Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

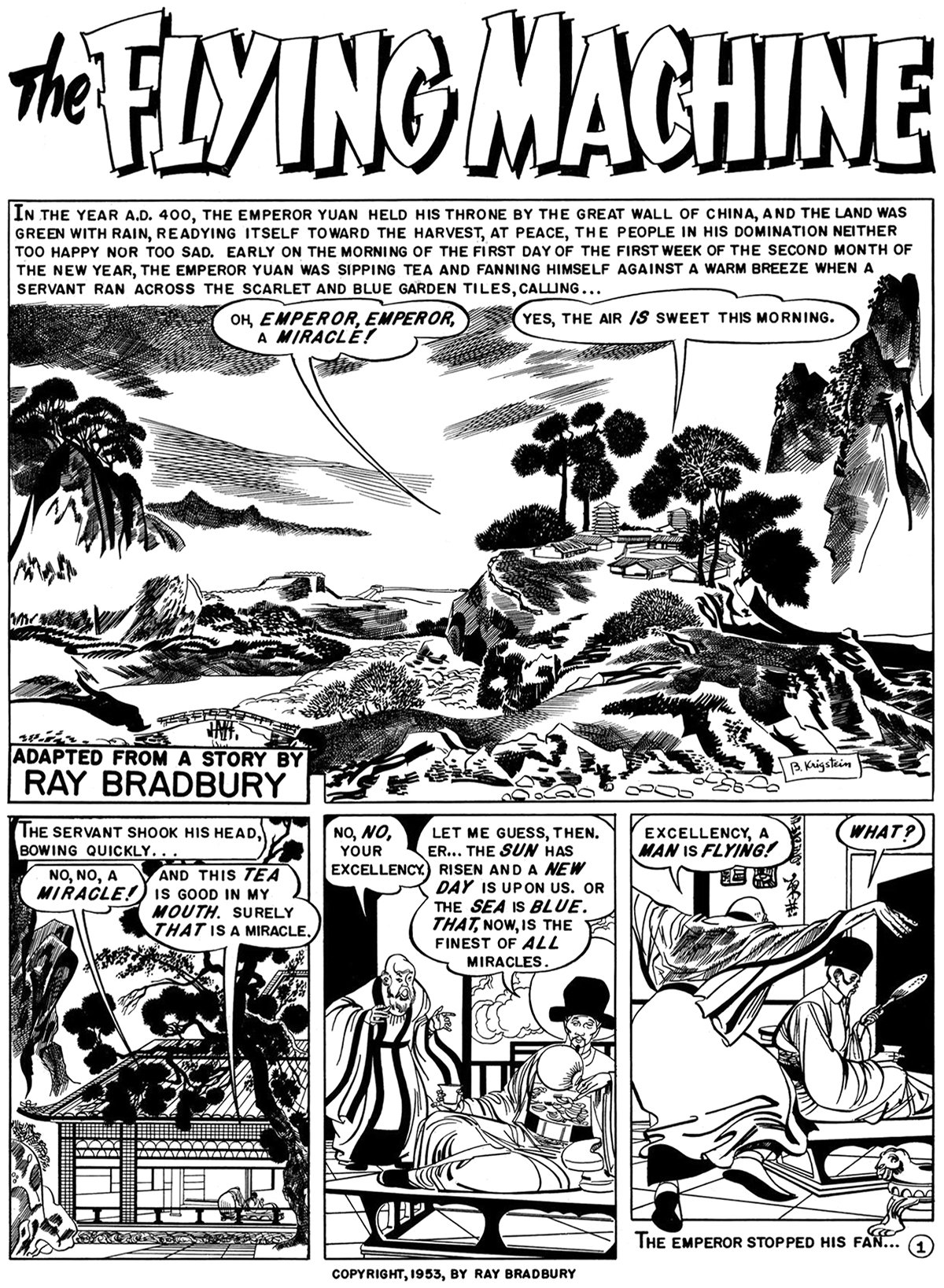

The Flying Machine by Ray Bradbury

With great power comes great responsibility. This is the major theme of Ray Bradbury’s short story from 1953, titled The Flying Machine. It was adapted into a comic in 1954 by Al Feldstein, and the full piece is pictured here. It tells the story of a meeting between an emperor and an inventor who has built a flying machine. The inventor is an optimist who experiences the full delights of flying, while the emperor is a pessimist who fears the technology will fall into the wrong hands. It’s a theme that runs much deeper than human flight, but Bradbury’s choice to feature the flying machine demonstrates the power of flight for humanity.

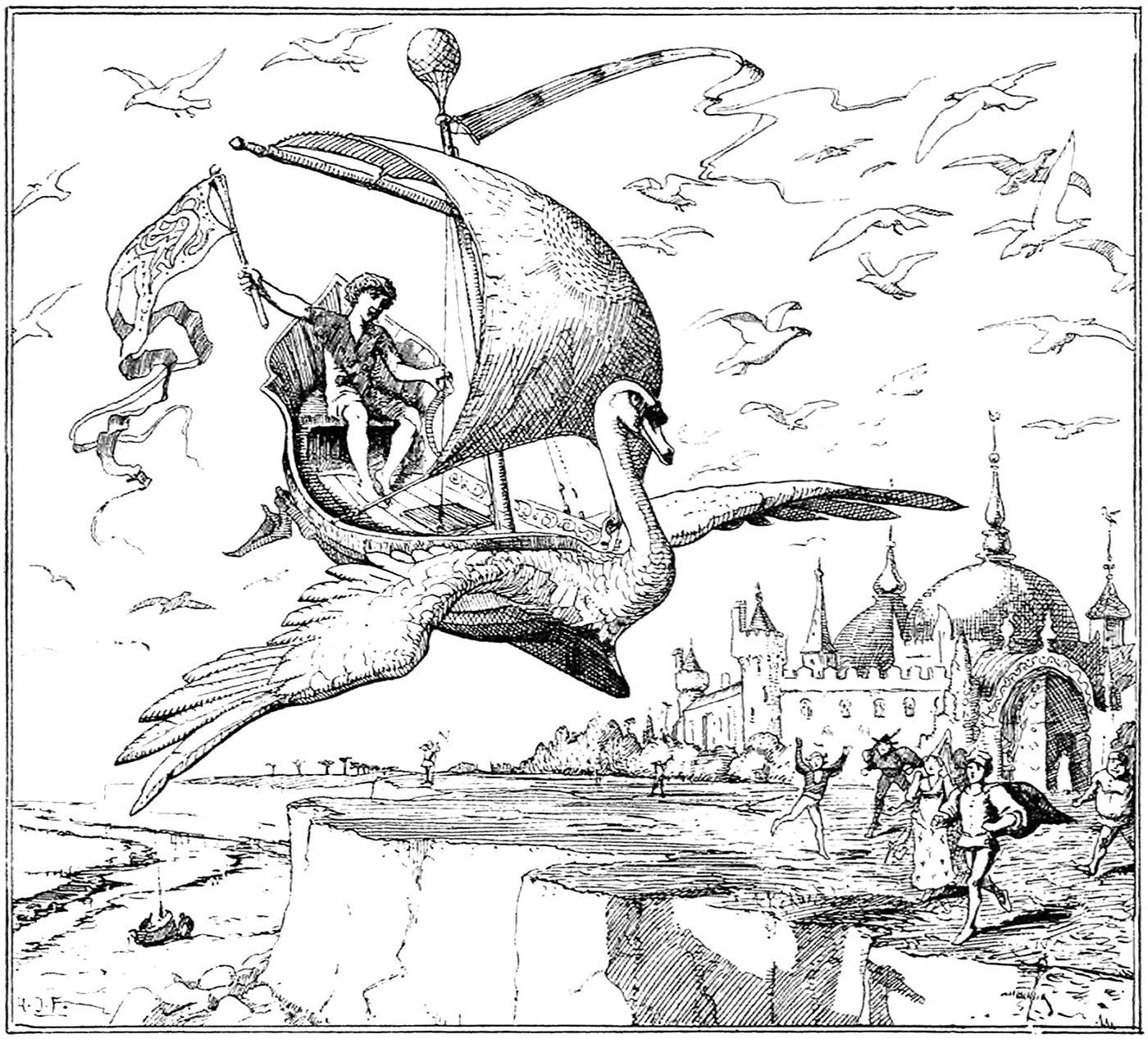

Minnikin’s Flying Ship

‘Now go over fresh water and salt water, over hill and dale, and do not stop until thou comest to where the King’s daughter is,’ said Minnikin to the ship, and off it went in a moment over land and water till the wind whistled and moaned all round about it.

