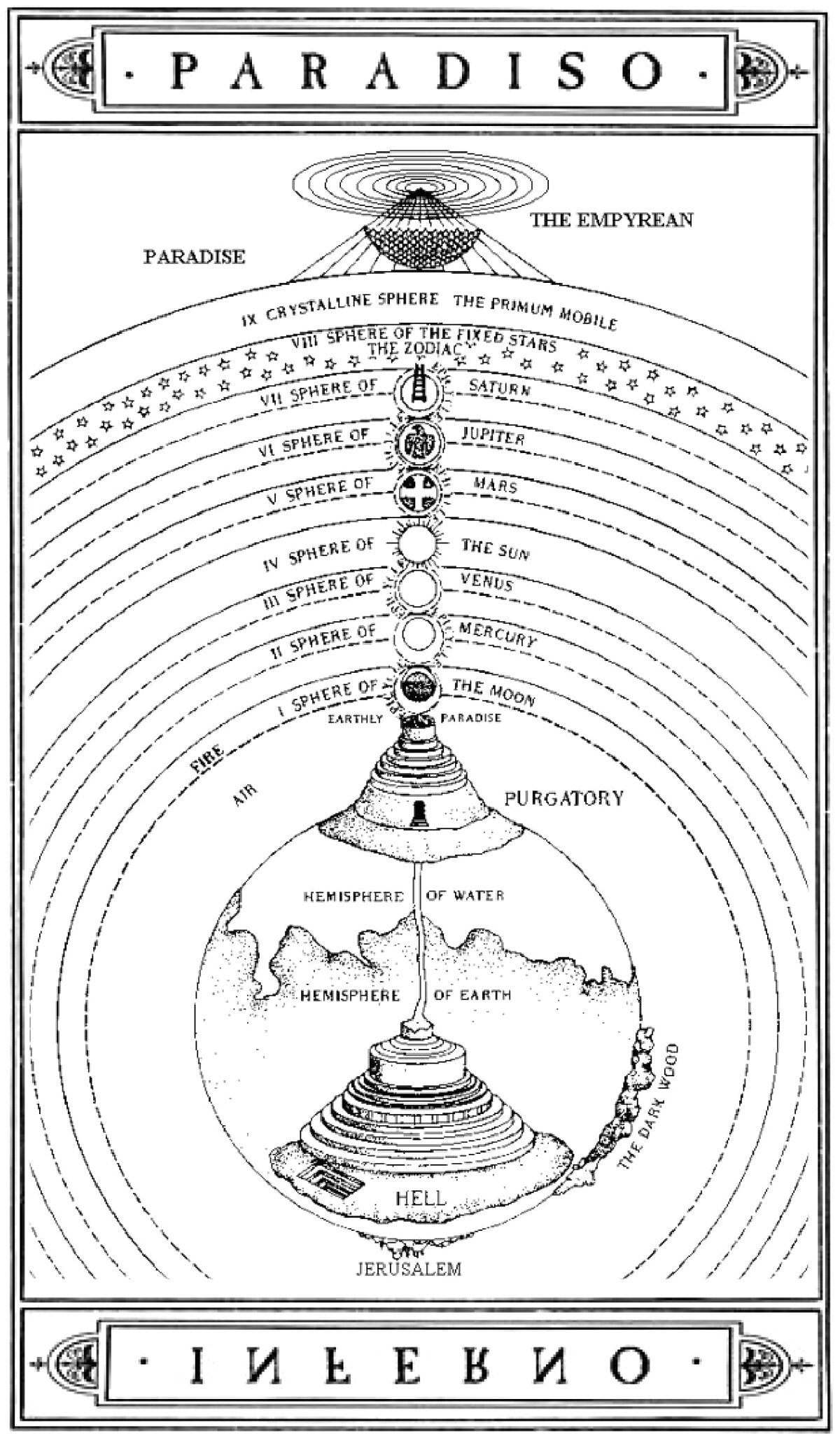

Dante’s Divine Comedy and the Vertical Worldview

Dante Alighieri’s epic poem La Divina Commedia, or The Divine Comedy in English, is widely considered one of the world’s greatest works of literature. It tells the fictional story of Dante and his soul’s experience after death. Throughout the story, Dante descends through Inferno, then ascends through Purgatorio and Paradiso. It’s a journey defined by the axis-mundi, and the entire work is rooted in verticality.

