Welcome to On Verticality. This blog explores the innate human need to escape the surface of the earth, and our struggles to do so throughout history. If you’re new here, a good place to start is the Theory of Verticality section or the Introduction to Verticality. If you want to receive updates on what’s new with the blog, you can use the Subscribe page to sign up. Thanks for visiting!

Click to filter posts by the three main subjects for the blog : Architecture, Flight and Mountains.

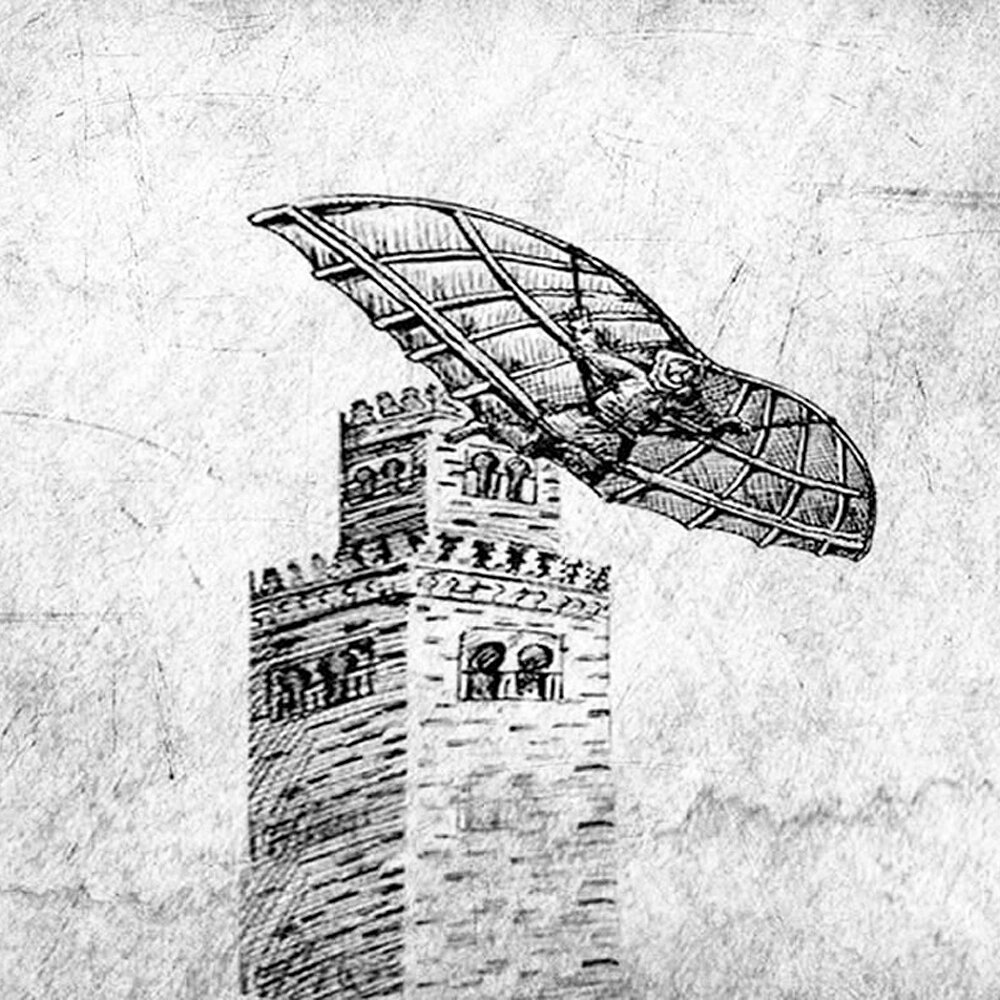

Tito Livio Burattini’s Flying Dragon

The above sketch is by Italian engineer Tito Livio Burattini, drawn sometime between 1647 and 1648. At first glance, it’s hard to reconcile a sketch of a flying dragon with a serious proposal for human flight, but Burattini had spent quite a bit of time researching flight, and the sketch was part of a larger treatise on the subject. It was titled Ars Volanti, and throughout the text Burattini wrestled with the idea of flight and how it may be achieved.