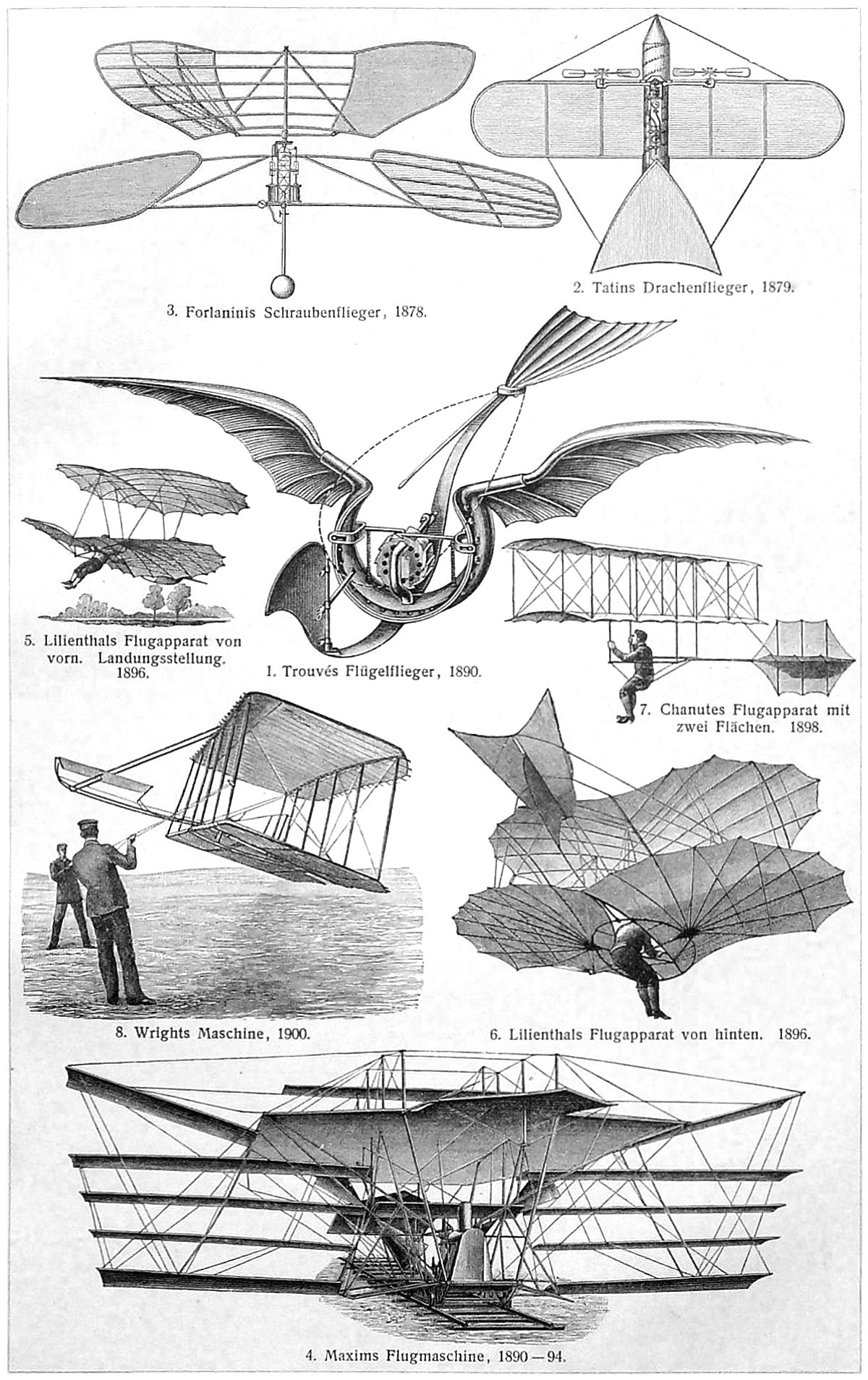

Early Aeronautics

Pictured above is a collage of early flying machines, originally published in the German encyclopedia Meyers Konversations Lexikon. I love collages like this because the illustrator inevitably must pick and choose which examples to show. This is most likely done for a combination of reasons, including available illustrations, the most famous examples, and page layout.

E.P. Frost’s Ornithopters

Pictured above is a photo of E.P. Frost’s second ornithopter prototype. It consisted of a large a pair of wings and a metal scaffold, and it was powered by an internal combustion engine. According to Frost, the machine successfully achieved liftoff under its own power in 1904. This wasn’t a sustained flight, however, but rather a jump or a hop.

There's no sensation to compare with this. Suspended animation, a state of bliss. Can't keep my mind from the circling sky. Tongue-tied and twisted, just an earth-bound misfit, I.

-David Gilmour of Pink Floyd, English songwriter and musician, born 1946.