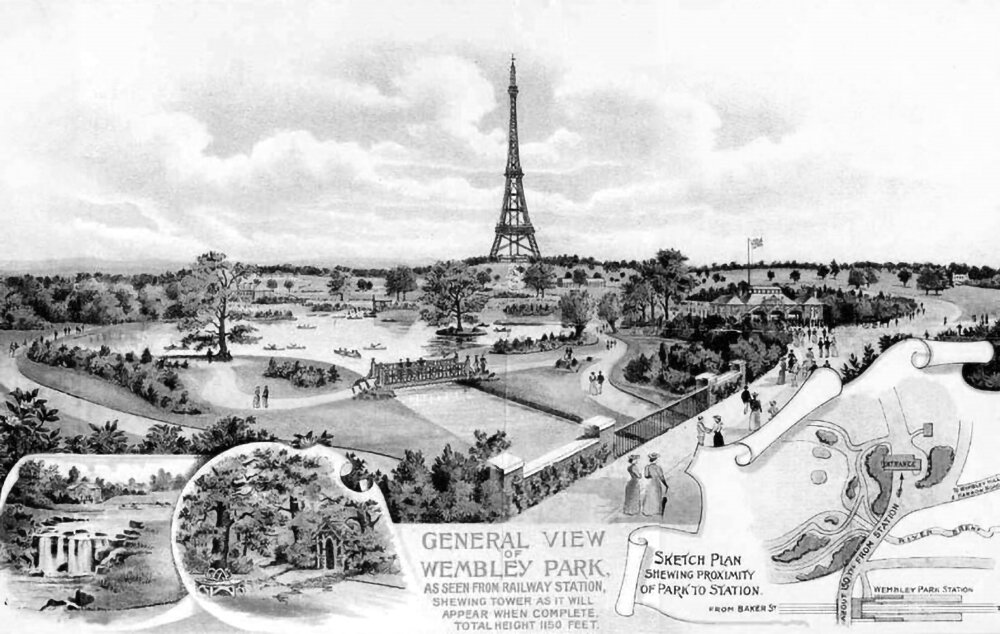

Alternate Realities : The Great Tower for London Competition

In 1890, an open competition was held to design the Great Tower for London in the soon-to-be-opened Wembley Park. The tower was to be the tallest in the world, and it would claim the title from the Eiffel Tower in Paris, completed the year before. An open competition was held, which received 68 submissions from all over the world. Together, these designs provide a rich cross-section of the world’s architectural taste at the time.

Alternate Realities : The Eiffel Tower

There’s an interesting subtext to unbuilt projects throughout the history of architecture. Unbuilt additions to existing buildings are the most intriguing, because they respond to an existing mind-scape rather than create a new one. The above illustration is a perfect example of this. It shows a preliminary design for the Eiffel Tower in Paris, drawn by French architect Stephen Sauvestre.

The Myth of Wayland the Smith

Throughout the history of myths and legends, there are myriad stories that are shared or borrowed from earlier sources, then re-named and adjusted for a different culture. Certain themes repeat themselves throughout the ancient world, and those that resonate most effectively will endure over time and evolve alongside the cultures they exist in. The myth of Wayland the Smith is one of these.

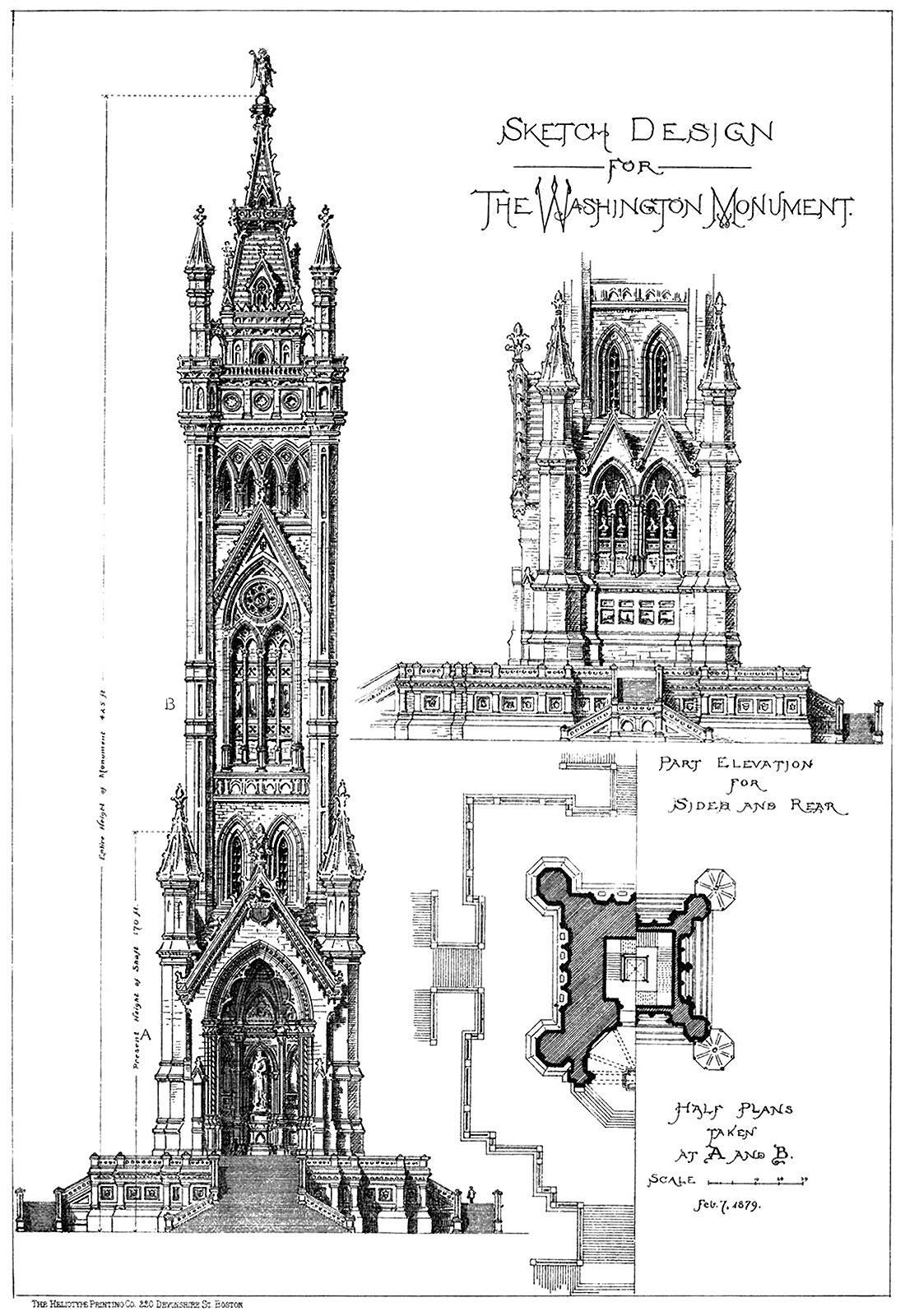

A Sketch Design for the Washington Monument

The above illustration originally appeared in American Architect and Building News, and was submitted to the publication by an architecture student. Curiously, the student is not named, and is just called ‘the author’. The student uses ‘the Gothic treatment’ for the design, which is wonderfully detailed, in stark contrast with the minimalist design that eventually got built.