“It is impossible that men should be able to fly craftily by their own strength.”

-Giovanni Alfonso Borelli, Italian physiologist and mathematician, 1608-1679.

“A greater fear I do not think there was ... when I perceived myself on all sides in the air, and saw extinguished the sight of everything but the monster.”

-From The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri, Italian poet and philosopher, 1265-1321.

“Mechanical wings allow us to fly, but it is with our minds that we make the sky ours.”

-William Langewiesche, American journalist and aviator, born 1955.

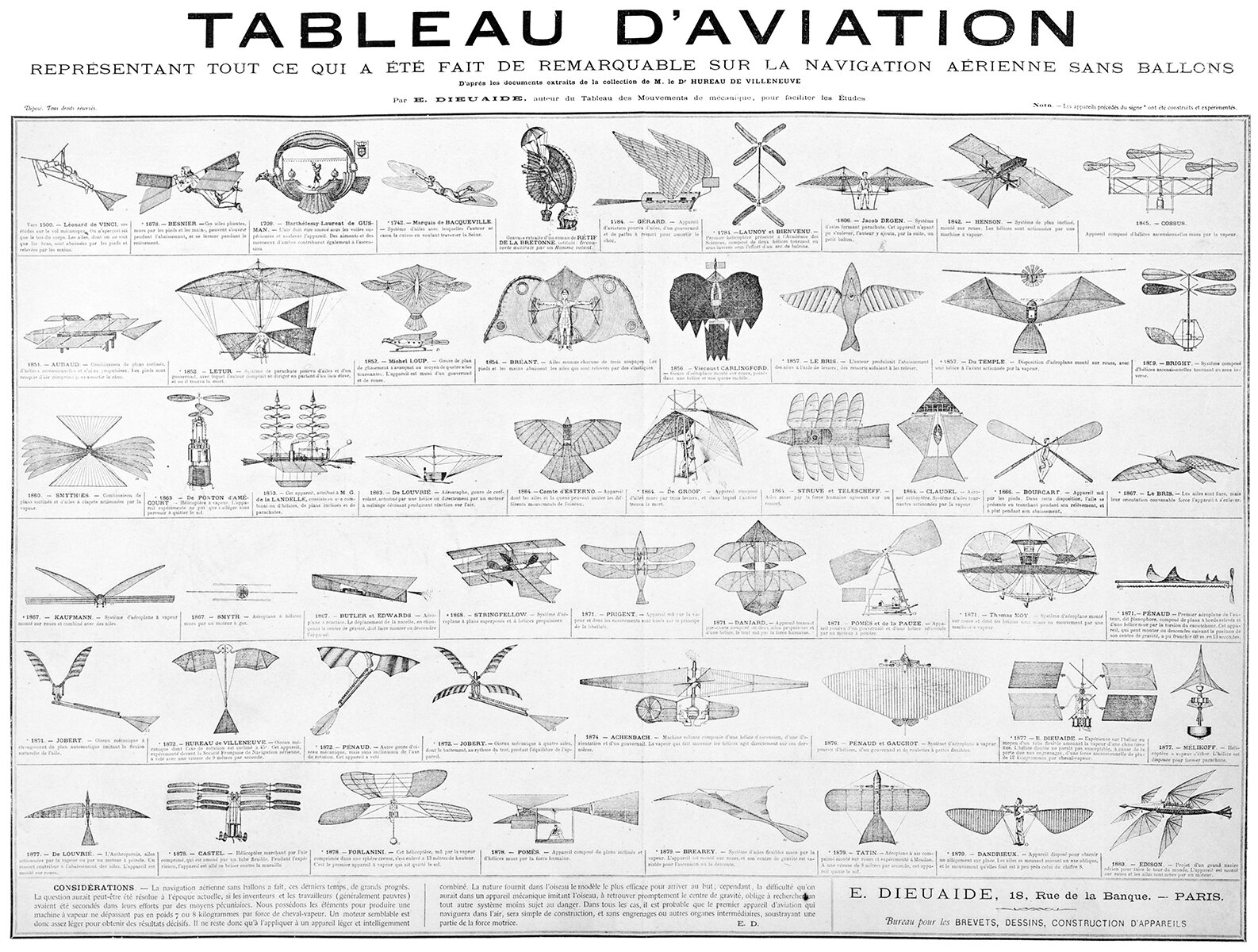

Tableau d’Aviation

The creativity and ingenuity on display throughout the history of flying machines is amazing. A quick survey of the table above shows the wide variety of ideas tried out before we humans successfully learned how to fly. One thing I love about this table is that it includes fictional flying machines as well as real prototypes. This shows that fictional designs can and have influenced the history of flight just as real prototypes have.