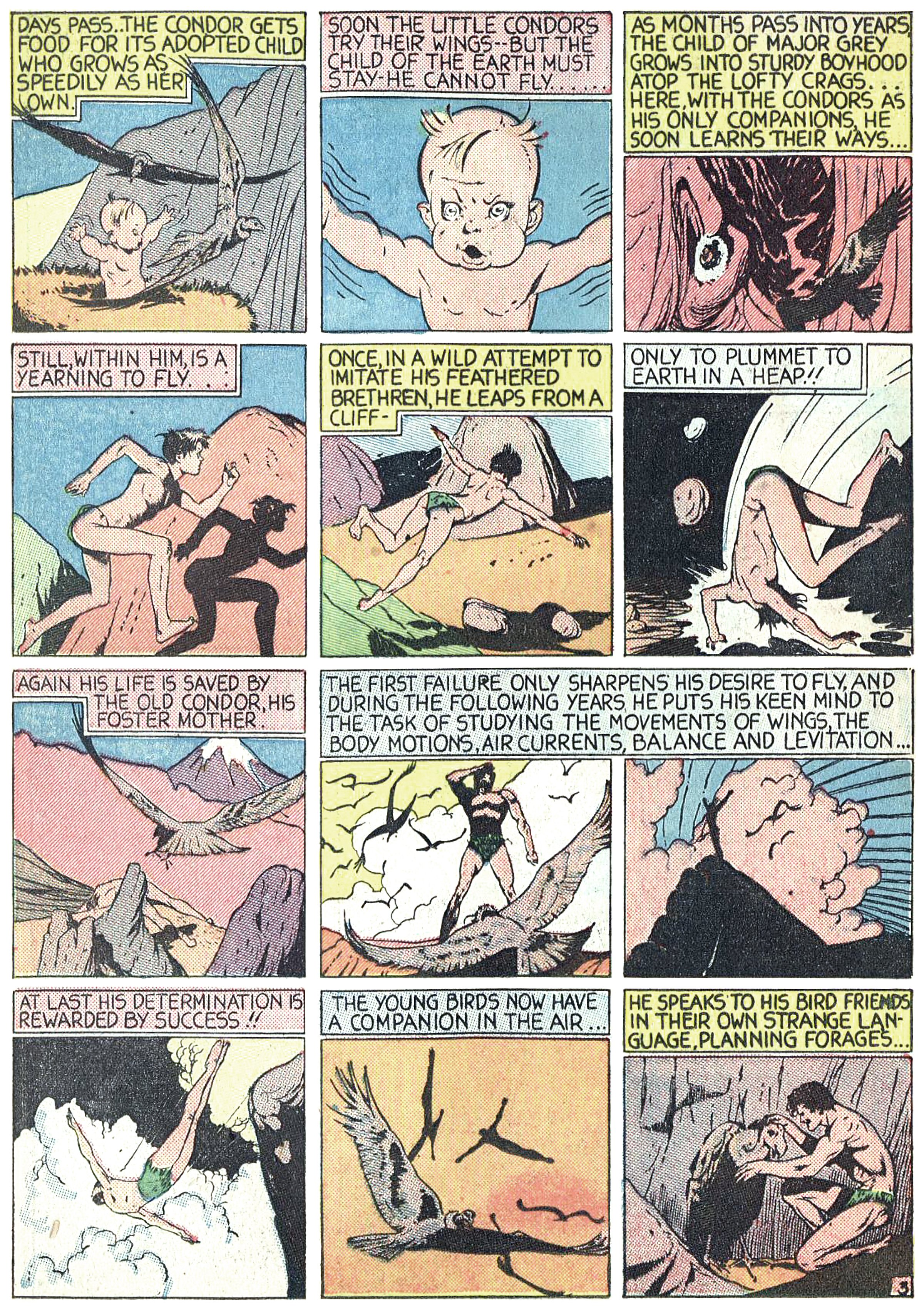

The Black Condor : The Man Who Can Fly Like A Bird

The first failure only sharpens his desire to fly, and during the following years, he puts his keen mind to the task of studying the movements of wings, the body motions, air currents, balance and levitation.

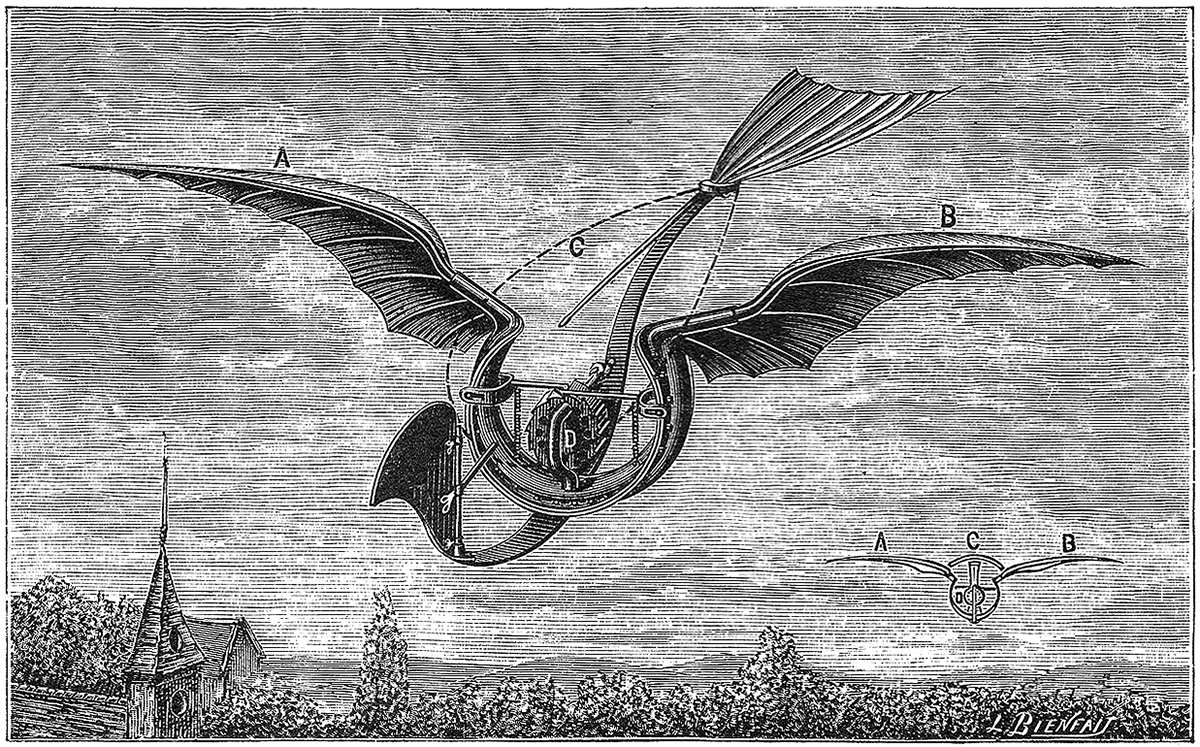

Gustave Trouvé’s Flügelflieger

Pictured above is an ornithopter design from 1891 by French polymath and inventor Gustave Trouvé. It was called the Flügelflieger, which means winged flyer in German. It featured a pair of wings, a tail, a front rudder, and it was powered by a centrally-placed rapid-succession gun cartridge. Due to the gunpowder charges, the machine was quite loud when flapping. It did work though; according to Trouvé it made a successful flight of 80 meters (262 feet) on 24 August 1891.