King Bladud and the Myth of the Flying Man

Legends have a way of expanding through time. They exist in the collective consciousness of the people who believe them, and the ones that endure usually grow and evolve alongside the cultures and civilizations they exist in. Take the myth of King Bladud, for example. Over time his story has expanded and endured. This is because he made an attempt to fly.

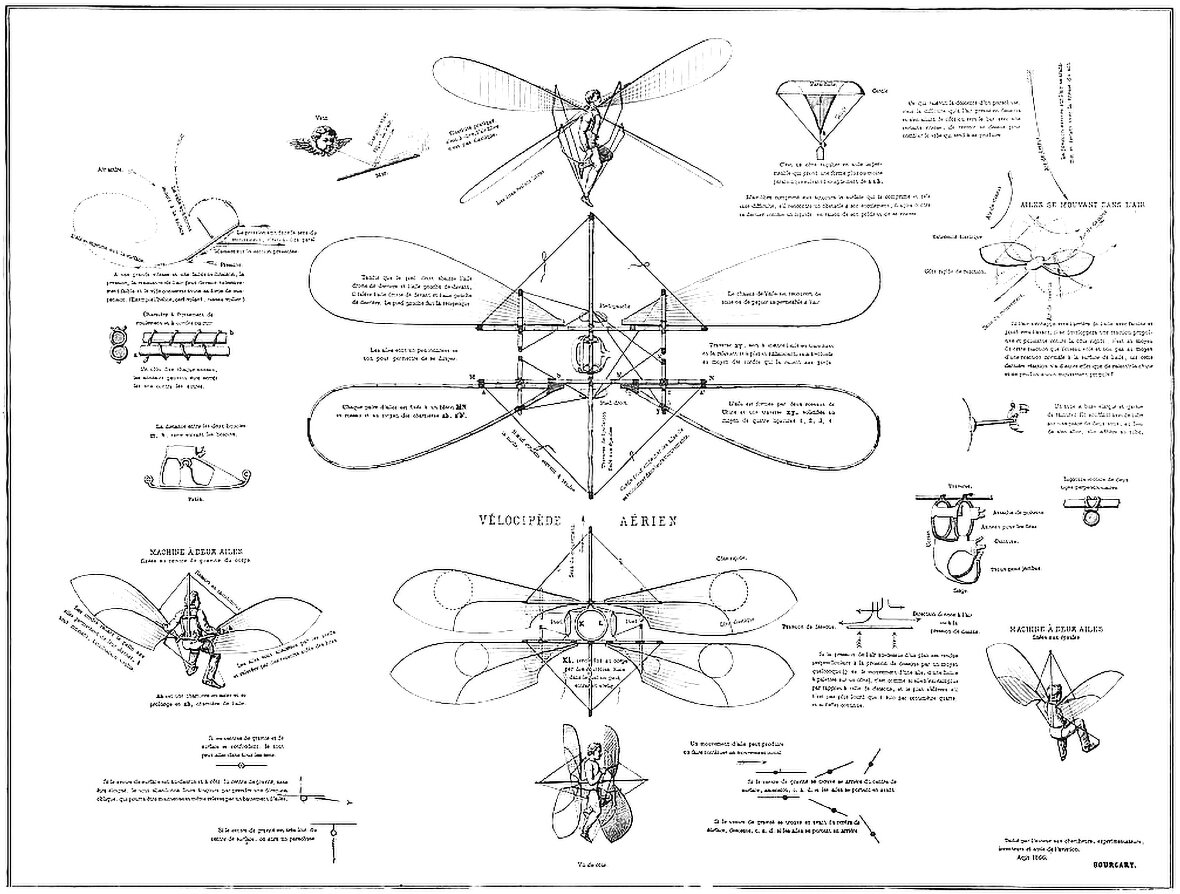

Jean Jacques Bourcart’s Ornithopter

Pictured above is a series of studies for a flying machine, proposed in 1866 by Jean Jacques Bourcart. Titled Vélocipède Aérien, the drawings show variations on an ornithopter design, in which a human pilot flaps the wings of the craft in order to fly. The subtitle of the illustration reveals that these are studies, tests and inventions which, without solving the problem of aviation, have nevertheless given interesting and encouraging results to the author.