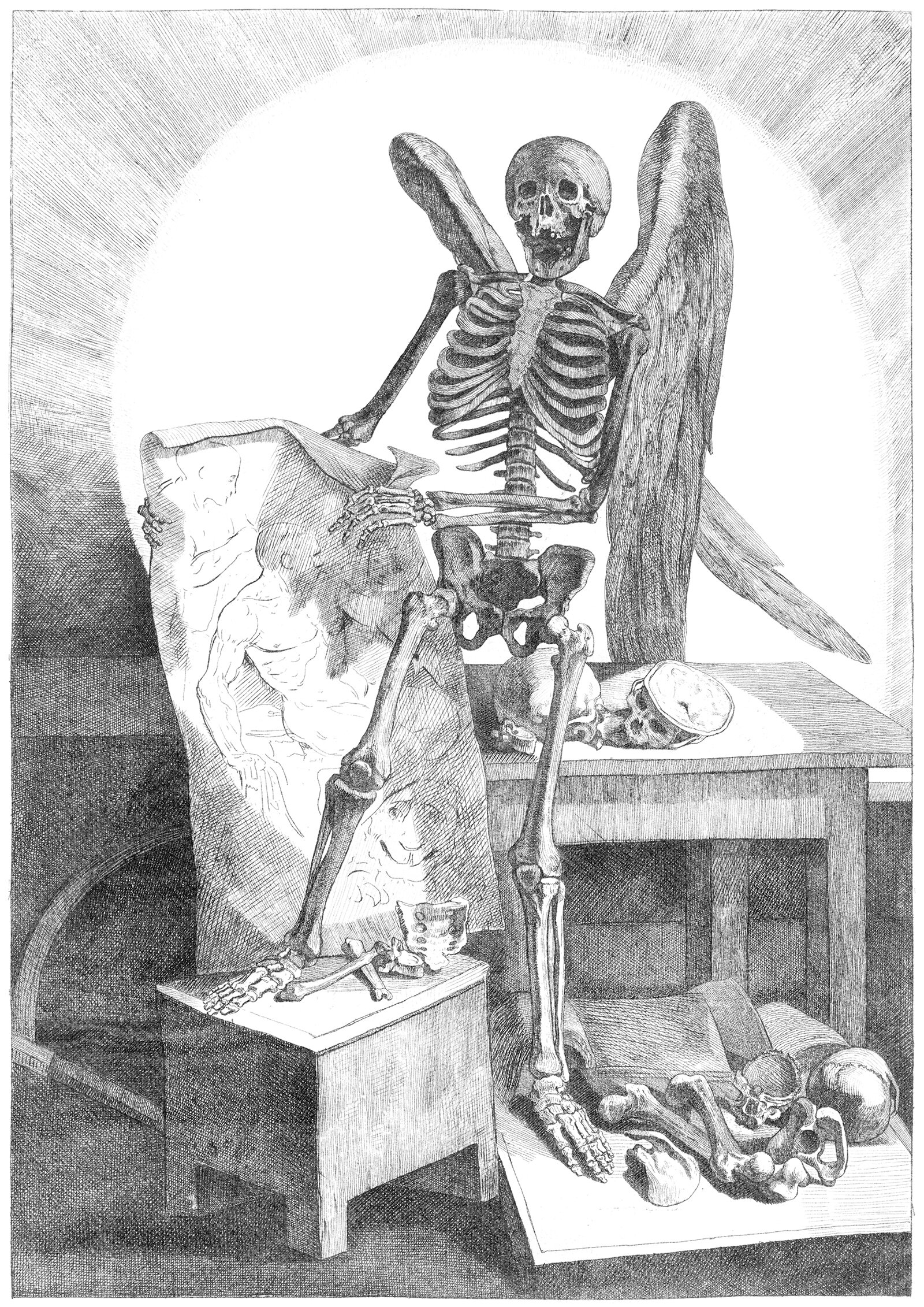

The Human Body and Flight : Why We Can’t Fly

The ability to fly is something that’s been on the human mind since time immemorial. We see birds and other creatures flying through the air, and we seek to fly as they do. We dream about it, and we’ve thought up myriad examples of human-like characters throughout our legends and myths who can fly. For all our hoping, however, it’s impossible for us to fly under our own strength. Let’s take a closer look at why this is true.

The Myth of Wayland the Smith

Throughout the history of myths and legends, there are myriad stories that are shared or borrowed from earlier sources, then re-named and adjusted for a different culture. Certain themes repeat themselves throughout the ancient world, and those that resonate most effectively will endure over time and evolve alongside the cultures they exist in. The myth of Wayland the Smith is one of these.

King Bladud and the Myth of the Flying Man

Legends have a way of expanding through time. They exist in the collective consciousness of the people who believe them, and the ones that endure usually grow and evolve alongside the cultures and civilizations they exist in. Take the myth of King Bladud, for example. Over time his story has expanded and endured. This is because he made an attempt to fly.