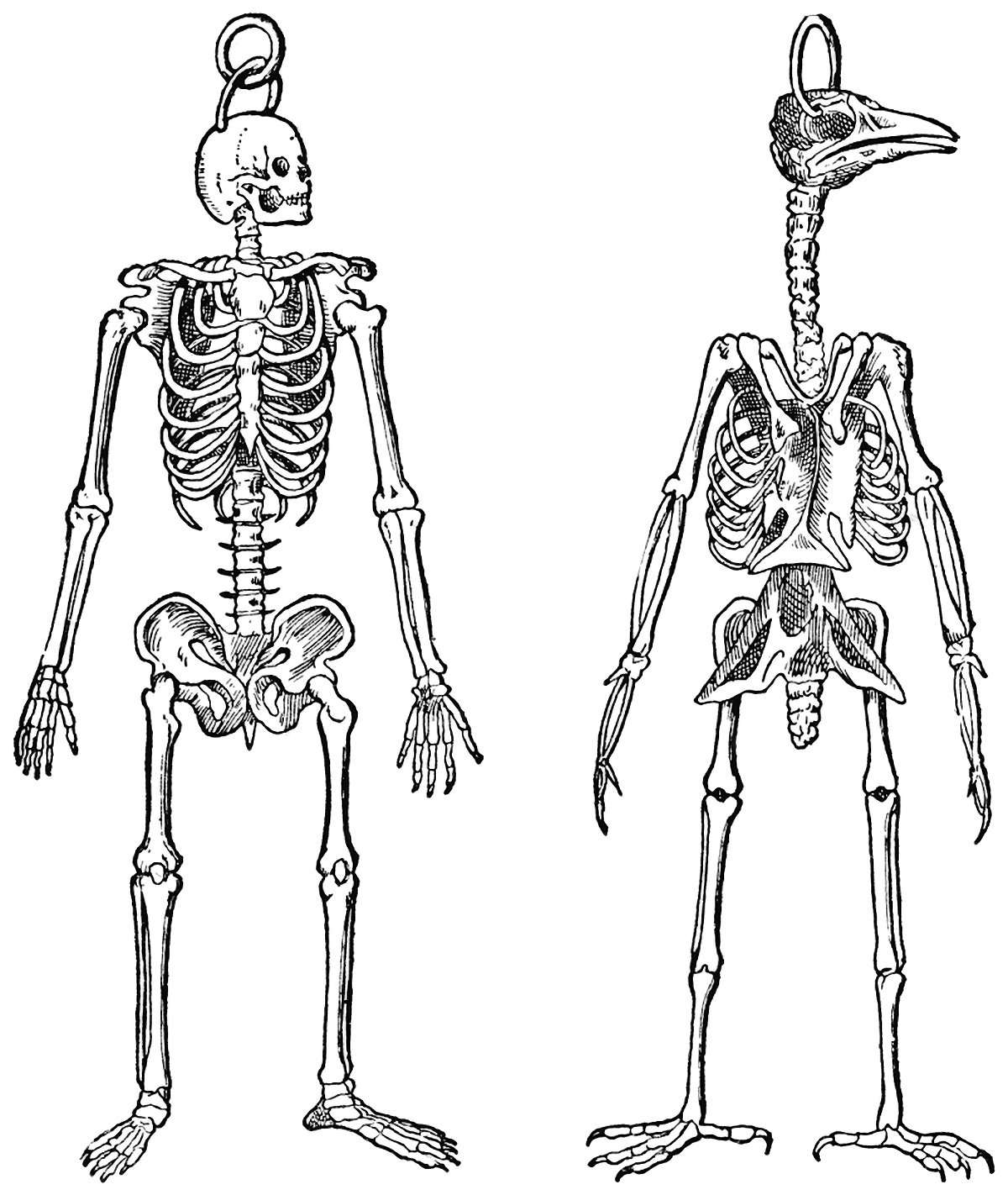

The Skeletons of a Man and Bird

Pictured above is a comparison between the skeleton of a human and a bird. What I find fascinating about this image is the choice of the artist to position the bird in a bipedal stance. I suspect this was done just to ease the comparison, but in a way it undermines the birds power of flight. This is an animal who is at home when in the open air, but here the bird is shown with its feet firmly planted on the ground, much like a human. The playing field has been leveled, so to speak, which puts the bird at a specific disadvantage.

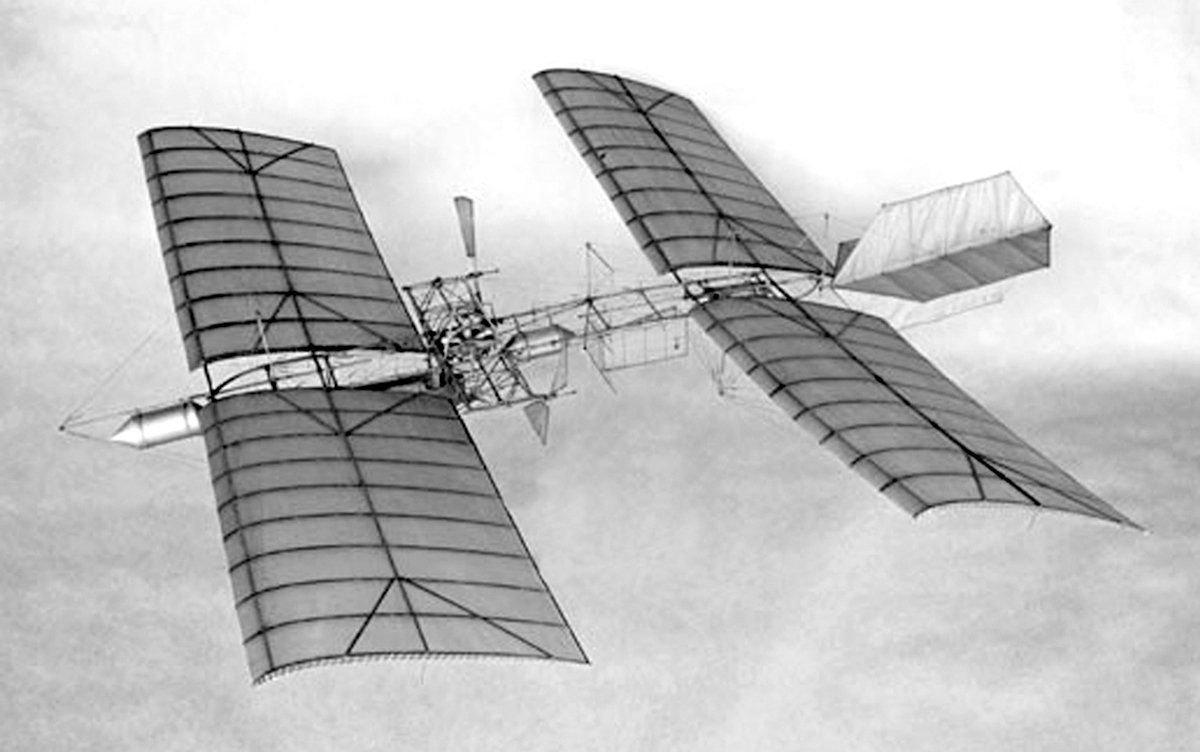

Samuel Langley’s Aerodrome

Samuel Langley was an astronomer and physicist who was the third secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was also a pioneer of aviation, most famous for his designs of the Langley Aerodrome, which he built and tested from 1901 to 1903. Pictured above is a photo of his Aerodrome No. 5, which was a pilot-less model that had success flying. Langley was unable to repeat this success with larger, piloted designs, however.