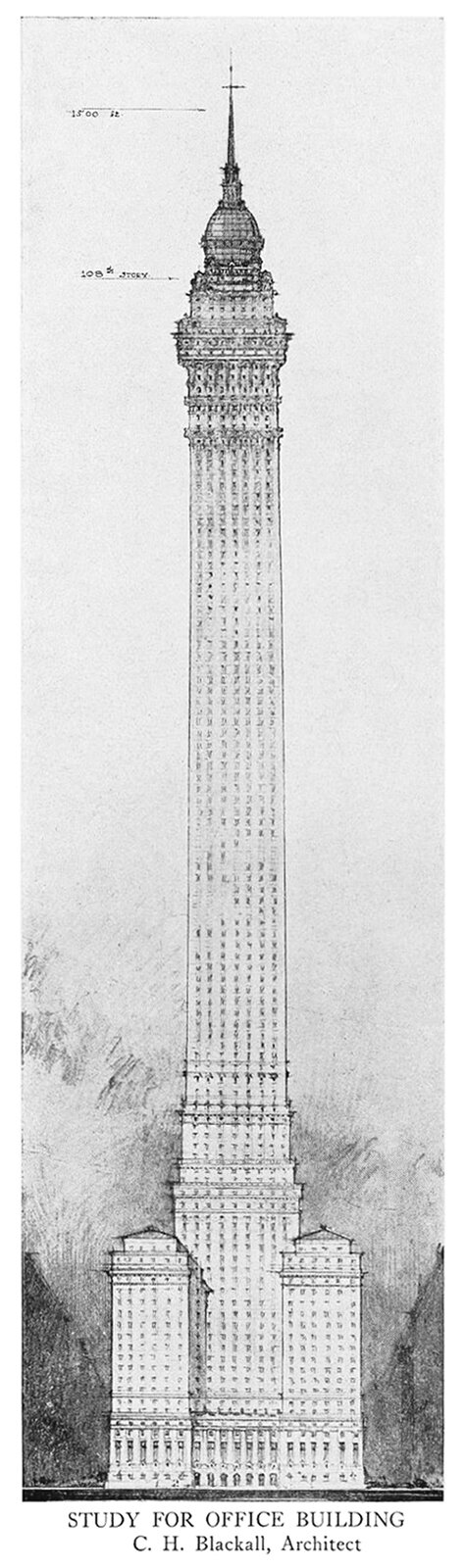

Clarence H. Blackall’s Study for an Office Building

The above illustration originally appeared in an exhibition for the Boston Architectural Club in 1912. The subsequently published yearbook containing the drawing gives no context or background, just the cryptic title Study for Office Building and the architect’s name, Clarence H. Blackall.

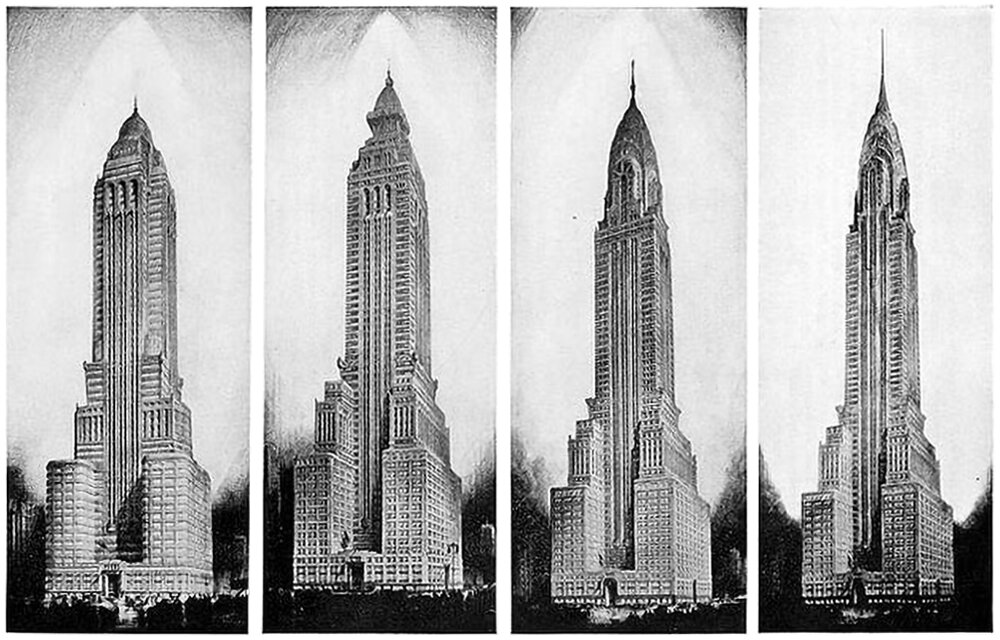

Alternate Realities : The Chrysler Building

The design process is never-ending. The only reason there’s an end is because something needs to get built, and it usually needs to happen quickly. It’s like a film, and the built result is like a snapshot from somewhere near the end of the film. .e image for example, showing. The above illustration is a good example. It four proposed designs for the Chrysler Building in New York.

Louis Charles Letur’s Parachute-Glider

Pictured above is an 1853 design for a flying machine by German engineer Louis Charles Letur. His design consisted of a pilot’s basket flanked by two triangular wings, along with a vertical tail behind (not pictured in the above illustration). This assembly would hang under a large umbrella-like parachute, and it was meant to be lifted to a height by some other means, such as a balloon, then it would glide safely back down to earth.

Daedalus and Icarus : A Parable of Human Flight

The oldest and most storied myth of human flight is the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Any history of flight, if tracked back far enough, will find it’s inception rooted in this timeless tale of youthful hubris. Over the centuries, the name Icarus has become synonymous with over-ambition, and has inspired countless other stories relating to human flight.

Nicolas Edme Rétif’s Flying Man

The above illustration is from Nocolas Edme Rétif’s 1781 novel La Découverte Australe par un Homme-Volant, or The Discovery of the Austral Continent by a Flying Man. The fictional bird suit pictured was built by Victorin, the main character of the novel. He was in love with the daughter of a local lord, and he built a flying suit in order to kidnap her and fly her to the summit of a local mountain, where no people could reach.