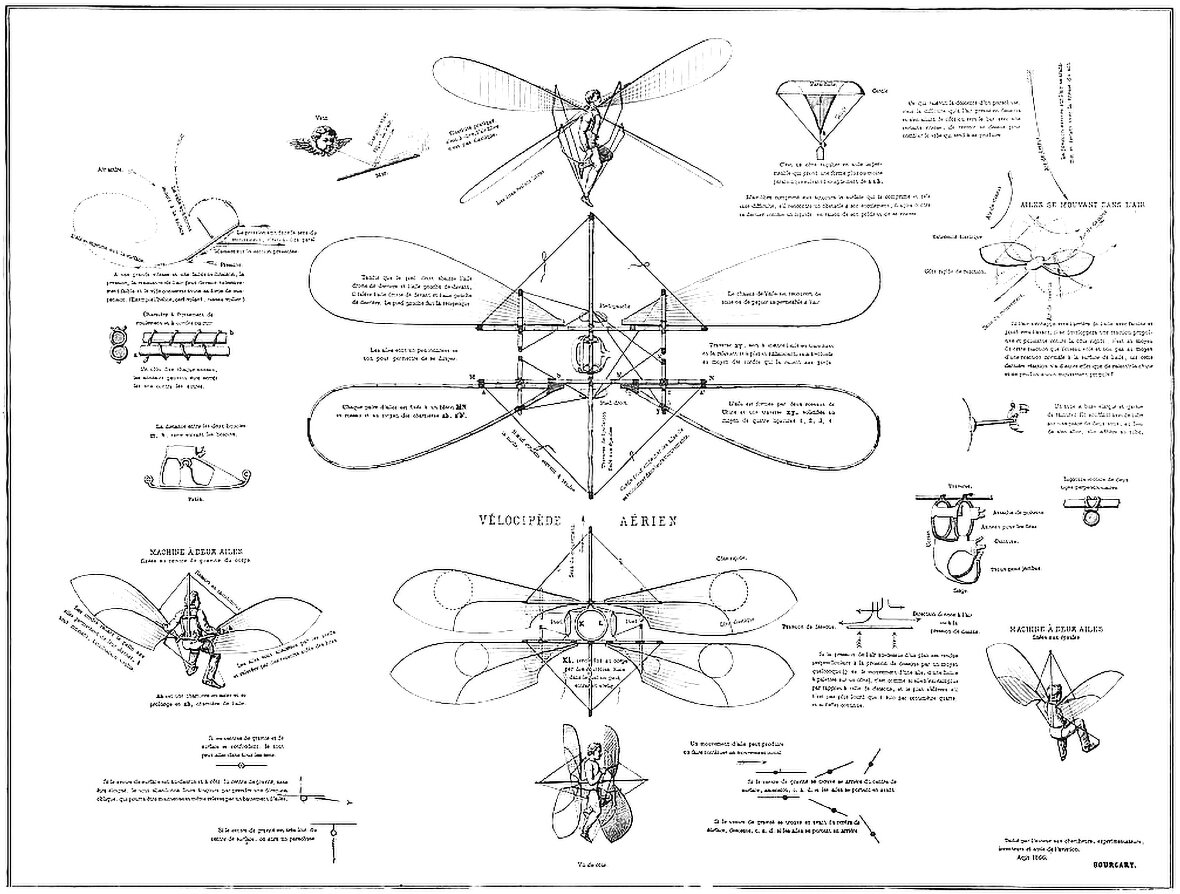

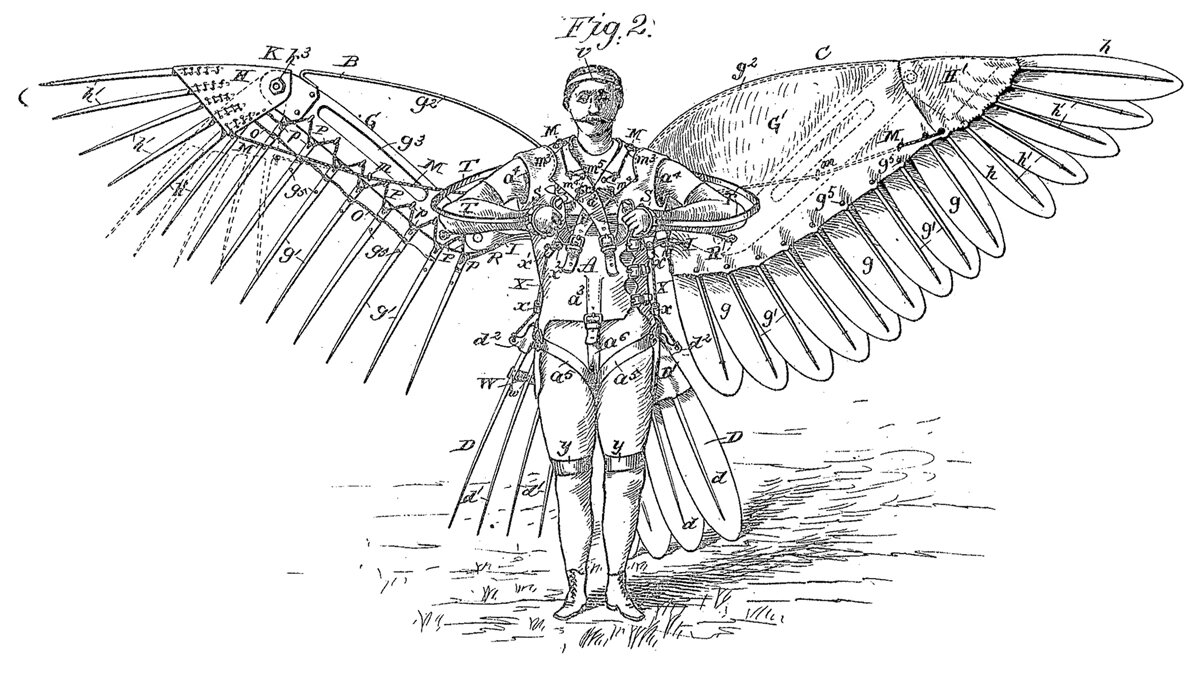

Jean Jacques Bourcart’s Ornithopter

Pictured above is a series of studies for a flying machine, proposed in 1866 by Jean Jacques Bourcart. Titled Vélocipède Aérien, the drawings show variations on an ornithopter design, in which a human pilot flaps the wings of the craft in order to fly. The subtitle of the illustration reveals that these are studies, tests and inventions which, without solving the problem of aviation, have nevertheless given interesting and encouraging results to the author.