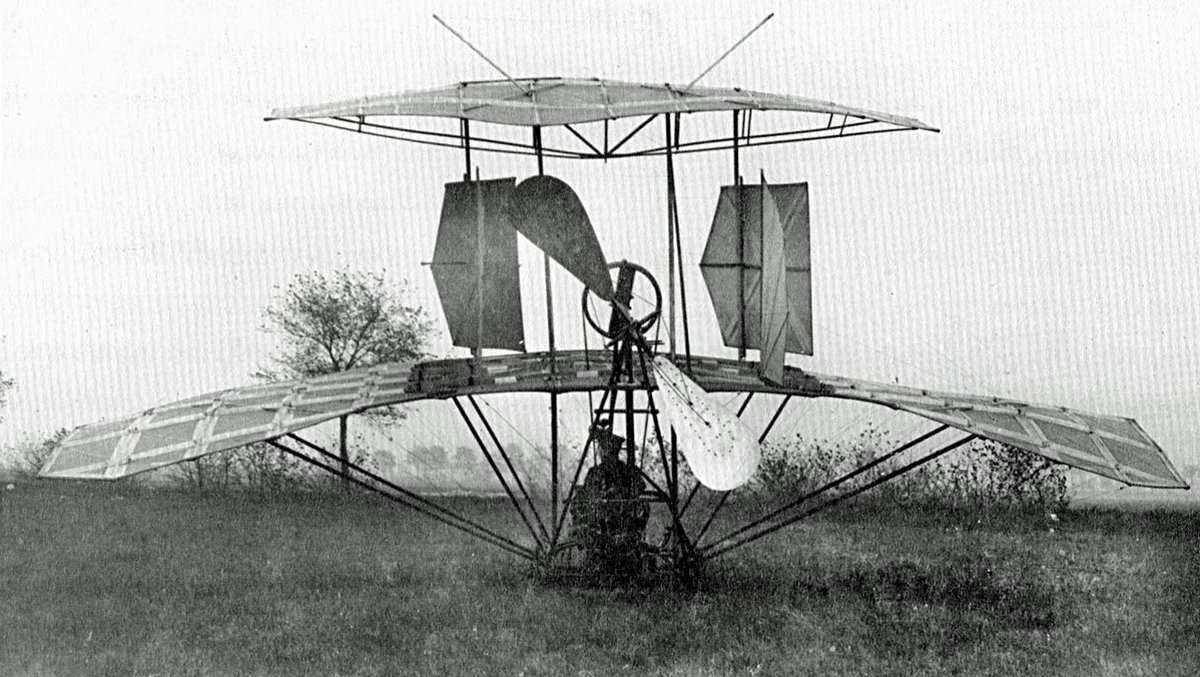

The Jatho Biplane and a Challenge to the Wright Brothers

Pictured above is the Jatho Biplane, built in 1903 by the German aviation pioneer Karl Jatho. During 1903, Jatho made a series of low flights with his machine outside Hanover, Germany. These flights took place a few months before the Wright Brothers achieved powered, controlled flight. We don’t know for sure if the Jatho Biplane was controlled, however. If it was, that means the Wright Brothers weren’t the first to achieve flight. If it wasn’t, the Jatho Biplane is just another prototype that got close, but didn’t actually achieve flight.

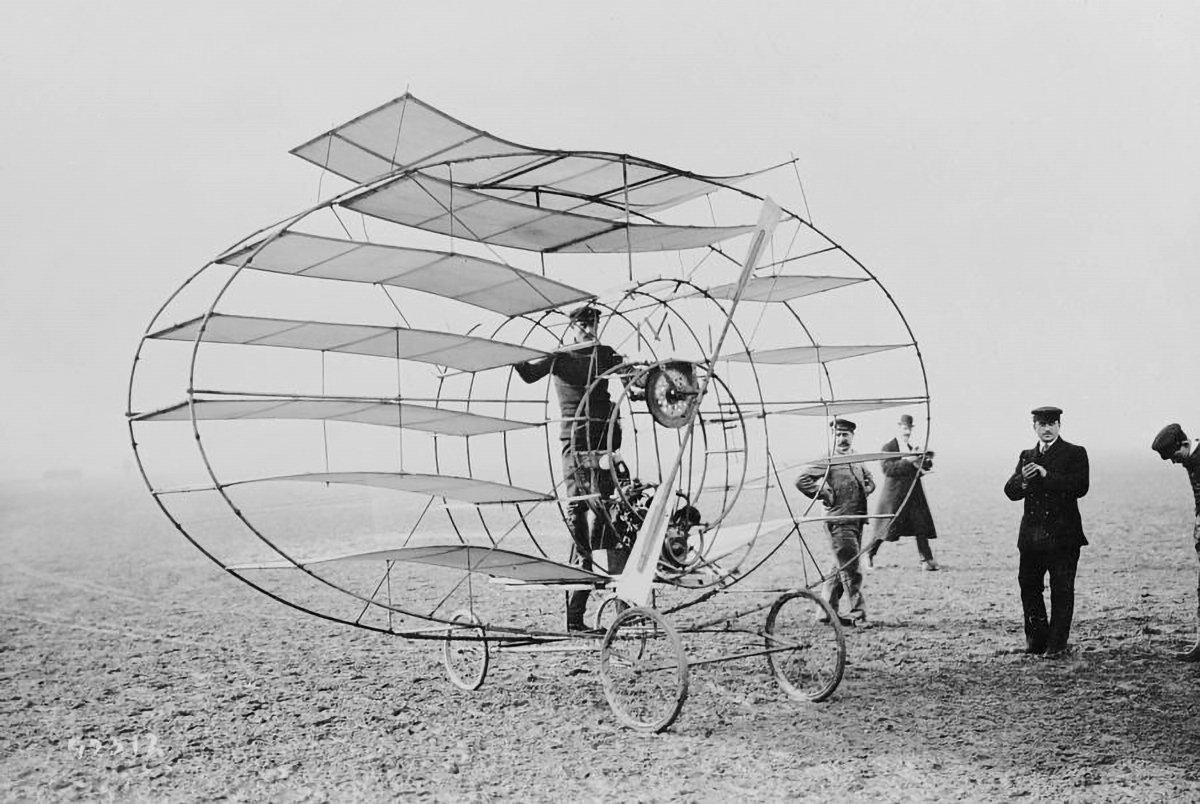

The Marquis Multiplane

If two wings can provide enough lift to make an aircraft fly, surely adding more wings must make it fly even better, no? It’s a silly question by today’s standards, but in the early days of flight it was a legitimate inquiry to be studied. One man who decided to test the theory was Marquis d'Ecquevilly, and pictured above is the Marquis Multiplane which he designed in 1908.