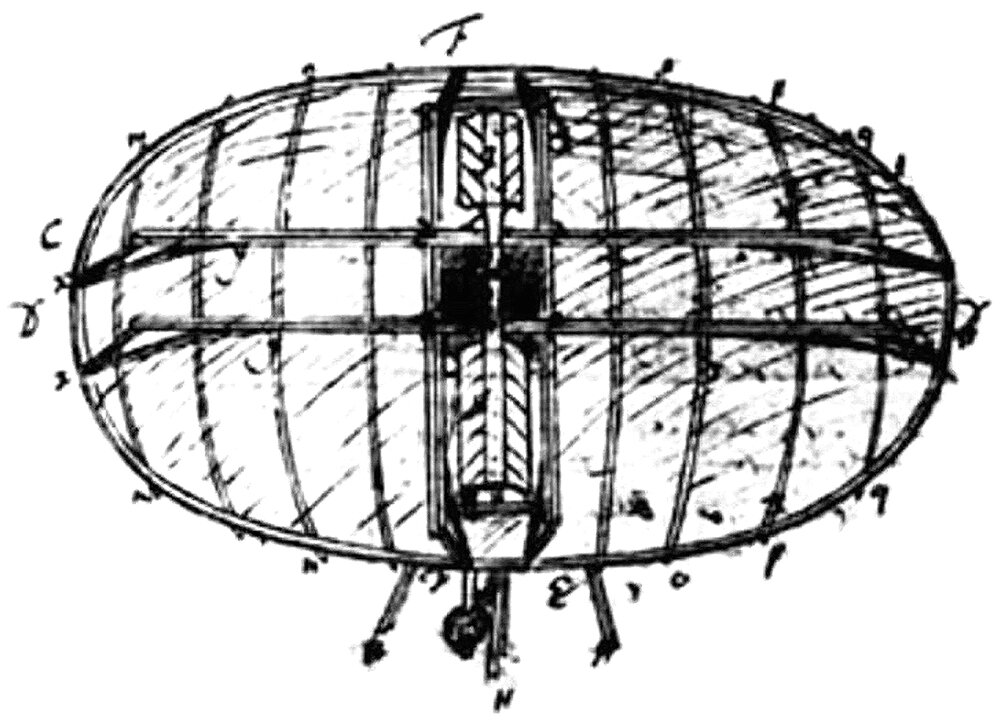

Emanuel Swedenborg’s Glider Sketch

The earliest examples of flying machines are from one of two sources. The first are fictional sources, such as myths or epics, and the second are exploratory sketches from great thinkers of their time, such as Leonardo da Vinci. The sketch above is an example of the latter, and it was sketched in 1714 by Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish polymath known for his theological works. The design is a combination of a glider and an ornithopter, and he sketched it in one of his notebooks with full knowledge that it could never fly.

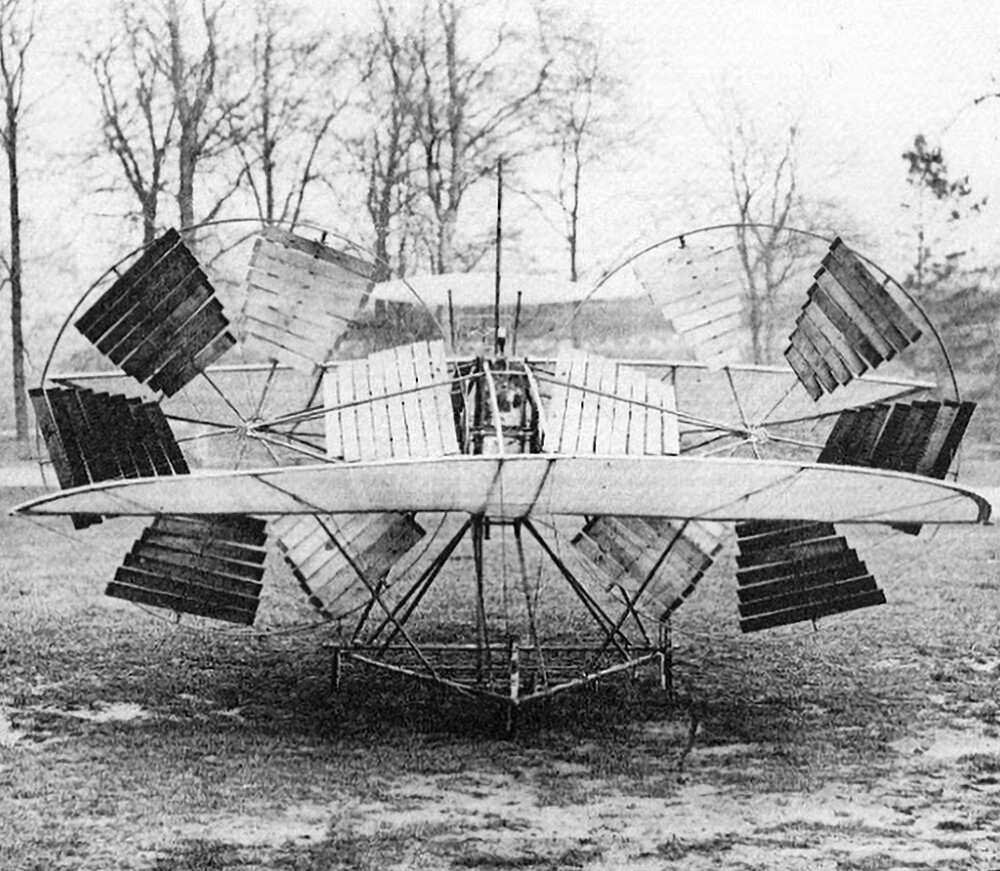

Thomas Moy’s Aerial Steamer

Pictured above is Thomas Moy’s 1875 design for a flying machine, called the Aerial Steamer. It’s an unmanned tandem wing aircraft, with two pairs of wings: one pair at the front and one pair at the rear. Between the two pairs of wings were two massive propellers, which were made of wooden slats in a helix-like pattern that was designed to provide upward and forward lift simultaneously.