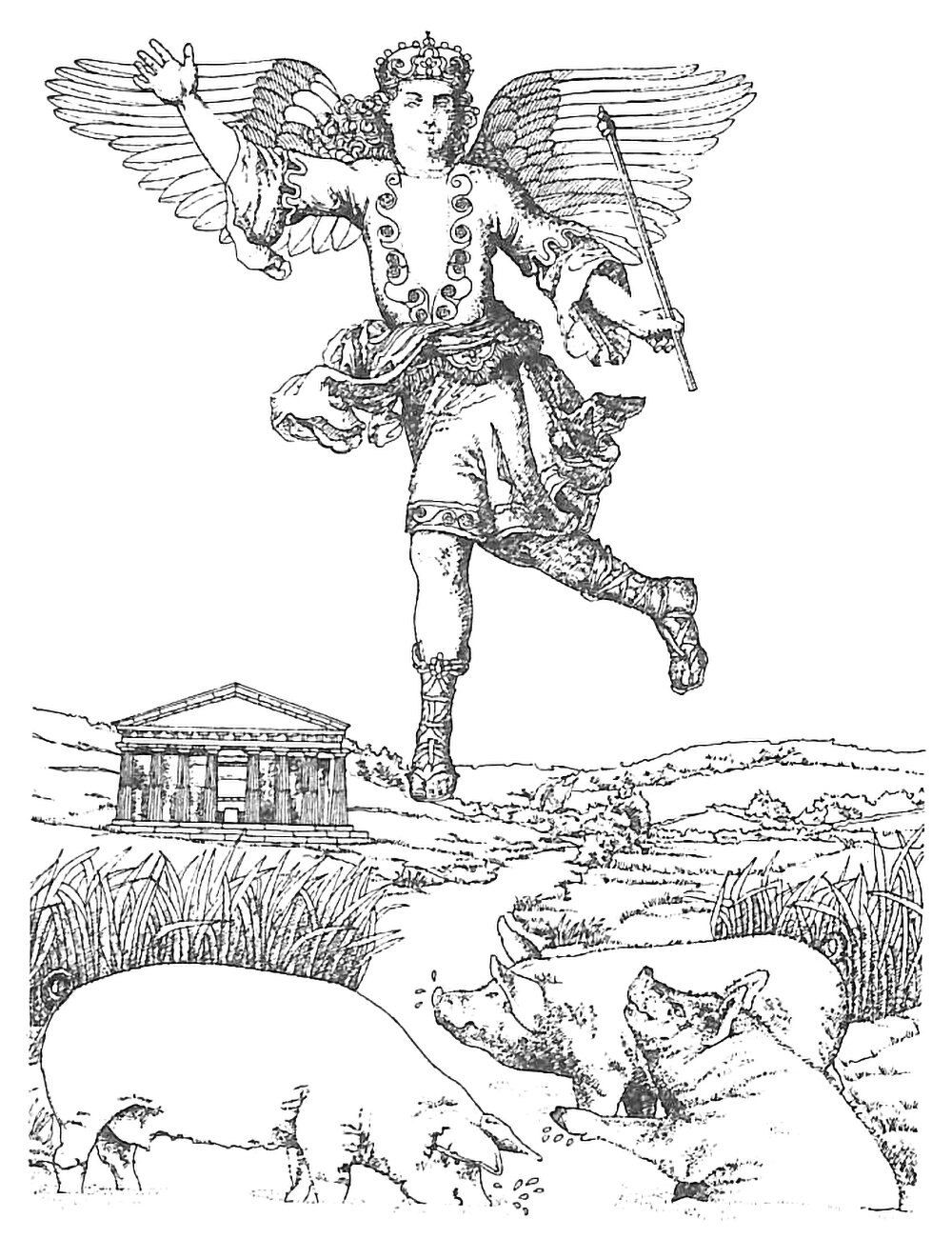

Daedalus and Icarus : A Parable of Human Flight

The oldest and most storied myth of human flight is the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Any history of flight, if tracked back far enough, will find it’s inception rooted in this timeless tale of youthful hubris. Over the centuries, the name Icarus has become synonymous with over-ambition, and has inspired countless other stories relating to human flight.