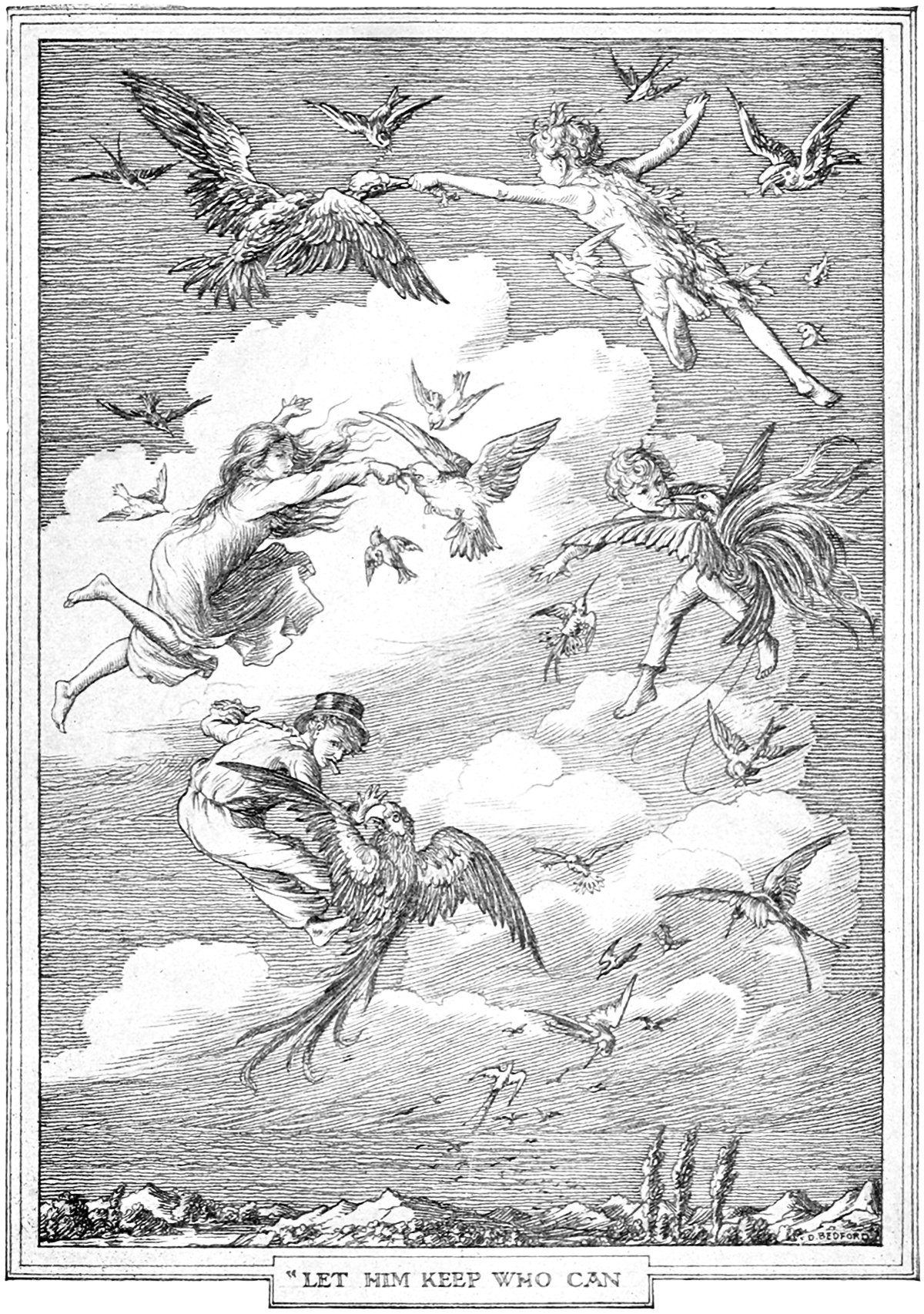

Peter Pan and the Delights of Flying

Peter Pan is perhaps best known from the animated 1953 film Peter Pan, but his story originated in the book Peter and Wendy, written in 1911 by J. M. Barrie. It’s a story of fairies, mermaids, pirates, and a mischievous boy with the power of flight. This boy, named Peter Pan, has adventures in Neverland with a group of British children that he teaches to fly. Flight is central to the narrative of the story, and Barrie does a good job of describing the children’s joy as they learn to fly.

“The honor of inventing the airplane cannot be assigned wholly to one man; like most other inventions, it is the product of many minds.”

-Richard Pearse, Kiwi inventor and aviator, 1877-1953.

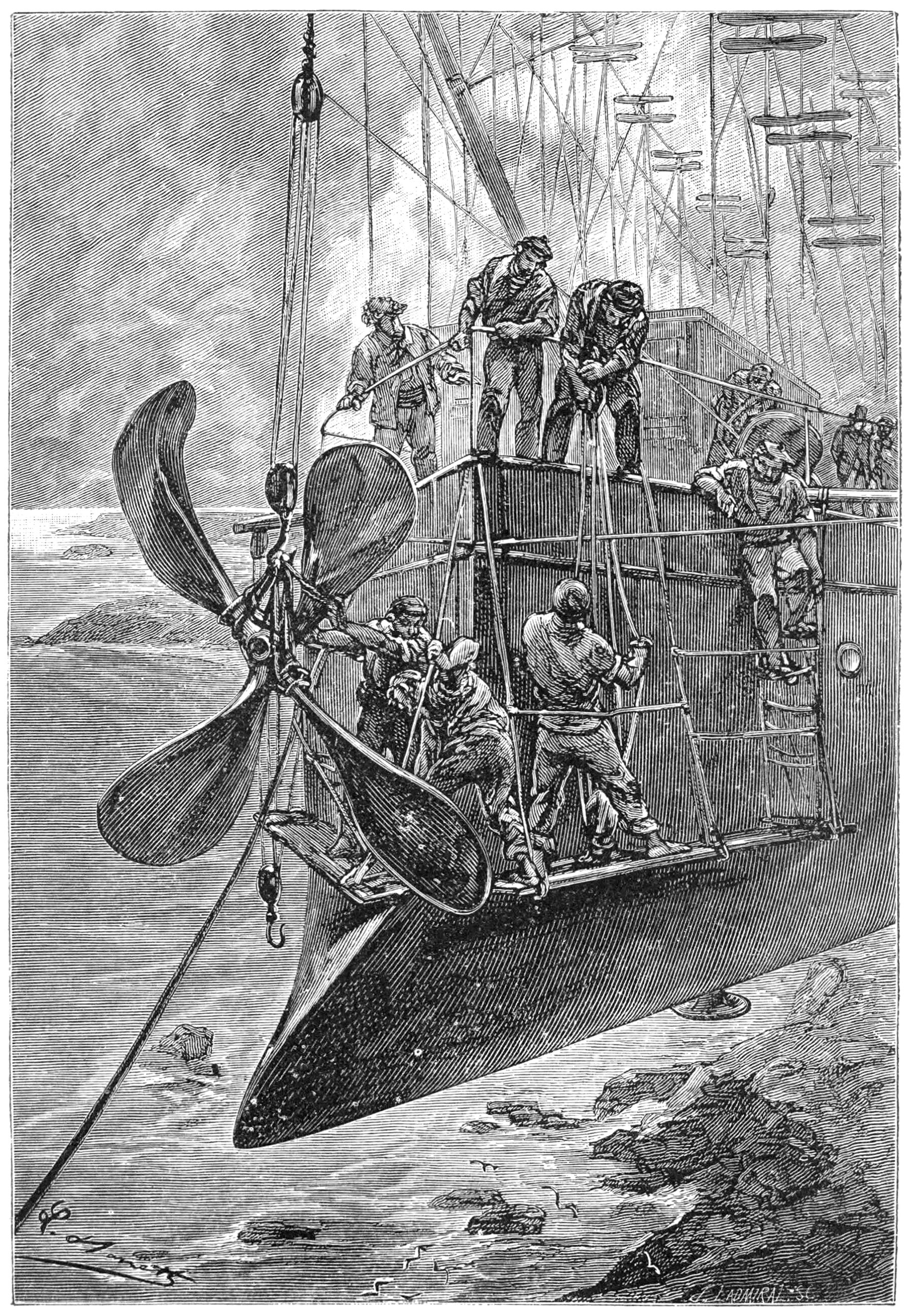

Jules Verne’s Clipper of the Clouds

Fiction has a way of reflecting and informing reality. Pictured above is an illustration from Jules Verne’s novel Robur the Conqueror, published in 1886. It shows a fictional flying machine called the Clipper of the Clouds, which was built by the novel’s titular character. Throughout the story, Verne explores the nature of flight, its effects on humanity, and the general sense of public awe in the early days of flying machines. There’s also an undertone of the God versus Ego struggle that is central to the verticality narrative.