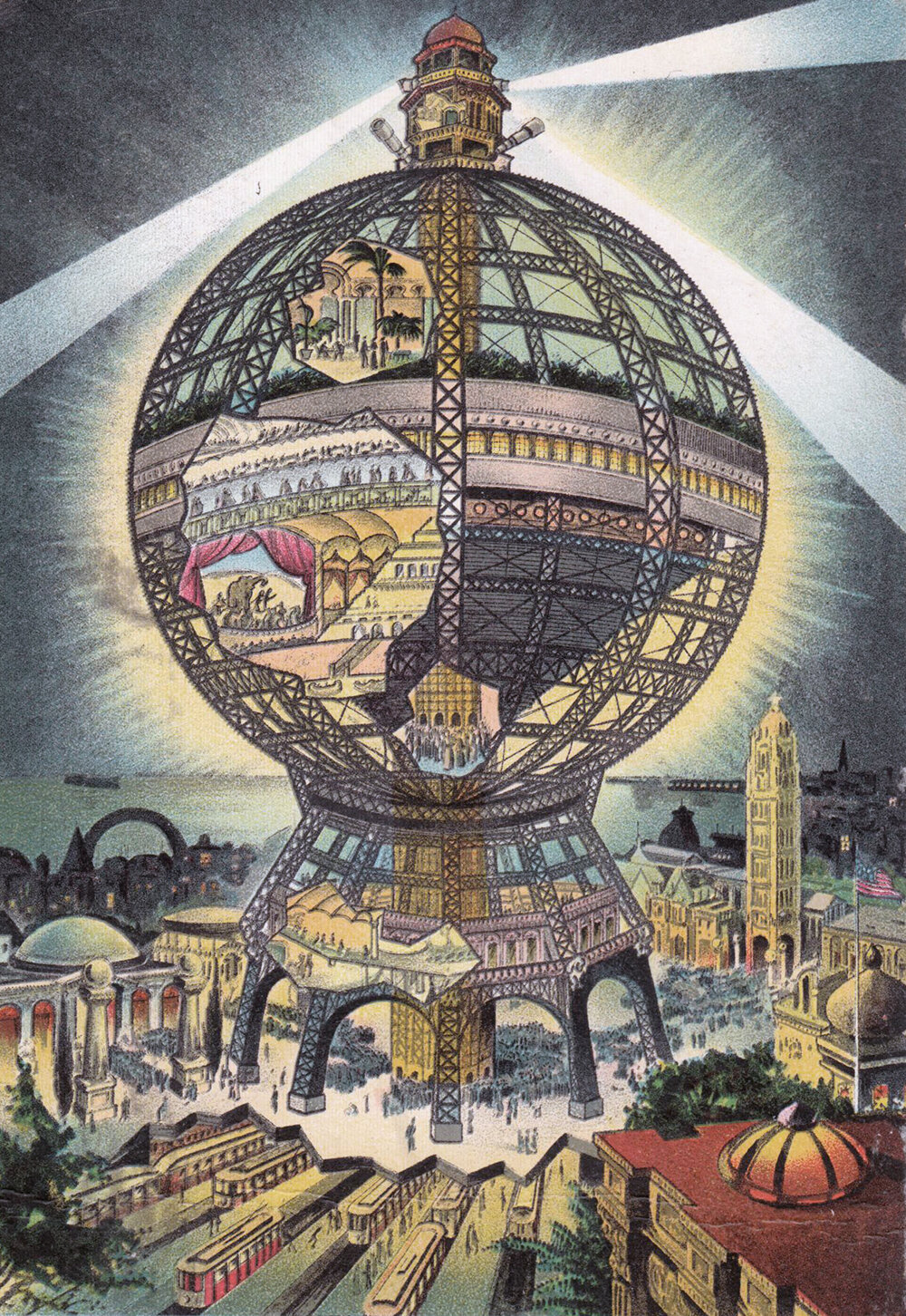

Alberto de Palacio’s Monument to Christopher Columbus

The phenomenal success of the Eiffel Tower has impressed upon the projectors of coming exhibitions the idea that they must strive to rival (if not to surpass) that unique structure by some colossal monumental work. This is the first sentence of an article from 1891 announcing the proposal pictured above. It was a monument to Christopher Columbus, and it was designed by Spanish engineer Alberto de Palacio, to be built for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog

Climbing to the top of a mountain is the closest a person can get to escaping the earth’s surface without taking flight. It’s a triumph over gravity, and it gives the climber a great sense of accomplishment as well as a command over the surrounding landscape. This painting encapsulates all of this beautifully. It was painted around 1818 by Caspar David Friedrich, and it’s called Wanderer Above the Sea and Fog.

A Design for Converting The Crystal Palace Into A Tower 1000 Feet High

Most people familiar with the history of modern architecture know the Crystal Palace. It was built in Hyde Park, London for the Great Exhibition of 1851, and it was designed by Joseph Paxton. What most people don’t know, however, is another architect took the pieces of the Crystal Palace and re-arranged them into a supertall tower proposal. It wasn’t built, of course, but it’s a fascinating proposal that takes advantage of the temporary nature of the original building.