A Suggestion for a Flying Machine

The above illustration appeared in an 1877 issue of The Graphic, with the simple headline “A Suggestion for a Flying Machine”. Without any context or description, we can only take the image at face value. The machine seems to be lifted by a group of balloons placed centrally between two large wings, and the pilot dangles from a pole at the center of it all. Said pole has a tail behind it, and the pilot’s arms and legs control the tail and the wings, respectively.

‘We lack the wings to fly, but will always have the strength to fall.’

-Paul Claudel, French poet, 1868-1955

Abbas ibn Firnas’ Attempt At Flight

Abbas ibn Firnas, also known as Armen Firman, was an Andalusin polymath best known for an attempt at flight around 875 AD. Details are scarce, but Firnas allegedly built a pair of wings and jumped from a tower somewhere in Córdoba. His wings allowed him to glide for a bit before crash-landing and injuring his back.

R.J. Spalding’s Birdman Suit

This is Reuben Jasper Spalding’s design for a flying machine, which he successfully patented in 1889. The design is so on-the-nose, I haven’t made up my mind whether it’s amazing or absurd. There’s a chance it’s an honest attempt at human flight, but I see it more as an homage to the earliest flying machines, which took the myth of Daedalus and Icarus and ran with it.

John Damian de Falcuis, the False Friar of Tongland

Pictured above is John Damian, an Italian alchemist best known for an attempt at human flight in 1507. At the time, Damian had been employed by King James IV as an alchemist, and his job was to create gold from more common materials. After he failed to do so and word got around that he was a fraud, he declared he would fly to France with a pair of wings he invented in an attempt to prove his critics wrong,

“I’m learning to fly, but I ain’t got wings. Coming down is the hardest thing.”

-Tom Petty, American singer and songwriter, 1950-2017

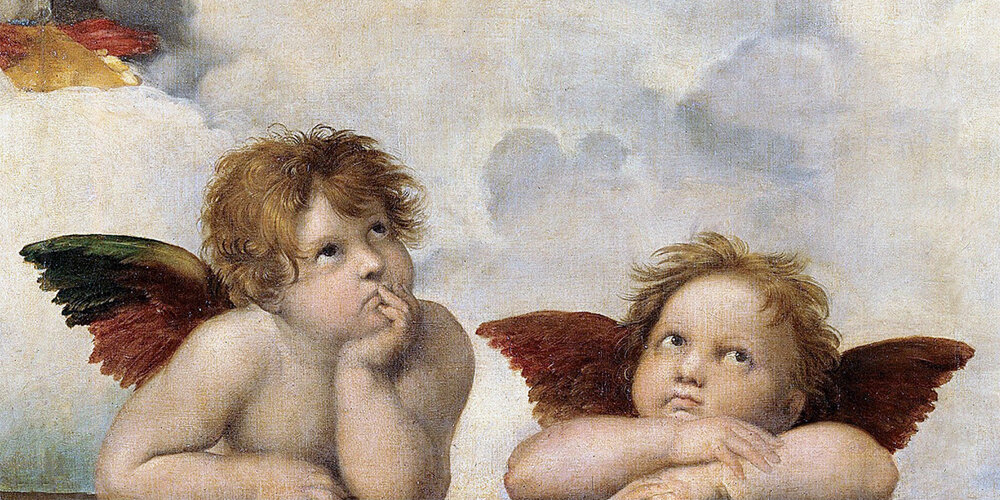

The Two Cherubs

For nearly all of human history, the space above our heads represented the unknown. Our ancestors would look up in awe, longing to satiate the innate need within us for Verticality. The two little cherubs pictured above encapsulate this innate need to escape the Earth’s surface, and their resulting fame apart from the painting they inhabit serves to illustrate this.