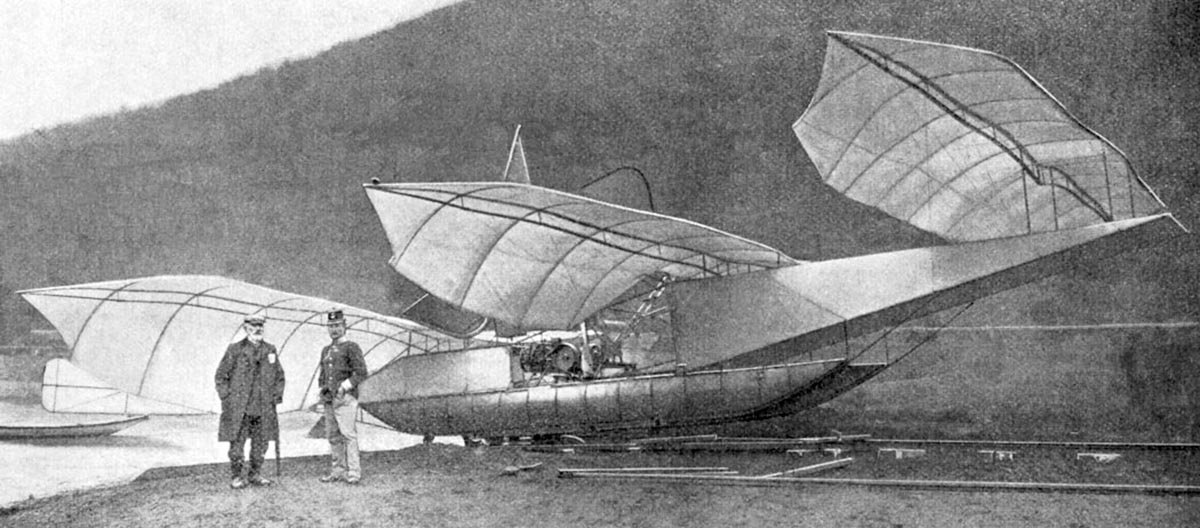

Wilhelm Kress’ Drachenflieger

Pictured above is the Drachenflieger, which was an experimental aircraft designed in 1901 by Austrian engineer Wilhelm Kress. It’s name means Dragon Flyer in German, and it was an attempt by Kress to build the world’s first heavier-than-air flying machine. The craft consisted of a central undercarriage and three large pairs of wings, each set at a different height so they wouldn’t interfere with one another. It was meant to take off and land on the water, so Kress designed it to rest on two pontoons.

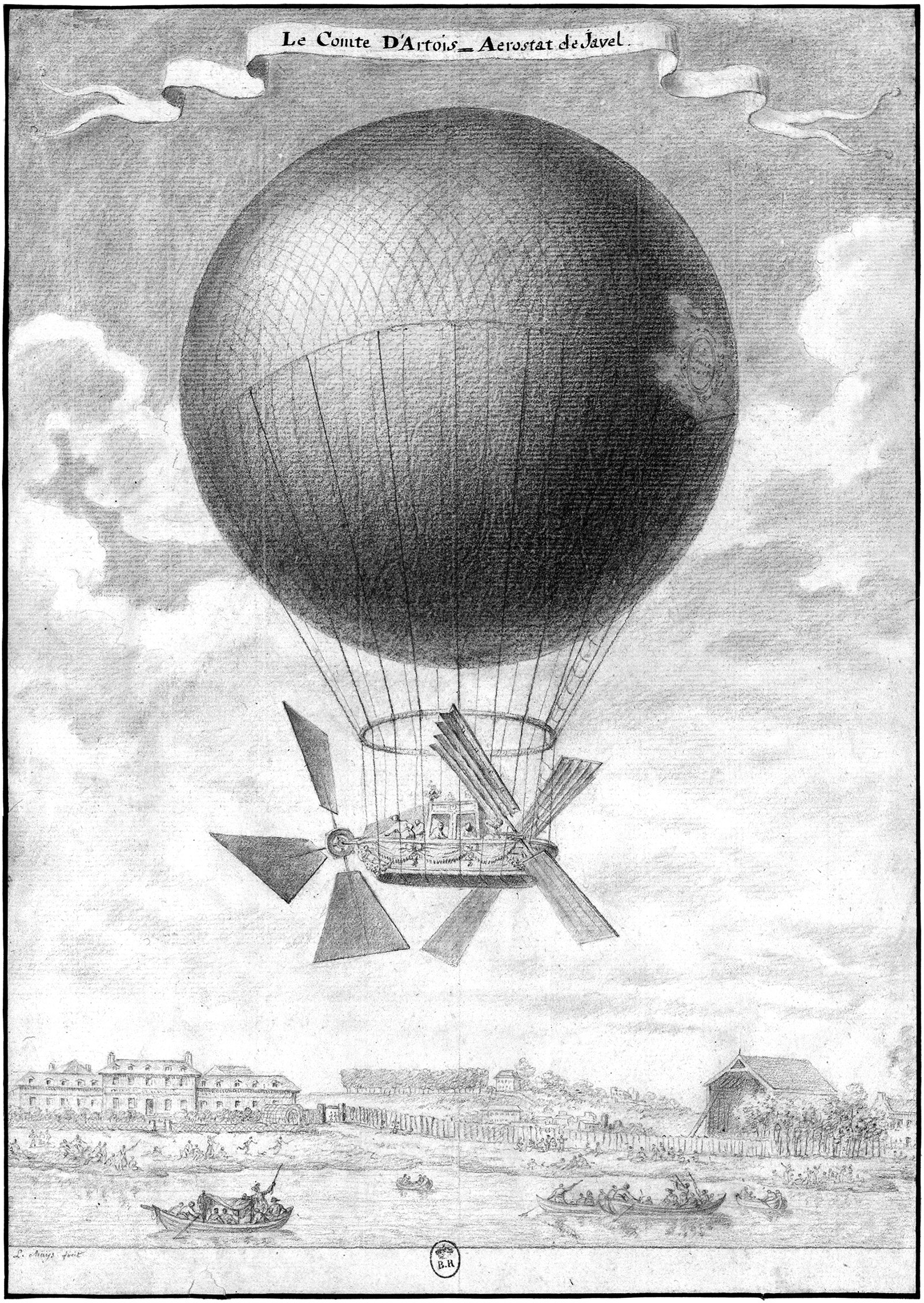

Alban & Vallet’s Comte d’Artois

Pictured above is a design for a flying machine by Léonard Alban and Mathieu Vallet from 1785. It was called Comte d-Artois, or l'Aérostat de Javel. It had a helium-filled balloon which carried a gondola. At one end of the gondola was a large propeller and at the other end was a pair of paddles. The gondola could comfortably seat four people and resembled a shallow boat. Throughout 1785, Alban and Vallet made many successful flights around Paris with the craft, and they also made three notable advancements in ballooning technology along the way.

“The airplane has unveiled for us the true face of the earth. For centuries, highways had been deceiving us. They shape themselves to man’s needs and run from stream to stream.”

-Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, French writer and aviator, 1900-1944.

