Mountains and Glaciers

Illustration by James D. Forbes of the Nygaard Glacier in Norway, carving its way down a valley between two mountain ridges.

The relationship between mountains and glaciers is a fascinating one. Where glaciers exist, it’s because the morphology of a mountain has created the conditions necessary for a glacier to form. Once this happens, a glacier’s growth and movement will slowly erode away the very mountain that created it. Over time, this movement carves the landscape into valleys, cirques, arêtes, cols, moraines, fjords, and various other landforms.

If a mountain is tall enough, it will impede air movement and affect the weather surrounding it. If it’s cold enough at the top, this results in freezing temperatures and snowfall. For a glacier to form, two main conditions must be met at a specific place on the mountain. First, the snow must accumulate at a faster rate than it melts off. Second, this must initially occur at a low-sloped or self-contained area; otherwise the snow would just fall down the mountain and not accumulate over time. If these two conditions are met, a mass of snow will build up over time. As more and more snow falls over the years, the increasing weight will cause the snow at the bottom to compact until it eventually turns to glacial ice. This mass of ice and snow is called a glacier. As the glacier grows over time, it will increase in volume until it overflows the spot it started growing in. This overflow will progress down a mountainside, much like a slow-moving river. As the glacier flows, the immense force and weight will carve up and flatten the landscape, resulting in the landforms mentioned above.

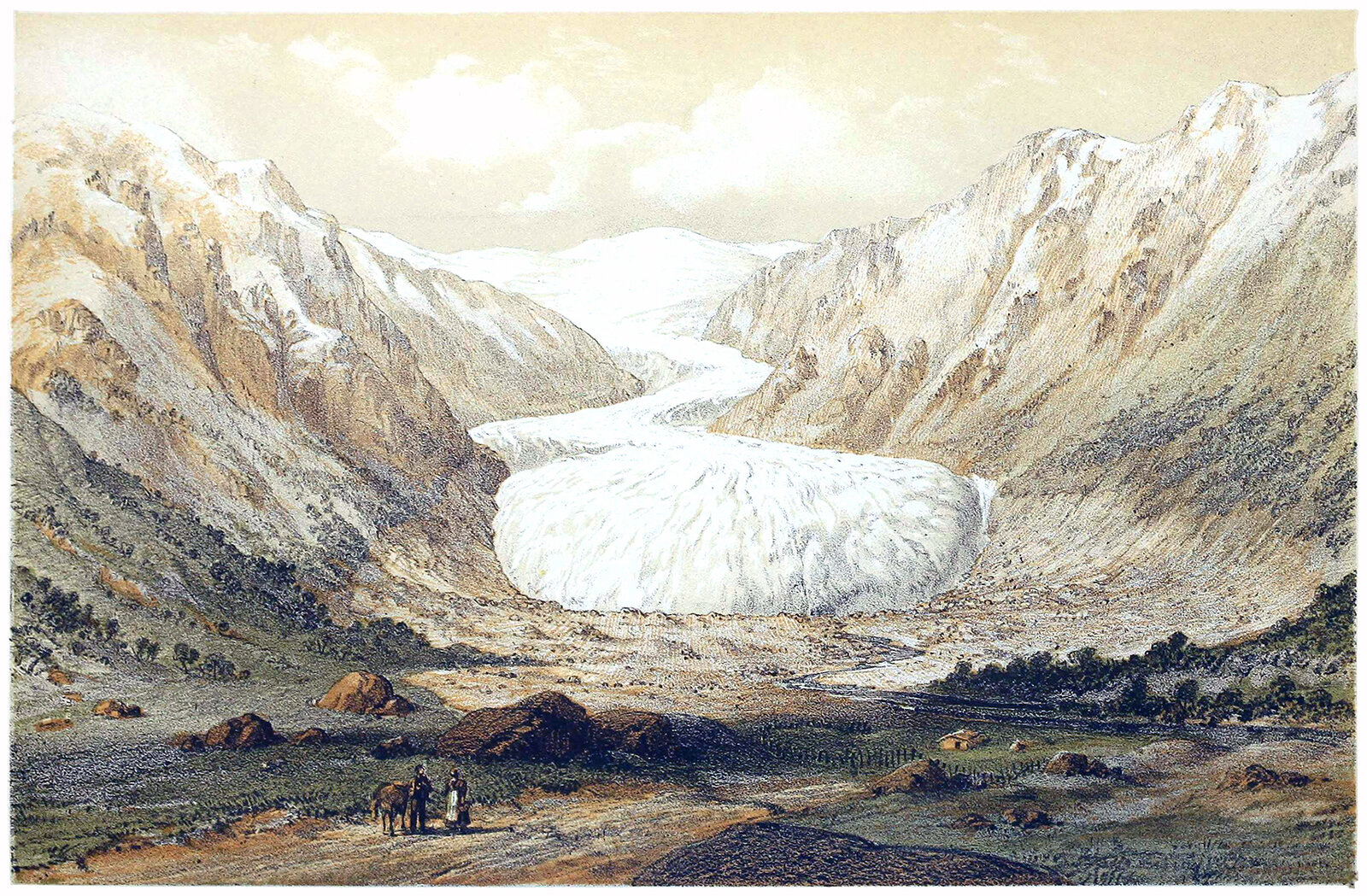

Illustration by James D. Forbes of the Suphelle Glacier in Norway, emerging between two mountains and spilling out on a valley floor.

The illustrations chosen for this piece each show a glacier in different circumstances. Pictured at the top is a view of an alpine glacier flowing down a mountain valley. This view does a great job of making a glacier look like a frozen river, guided both by gravity and flowing along the path of least resistance. On either side of the mass is a mountain range, which is slowly being eroded away by the passing ice flow. Pictured above is another alpine glacier that’s flowing down a mountainside. There’s a large mass of snow and ice at the top left of the image, and the excess mass is flowing down the slope into a valley below. This type of alpine glacier is carving a valley into the mountain itself. Over time this flow will eat away at the slope until a valley is formed on the side of the mountain. Pictured below is another glacier flowing down a mountainside, but this one has carved a valley for itself. You can also see a creek to the right that is carving out an adjacent valley. Both of these water sources appear to be draining into the river shown at the bottom right.

Illustration by James D. Forbes of the Bondhuus Glacier in Norway, flowing down a high mountain pass and down into a valley.

Glaciers exist on a time-scale that is much larger than ours. At first glance, they don’t appear to move or flow, but over time they are wonderfully dynamic. This is most evident at a glacier’s foot, or terminus. Here, the glacier melts faster than it accumulates, and throughout the year it will swell and recede in a cycle. As winter weather causes more snow to accumulate, the foot of a glacier pushes forward as its mass swells. As summer weather melts away at the snow and ice, the foot will recede, or shrink. The amount of swelling and shrinking can very widely; typical flow rates for glaciers range from 1 meter (3 ft) per day, up to 20-30 meters (70-100 ft) per day. This cycle is visible in the first image; the lighter area in front of the glacier’s foot has been cleared by the glacier in the past, and its current state has receded back from this point.

The relationship between mountains and glaciers is rooted in verticality. The height of a mountain creates the conditions necessary for a glacier to form, and once formed the glacier works with gravity to erode away at the mountain while flowing towards lower ground. It’s a sublime example of how verticality shapes the natural world.

Check out other posts about mountains here.