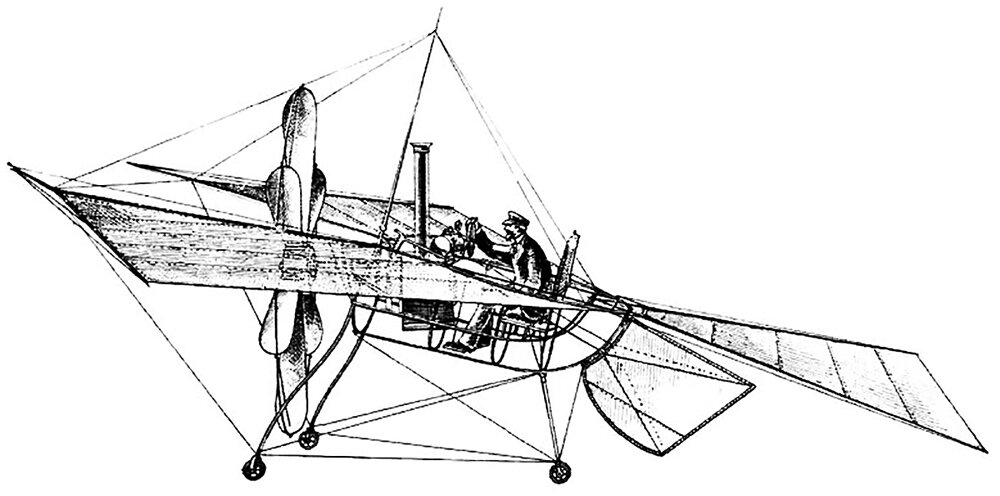

Félix du Temple’s Monoplane

Pictured above is an illustration of Félix du Temple’s design for a monoplane, which he and his brother Luis built and tested in 1874. One such test saw the machine take off from a ski-jump and glide for a bit before safely landing back on the ground. This flight, though short, gave the craft a claim to the first successful powered flight in history.

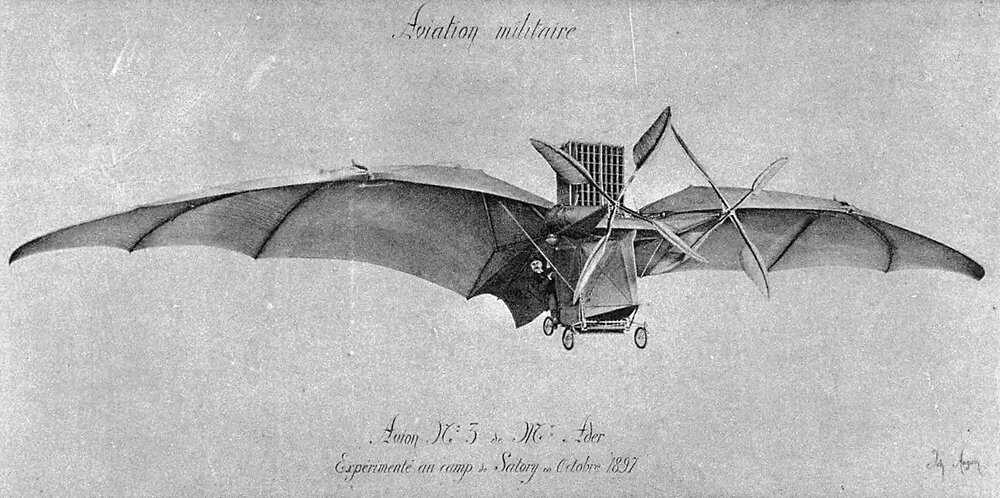

Clément Ader's Éole and Avion III

This is Avion III, an 1897 aircraft designed by Clément Ader. Ader was a French inventor and engineer, who became interested in flight after working on electrical communications and gas ballooning for much of his career. This was the second flying machine he designed. It was an updated and improved version of his first design from 1890, the Ader Éole.

Otto Lilienthal, The 'Flying Man'

I have yet to come across a history of flight that doesn’t include Otto Lilienthal. Known as the ‘Flying Man’, Lilienthal was a pioneer of aviation best known for his experiments with gliders and human flight. He made thousands of successful test flights throughout his career, and there are myriad photographs of him before and during these test flights. Pictured above is one such photo of him getting ready to make the leap off a hilltop.