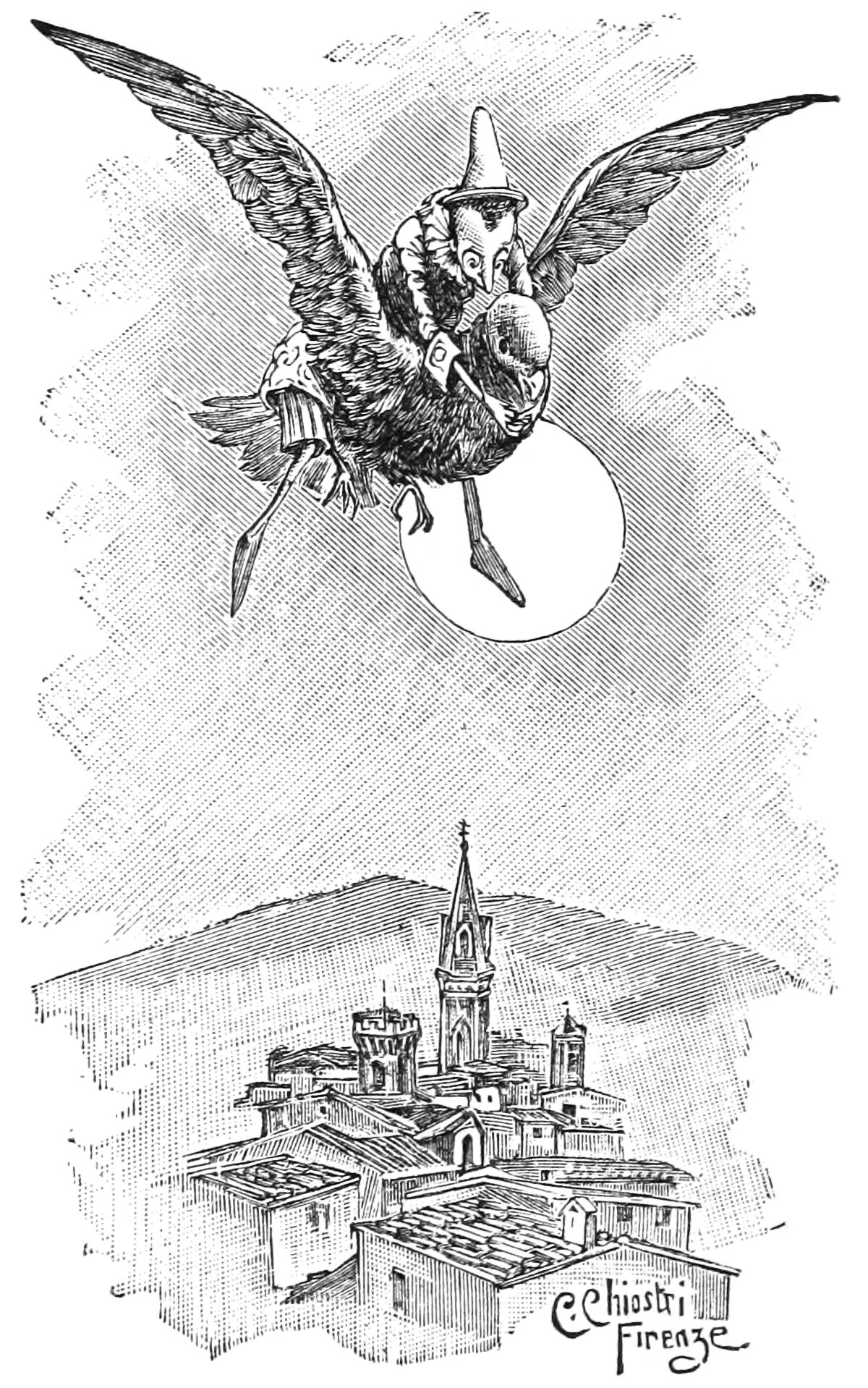

Pinocchio’s Feathered Steed

Folklore and fantasy are full of references to the power of flight. These references usually take one of two different forms. The first are characters who can actually fly, and the second are characters who fly by means of another creature. Examples of the first are fairies, angels, cherubs, and seraphs, among many others. The illustration above shows an example of the second. It’s from Carlo Collodi’s 1883 children’s book The Adventures of Pinocchio, when the titular character hitches a ride on the back of a giant pigeon.

Richard Pearse and a Claim to the World’s First Powered Flight

Pictured above is a photograph of a monoplane designed and built by Richard Pearse in 1903. Pearse was a farmer who had an interest in engineering, flight and flying machines. He had previously designed bicycles and engines, but in the early 1900s he was working on a design for a flying machine. It was a monoplane with a front-mounted propeller and a large wing constructed of a bamboo frame and canvas.

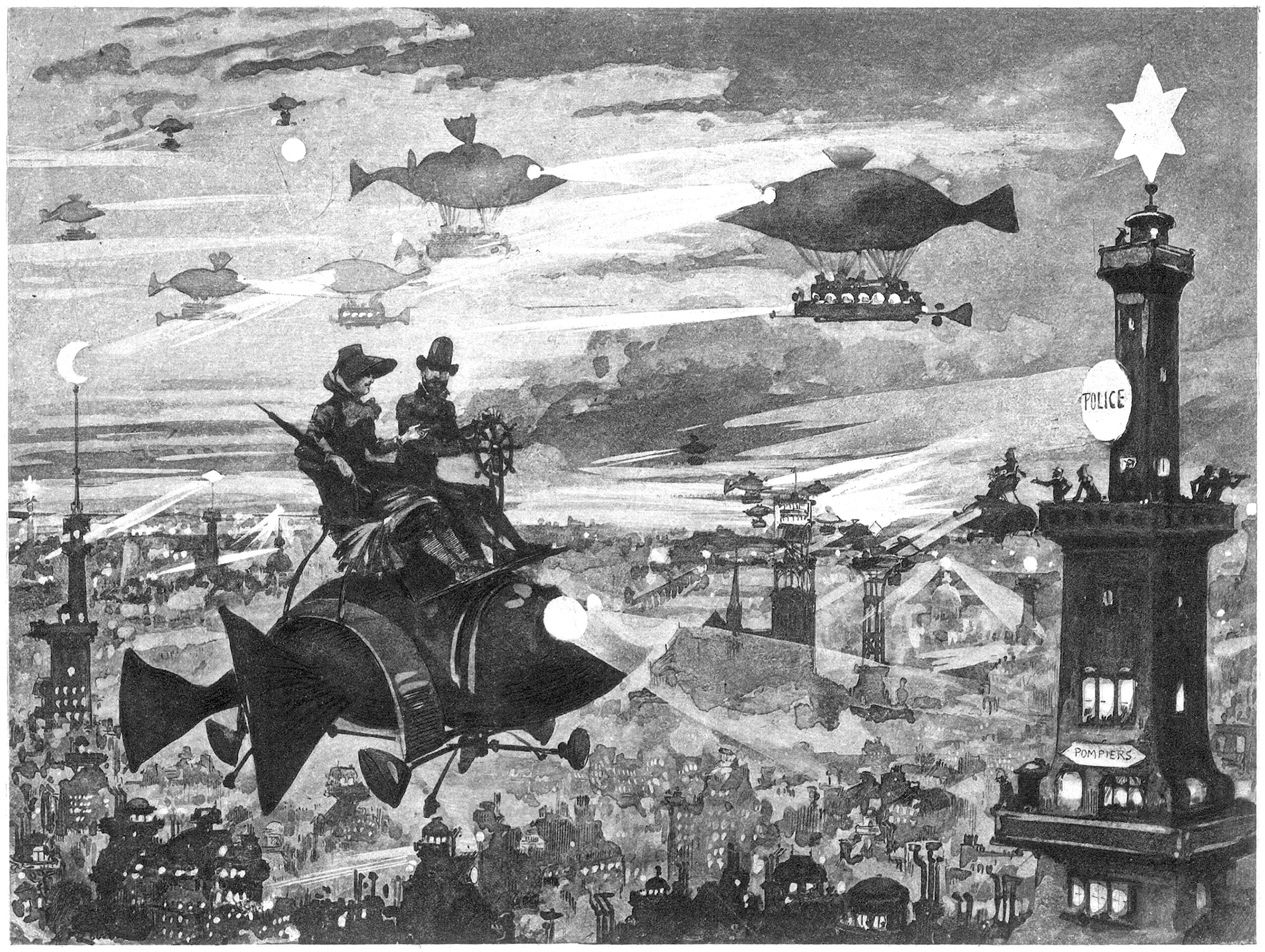

Albert Robida’s Vision for Paris

The above illustration was drawn by Albert Robida for his 1883 novel Le Vingtième Siècle, or The Twentieth Century. The novel describes a future vision for Paris in the 1950’s, focusing on technological advancements and how they would affect the daily lives of Parisians. Here he shows a vision for the night sky above Paris, which is dotted with various types of flying machines.