Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mile High Skyscraper Proposal

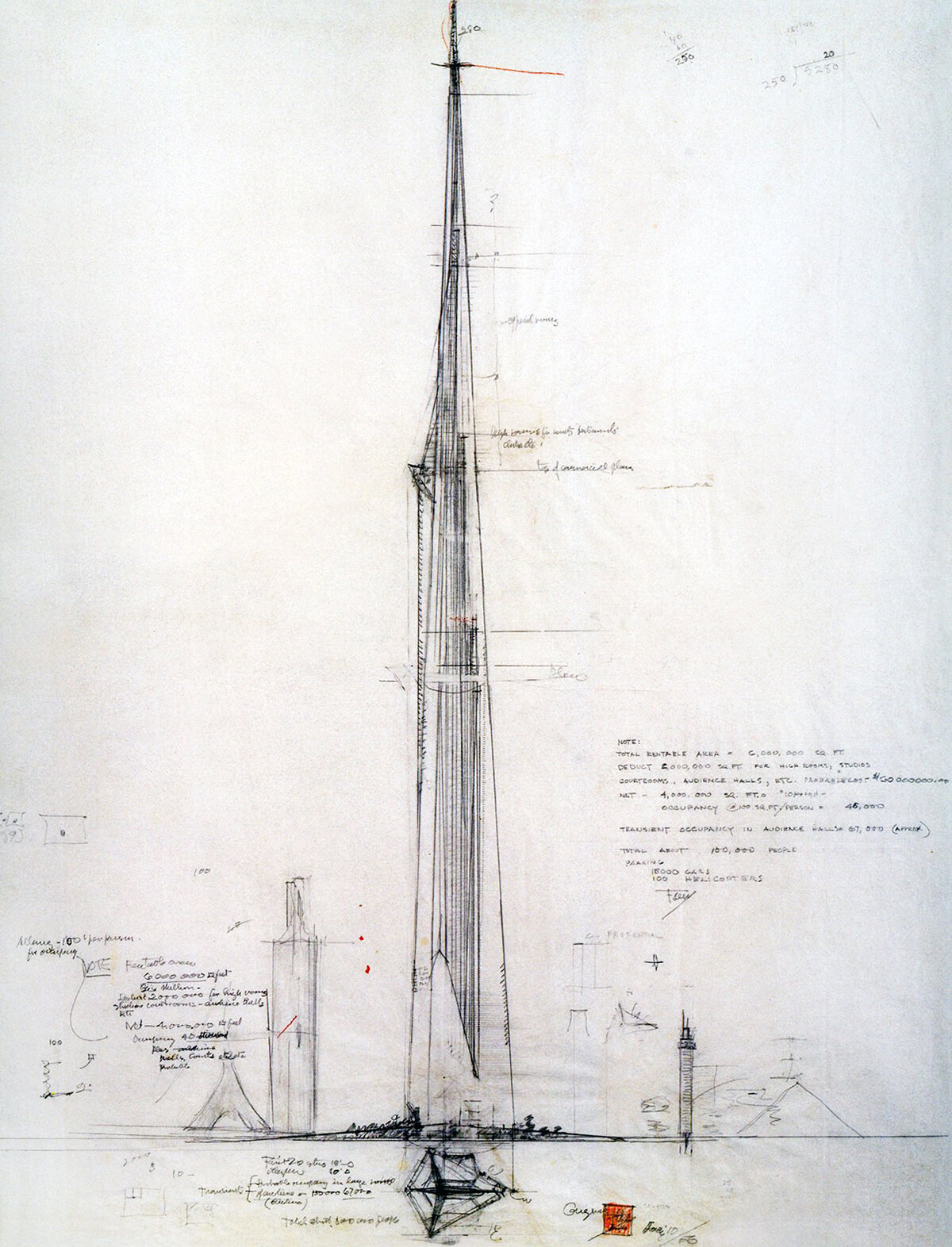

Main perspective rendering and project description for Frank Lloyd Wright’s Illinois skyscraper proposal.

In the debate over density, architects and planners are split into two camps. The first is pro-density, which believes in dense, centralized cities that function through complex mass-transit systems and clusters of skyscrapers. This is the pro-city crowd. The second is the anti-density camp, which believes in de-centralized, spread-out networks of neighborhoods that rely on automobiles and low buildings. This is the pro-suburb crowd. Modern architect Frank Lloyd Wright was an outspoken member of the latter camp, and his visionary Broadacre City project is a model suburb, with low buildings and green space prioritized over tall buildings and density.

In addition to his anti-city stance, Wright is famous for his organic approach to architecture, which is based on a building’s intimate connection to its surroundings. Organic buildings respond to their context and should be unique to their site. The antithesis of this is a design that can be built anywhere and is out-of-context. This includes skyscrapers and tall buildings in general. With this in mind, it’s hard to believe the tower design pictured above came from Wright. It’s called The Illinois, and it was planned to be a mile (1,609 meters, or 5,280 feet) in height. That’s more than four times the height of the Empire State Building, and nearly twice the height of the Burj Dubai.

Concept sketch of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Illinois skyscraper proposal. Wright shows the main silhouette of the tower, along with height comparisons of other famous tall buildings throughout history.

Wright’s justification for the project was quite clever. He argued that the sheer size of The Illinois would encapsulate an entire city within a single building, which would kill two birds with one stone. It would provide the density that people crave, while freeing up the surrounding landscape for his Broadacre City plan, with its parks and low buildings. Essentially, Wright was using the if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em mentality when it came to the city. Give ‘em their density so they can come together, but concentrate it into one massive structure and surround it with your larger vision for the world-as-one-big-suburb. He envisioned skyscrapers like this built here and there throughout the countryside, taking the place of cities. That way, everyone could live in a suburban paradise, surrounded by green space and ample daylight.

Floor plan illustration of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Illinois skyscraper.

The tower itself had a tripod-like design, with three wings of structure and a central core. This tripod, combined with a tapered form that came to a point at the tower’s summit, were used by Wright to shed wind forces. At the base, Wright used his taproot foundation design that took inspiration from a tree. He had previously used it for another of his tower designs, the S.C. Johnson Research Tower. The foundation, much like the tower, burrows into the earth and progresses down to a point at its base.

Section illustration showing the base of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Illinois skyscraper. Pictured is Wright’s taproot foundation, which is inspired by tree structures.

It’s telling that an architect as outwardly anti-density as Wright would put in a design for the world’s tallest building. It’s also telling that he went a step further and designed a mile-high building, which is far and away taller than any other building ever built. This suggests two theories about his motivations. First, he exaggerated the height of The Illinois so much because he was trying to point out the absurdity of the tall building race and skyscrapers in general. This wink-wink approach seems a bit far-fetched, but still believable considering Wright’s massive ego. Second, and much more believable, is that Wright was silently acknowledging the need for humanity to achieve verticality, even if it ran contrary to his beliefs about the city. After all, he was no stranger to the building type; his previous tower designs include the S.C. Johnson Research Tower, Saint Mark’s Tower, and Price Tower. In addition, he’s quoted as saying that towers have always been erected by humankind - it seems to gratify humanity’s ambition somehow and they are beautiful and picturesque.[1] This is Wright acknowledging the human need for verticality, and his design for The Illinois is evidence that even those of us who are anti-density still have this need within themselves.

Check out other unbuilt designs here.

[1]: Wright was speaking to the Taliesin Fellowship on 19 August, 1956 when he said this. It was three years before he died.