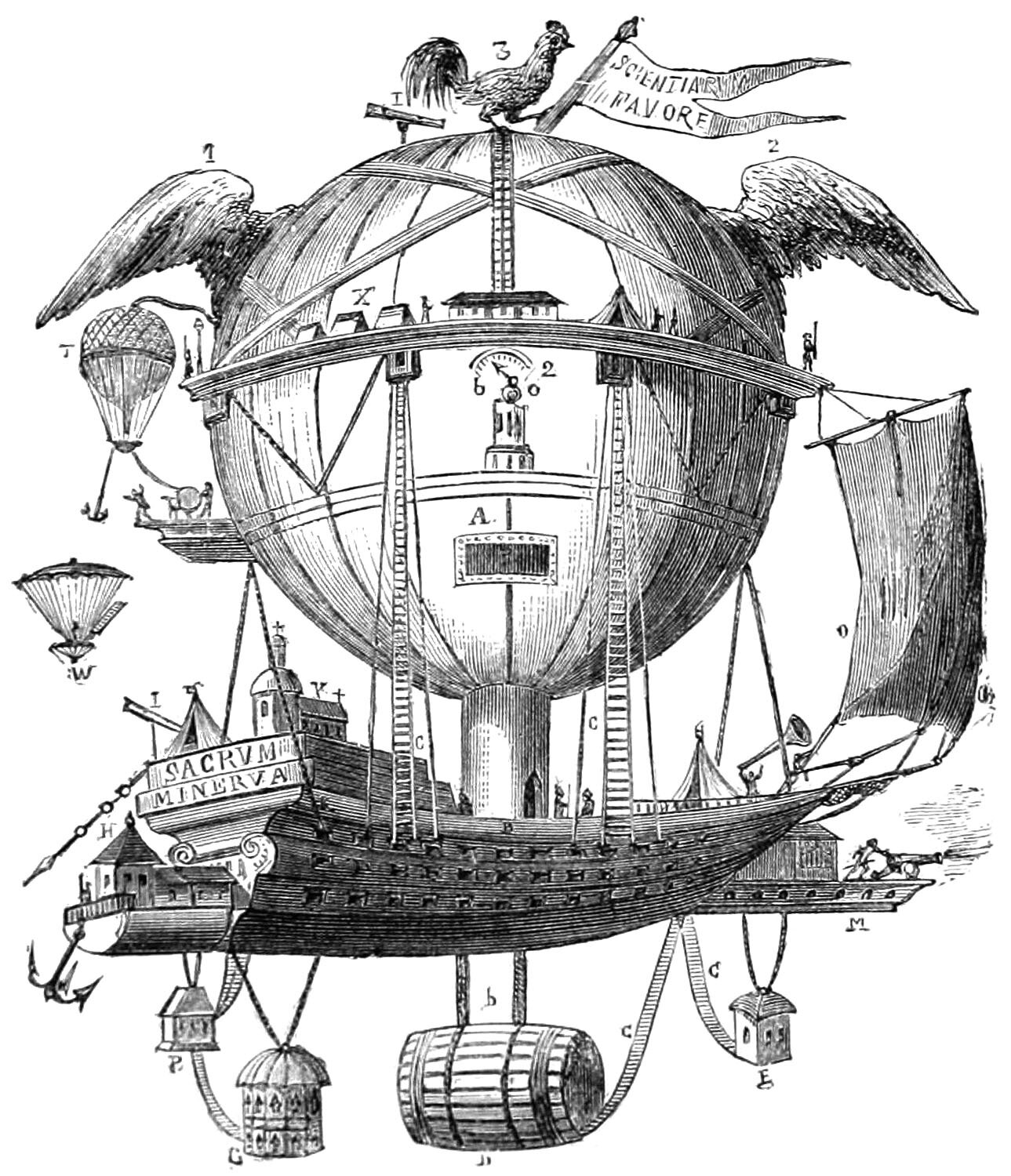

Étienne Gaspard Robert’s La Minerve Airship

Pictured above is an airship design from 1803 by Étienne Gaspard Robert. Robert was a Belgian stage magician and physicist, and he also designed and flew balloons. His most famous design, called La Minerve, is pictured above. It was meant to be an exploratory vessel which would make multi-month trips around the world. Robert described the craft as an aerial vessel destined for discoveries, and proposed to all the Academies of Europe. It’s impractical, naïve, and amazing.

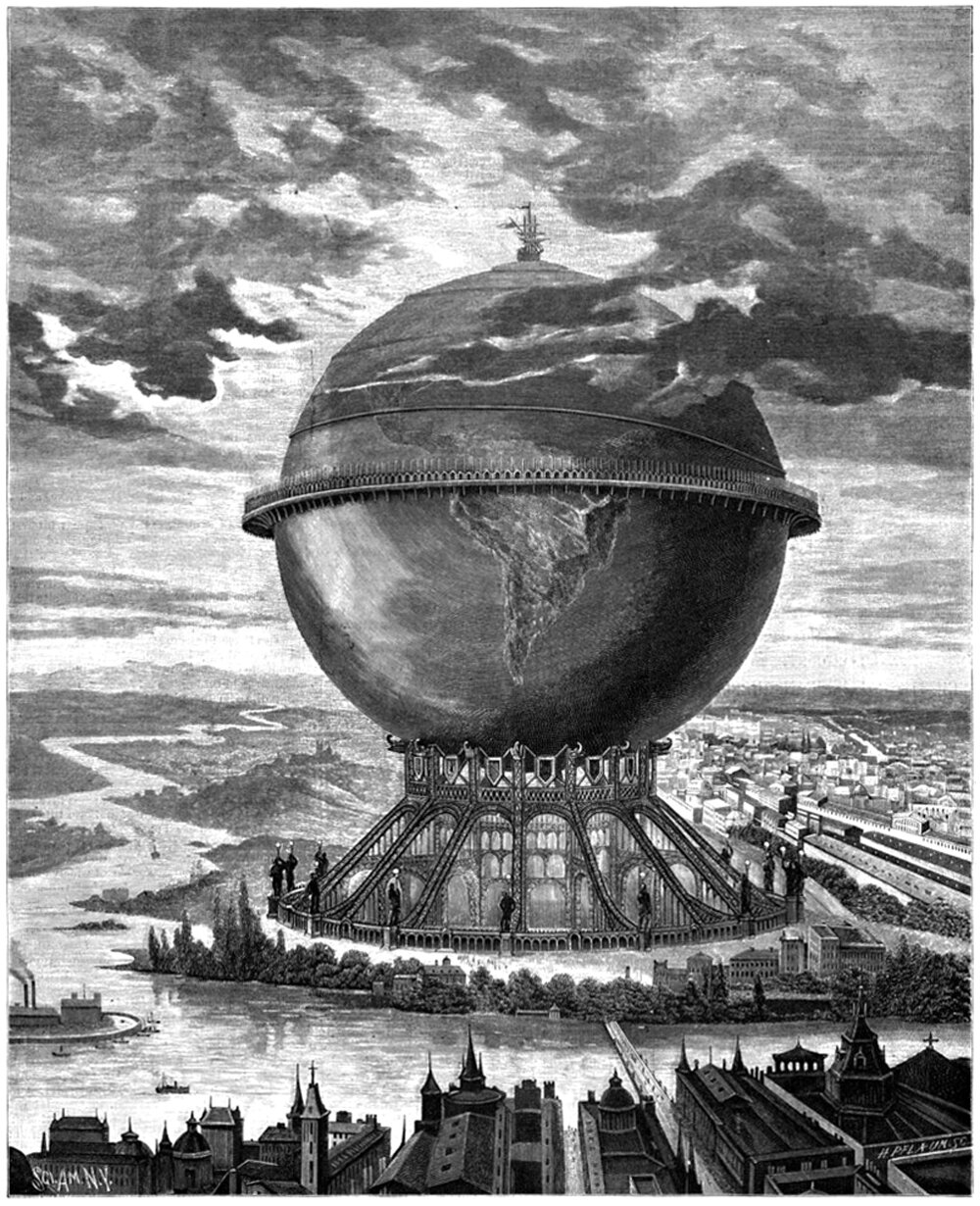

The Coney Island Globe Tower

Pictured above is the Coney Island Globe Tower, proposed in 1906 by Samuel Friede for a lot at the corner of Steeplechase Park in Coney Island, Brooklyn. The building features an enormous globe built of latticed steel, similar in style to the Eiffel Tower. The Globe was designed as an entertainment and leisure complex, and it was marketed as the second tallest building in the world, behind the aforementioned Eiffel Tower. The most intriguing part of the proposal, however, is that it was a fraud.

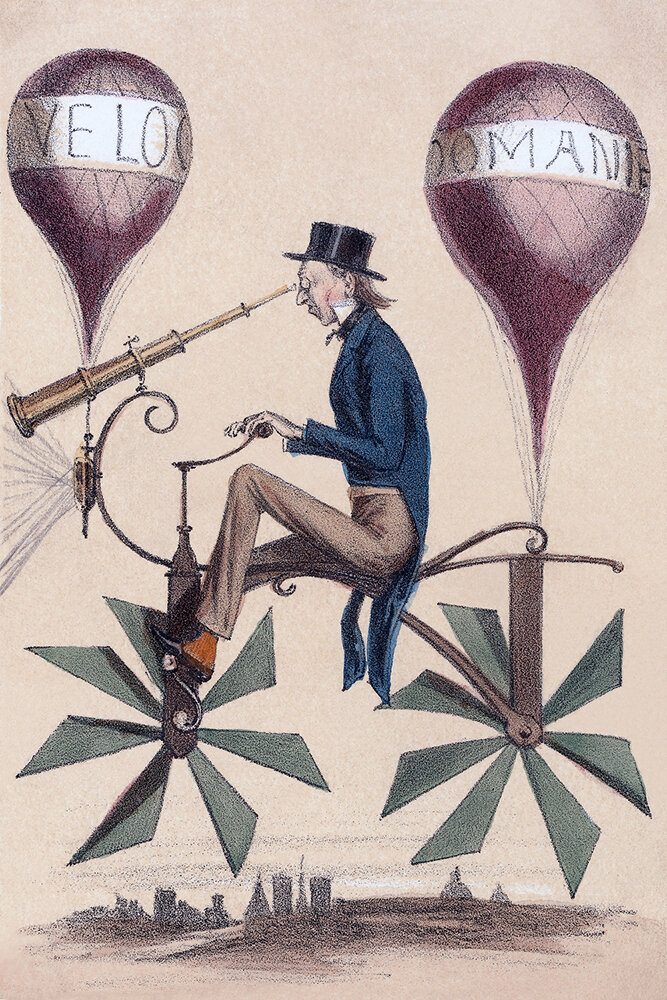

A Voyage to the Moon

There’s a fine line between fiction and invention. Throughout my research into flying machines, I’ve come across many fictional designs that weren’t meant to actually fly, but to evoke the idea of flight. The above cartoon is one of these. It’s a French cartoon from 1867, titled Voyage a la Lune, or Voyage to the Moon. It riffs on the idea of a bicycle that flies, and it’s got a playful feeling about it, as if it doesn’t take itself seriously.